Proust Was Goofing on Us

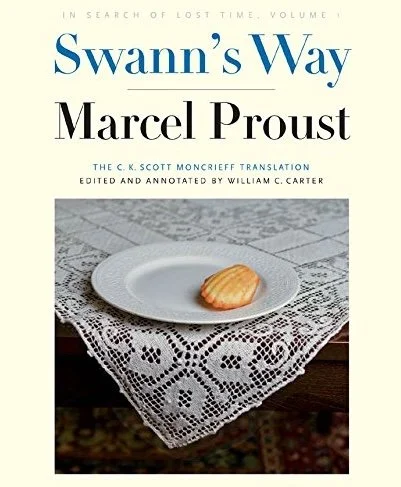

Proust goes on and on and on about a cookie, or madeleine, depicted here. Was his book one long joke?

HOBOKEN, JANUARY 29, 2026. You’re in a groovy jazz club, Dizzy’s, where a trumpet player dazzles you with his virtuosity. An hour in he pauses for breath, you start clapping with relief, now you can Uber home and watch Seinfeld. But with a wink this maniac keeps going—still brilliantly!—and shows no sign of stopping. Ever. Too much!

That’s how I’ve always felt when I tried to read Proust. Not bored so much as bullied. But after many false starts, I finally finished Swann’s Way, Moncrief translation. That’s just volume one of Proust’s seven-volume autofictional opus In Search of Lost Time. But that’s more than enough for me to get the joke.

Swann’s Way is impressive in its own oddball way, but I see it as a literary curiosity, like the bizarre, bawdy 18th-century novel Tristram Shandy. If you read Wikipedia on In Search of Lost Time, you’ll see that Proust’s fans tend to take him very seriously.

But Proust, I’ve decided, was goofing on us. Like Hawking when he predicted physics was on the verge of a “theory of everything” that would solve the riddle of the universe. Like psychedelic pundit Terence McKenna when he predicted shit’s gonna hit the fan in 2012. Evelyn Waugh parodied Swann’s Way, but the novel is its own parody.

Before I elaborate, some objective info on Proust’s sly ode to subjectivity: Originally published in French in 1913, the year before the Great War erupted, Swann’s Way has three parts, all narrated by a guy—call him Marcel--looking back at his youth.

In part one, Marcel recalls his childhood in the town of Combray, and he becomes obsessed with his parents’ mysterious friend Charles Swann. In part two, Marcel tells the tale of Swann’s obsessive love for Odette. In part 3, Marcel recounts his obsession with Gilberte, daughter of Swann and Odette.

To be clear: Swann, and obsession, are binding threads.

Proust’s style is often described as “stream of consciousness.” But I reserve that label for authors like Joyce and Woolf, who convey how it feels to be conscious at the moment of consciousness. Marcel is always remembering how it feels to be conscious.

Adult Marcel recalls what he saw, heard, smelled, tasted, felt as a boy. I gush about paying attention, even equating it with enlightenment. Proust takes paying attention to fetishistic extremes.

You’ve heard of the madeleine. Well, Marcel pays close attention to all sorts of odds and ends. Hawthorn bushes. Church steeples. A snippet of sonata. He fondles them in his mind, turning them this way and that, scrutinizing them from every possible angle, interminably.

Like Pynchon in Gravity’s Rainbow and Wallace in Infinite Jest, Proust flaunts his fecundity. The verbosity of all three authors has a subtext: I can rave about any arbitrary thing forever, because I’m a fucking genius!

But Gravity’s Rainbow and Infinite Jest are action-packed thrillers compared to Swann’s Way. Proust eschews plot for impressions. Even the most mundane, arbitrary thing serves as an emblem of everything. Yeah, I get that, but Proust pounds that mystical truism to death.

Sensory stimuli trigger epiphanies, mini-essays, on art versus nature, love versus desire, subjective versus objective reality, the interplay of perception, memory, emotion, imagination. If I had to sum up Proust’s philosophical outlook, it might be this: What is real? Who knows! Who cares! Let us dwell forever in our lovely, imagined pasts.

After all, the present is so drab. At the end of Swann’s Way, grownup Marcel reflects bitterly over how ugly Paris’ Bois de Boulogne has become. Women have traded their lovely 19th-century gowns for hideous 20th-century dresses, cars have replaced horse-drawn carriages. Ugh. Modern life sucks.

Proust excels at conveying gladsadness. Marcel’s boyish raptures are underpinned by his anticipation of loss. Beauty is so fleeting! But beneath the melancholy you see glints of irony. Proust keeps winking at us.

Example: In Part 1 of Swann’s Way, Proust depicts young Marcel as a comically sensitive little chap. He suffers when he thinks Mommy, who’s having a dinner party, won’t come up to his room to kiss him goodnight. Agony! Mommy comes after all. Ecstasy! But Marcel has torn Mommy from her guests. Guilt! Portrait of the Artist as a Momma’s Boy.

Later, the lad is riding through the country, and, overcome by the sublimity of village steeples (or is it the hawthorn blossoms? or both?), he bursts into song, startling the carriage driver. I chuckle picturing the grizzled driver squinting at this kid and thinking, What the…?

Another humorous incident: The boy visits a family friend, some old rich guy, who happens to be “receiving” a young woman, too. Well, the lady, it turns out, is shady. Marcel dutifully reports his observations to his parents, who thereafter shun the old horndog. So the mamma’s boy is also a tattle tale.

Marcel tattles on others, too. With faux innocence, he lays bare the pretension, hypocrisy, vapidity and cattiness of the bourgeois snobs who populate his world. They’re poseurs, phonies, especially when it comes to art. Culture is all about status- and virtue-signaling.

Worldly, wealthy Charles Swann seems the exception, at first. In part 1 of Swann’s Way, Swann comes across as intelligent, modest, kind, elegant, a man with superb taste. But in part 2, once again narrated by Marcel looking back, Swann falls for Odette de Crécy and turns into an idiot.

Everyone knows Odette is a high-class hooker. Swann knows too, he just denies what his own eyes tell him. No fool like a fool in love. I felt pangs of recognition reading Proust’s merciless exposé of male infatuation. But I found “Swann in Love” hilarious, too.

Proust devoted his life to telling the longest joke ever—more than 3,000 pages long--and passing it off as a masterpiece. Improbably, his stunt worked. Self-anointed canon-keeper Harold Bloom proclaimed In Search of Lost Time “the major novel of the 20th century.” Um, no, that would be Ulysses.

Proust’s reputation demonstrates our vulnerability to the sunk-cost fallacy. The more you read of Lost Time, the more you need to convince yourself your time hasn’t been wasted. Lost! If you finish all seven volumes you’re compelled to proclaim: Best novel ever! This same logic keeps string theory and other failed projects going.

I have no desire to read another volume of Lost Time, let alone all seven. But I don’t regret reading Swann’s Way. I understand now why many readers love Proust. He has forced me to reflect on what I want from literature.

What I don’t want, I realize, at this particular historical moment, is an amoral, aesthetic take on life, which prioritizes impressions over plot, subjectivity over objectivity. We’re debating whether killings committed by government agents are murder or self-defense. There is an answer, and it matters.

Let me double down on my moralizing: What I don’t want, in the MAGA era, is literature that celebrates, even ironically, fondness for an imagined past. Delusional nostalgia, when it becomes state ideology, isn’t funny. It’s terrifying.

Further Reading:

For more riffs on literature, see Pynchon, Thanatoids and the Ferris Wheel of Life, Is “The Waste Land” Accurate?, What’s Poetry’s Point? A Riff on “Paterson”, Solzhenitsyn, the Gulag and Free Will, Surfing Woolf’s “The Waves”, Woolf Versus Buddha, I Read Gravity’s Rainbow So You Don’t Have To, Is David Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest” Really, Like, Great?, My Bloomsday Tribute to James Joyce, Greatest Mind-Scientist Ever, Henry James, The Ambassadors and the Dithering Hero, The Golden Bowl and the Combinatorial Explosion of Theories of Mind, Free Will, War and the Tolstoy Paradox, Moby Dick and Hawking’s “Ultimate Theory”, Jack London, Liberal Arts and the Dream of Total Knowledge.