Murray Gell-Mann and “The End of Science”

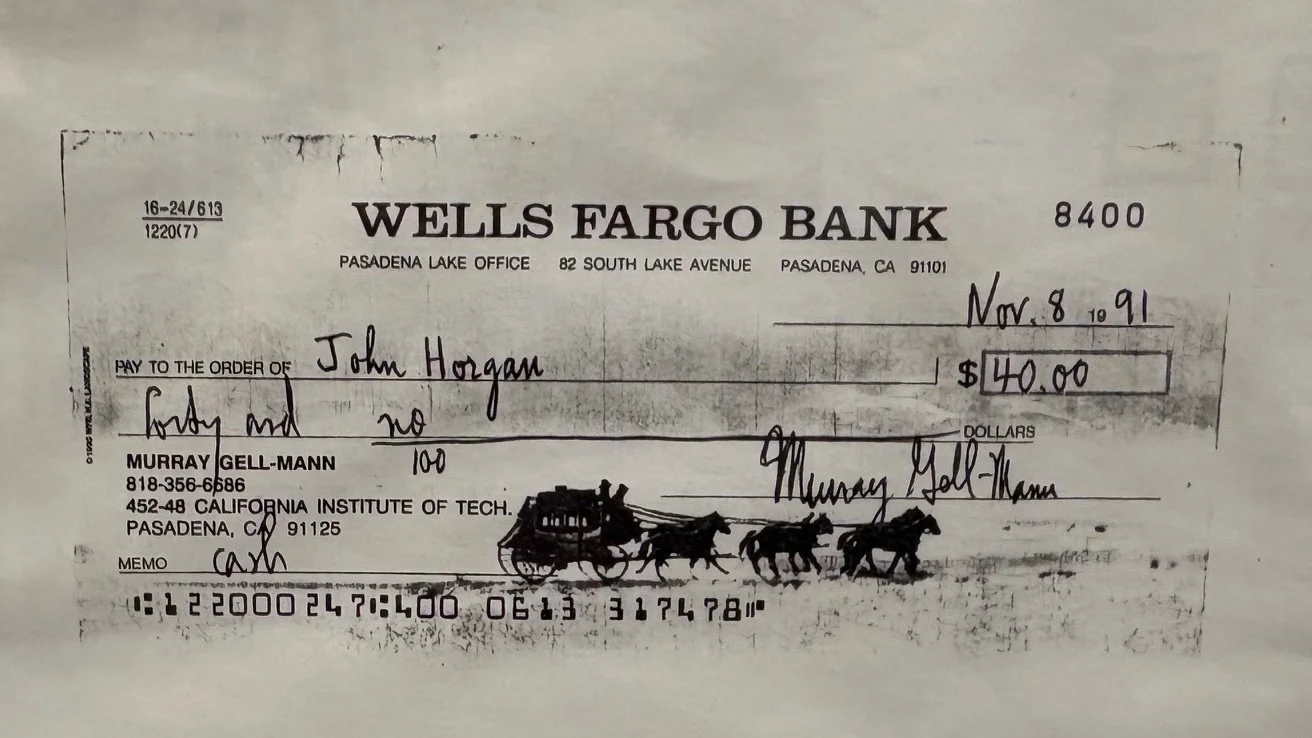

Gell-Mann wrote me this check in 1991. See end of this column for the story behind the check.

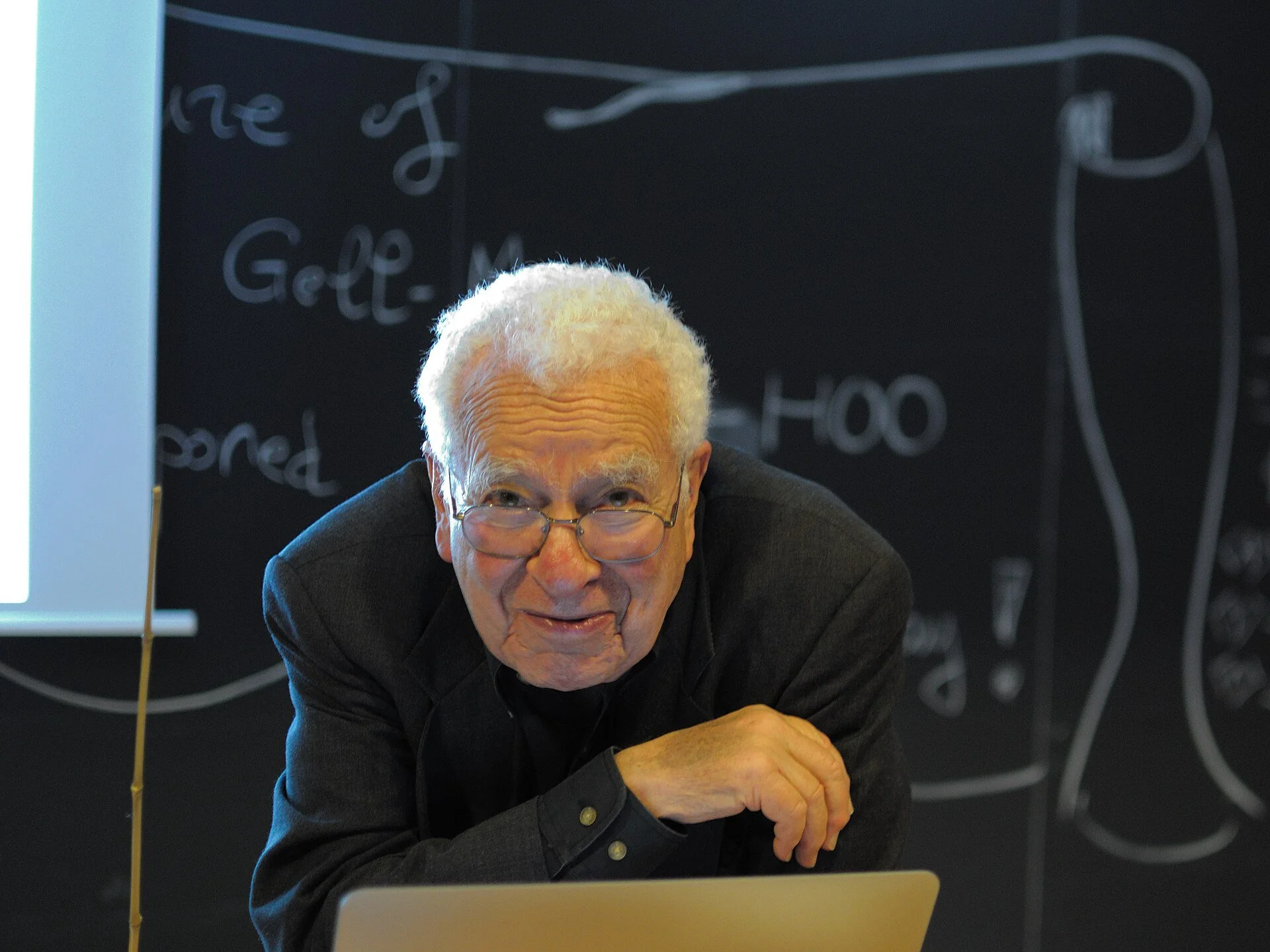

HOBOKEN, FEBRUARY 3, 2026. Murray Gell-Mann (1929-2019) was a diminutive titan of 20th century physics. I interviewed him twice: in 1991, for a Scientific American profile; and in 1995, for an article on complexity research. In my 1996 book The End of Science, I cited Gell-Mann to advance my thesis that science is bumping into limits. Gell-Mann was not amused. He said I should get an Ig Nobel Award for my "ridiculous theory that science is mined out." And yet Gell-Mann himself… Well, read this edited excerpt from The End of Science and judge for yourself. -- John Horgan

Murray Gell-Mann excels at reducing complexity to simplicity. He won a Nobel Prize in 1969 for finding a unifying order beneath alarmingly diverse particles streaming from accelerators. He called his particle-classification system the Eight-fold way, after the Buddhist path to wisdom. (The label was a joke, he emphasized, he’s not one of these flakes who thinks physics and Eastern mysticism have something in common.)

Gell-Mann showed the same flair for reductionism when he proposed that neutrons, protons and other shorter-lived particles consist of triplets of “quarks” bound together by a “strong” nuclear force. Quark theory, a.k.a. quantum chromodynamics, has been corroborated in accelerators and is now a cornerstone of the standard model of particle physics.

Gell-Mann likes recalling how he came up with the term “quark” while perusing James Joyce’s gobbledygookian masterpiece Finnegans Wake. (The passage reads, “Three quarks for Muster Mark!”) This anecdote serves notice that Gell-Mann’s intellect is far too capacious to be satisfied by physics alone.

According to a “personal statement” that he distributes to reporters, Gell-Mann’s interests encompass not only physics and literature but also nuclear arm-control, history (natural and human), population growth, sustainable development, archaeology and linguistics. Gell-Mann has some familiarity with all the world's major languages, and he enjoys informing people about the etymology and correct native pronunciation of their names.

Gell-Mann’s literary agent, John Brockman, says Gell-Mann “has five brains, and every one is smarter than yours.” Gell-Mann is unquestionably one of the world’s most brilliant scientists. He is also one of the most annoying, because of his fondness for touting his own talents and belittling others’.

Gell-Mann displayed this trait when we met in 1991 in a New York City restaurant. I had barely sat down when Gell-Mann began telling me—as I set out my tape recorder and yellow pad—that science writers are “ignoramuses” and a “terrible breed” who invariably get things wrong; only scientists are qualified to present their work to the masses.

As time went on, I felt less offended, since Gell-Mann obviously held many of his scientific peers in contempt as well. After a series of demeaning comments about other physicists, Gell-Mann said, “I don't want to be quoted insulting people. It's not nice. Some of these people are my friends.” [See Addendum for a story about how this meeting ended.]

I interviewed Gell-Mann again in 1995 at the Santa Fe Institute, a small but influential research center dedicated to the study of complex systems. Gell-Mann was one of the first prominent scientists to climb aboard the complexity bandwagon. He helped found the Santa Fe Institute and became its first full-time professor in 1993, after decades at Caltech.

In his 1994 book The Quark and the Jaguar, Gell-Mann lays out his hierarchical view of science. At the top are theories that apply everywhere in the known universe, such as the second law of thermodynamics and his own quark model. Other theories, such as those related to evolution and genetics, apply only here on earth, and phenomena they describe entail randomness and historical circumstance.

“With biological evolution we see a gigantic amount of history enters,” he told me, “huge numbers of accidents that could have gone different ways and produced different life forms than we have on the earth, constrained of course by selection pressures. Then we get to human beings, and the characteristics of human beings are determined by huge amounts of history. But still, there's clear determination from the fundamental laws and from history, or fundamental laws and specific circumstances.”

Gell-Mann's reductionist predilections can be seen in his attempts to substitute his own neologism, plectics, for complexity. Plectics “is based on the Indo-European word plec, which is the basis of both simplicity and complexity,” he said. “So in plectics we try to understand the relation between the simple and the complex, and in particular how we get from the simple fundamental laws that govern the behavior of all matter to the complex fabric that we see around us.” (Unlike quark, plectics has not caught on. I have never heard anyone besides Gell-Mann use the term—except to deride Gell-Mann's fondness for it.)

I asked if Gell-Mann agreed with what his Santa Fe colleague and fellow Nobel laureate Phil Anderson said in his influential 1972 essay "More Is Different.” “I have no idea what he said,” Gell-Mann replied disdainfully. (Gell-Mann liked to call Anderson’s field “squalid-state physics.”) I explained Anderson's idea that complex phenomena such as life and consciousness require their own theories; you cannot reduce them to physics.

“You can! You can!” Gell-Mann cried. “Did you read what I wrote about this? I devoted two or three chapters [of Quark and Jaguar] to this!” Biological phenomena, he acknowledged, cannot be easily deduced from fundamental physical principles, but that does not mean organisms are ruled by their own laws operating independently of the laws of physics. “I founded a whole institute to try to react against excessive reductionism,” Gell-Mann said, “but reductionism in principle hasn't been proved wrong.”

Gell-Mann rejected the possibility--raised by his Santa Fe colleague Stuart Kauffman and others--that there might be a still-undiscovered force of nature that organizes matter into ever-more complex forms in spite of the inexorable increase of entropy. This issue, too, is settled, Gell-Mann said. The universe began in a “wound-up” state far from thermal equilibrium. As it winds down, disorder increases, on average, throughout the system, but there can be local violations of that tendency.

“It's a tendency, and there are lots and lot of eddies in that process,” he said. “That's very different from saying complexity increases. The envelope of complexity grows, expands. It's obvious from these other considerations it doesn't need another new law, however!”

The universe creates “frozen accidents”--stars, galaxies, planets, stones, trees, humans--complex structures that serve as foundations for the emergence of still more complex structures. “As a general rule, more complex life forms emerge, more complex computer programs, more complex astronomical objects emerge in the course of non-adaptive stellar and galactic evolution and so on. But! If we look very, very, very far into the future, maybe it won't be true anymore!”

Eons from now the era of complexity could end, and the universe could degenerate into “photons and neutrinos and junk like that and not a lot of individuality.” Ah, yes, heat death, our ultimate fate.

“What I'm trying to oppose is a certain tendency toward obscurantism and mystification,” Gell-Mann continued. He emphasized that there is still much to be understood about complex systems. “There's a huge amount of wonderful research going on. What I say is that there is no evidence that we need some--I don't know how else to say it--something else!”

When he said “something else,” Gell-Mann wore a huge sardonic grin, as if he could scarcely contain his amusement at the foolishness of those who might disagree with him. He noted that “the last refuge of the obscurantists and mystifiers is self-awareness, consciousness.” Humans are obviously more intelligent and self-aware than other animals, but they are not qualitatively different.

“Again, it’s a phenomenon that appears at a certain level of complexity and presumably is emergent from the fundamental laws plus an awful lot of historical circumstances. Roger Penrose has written two foolish books based on the long-discredited fallacy that Gōdel's theorem has something to do with consciousness requiring”--pause—"something else.”

Particle physics, Gell-Mann said, still represents science's best hope of discovering profound new principles of nature. Gell-Mann believed string theory would probably be confirmed as the unified theory of all fundamental forces early in the next millennium.

But would such a far-fetched theory--with its extra dimensions and infinitesimal stringy particles--ever really be accepted? After I asked this question, Gell-Mann stared at me, as if I’d just confessed to belief in angels.

“You're looking at science in this weird way, as if it were a matter of an opinion poll,” Gell-Mann said. “The world is a certain way, and opinion polls have nothing to do with it! They do exert pressures on the scientific enterprise, but the ultimate selection pressure comes from comparison with the world.” He urged me to ignore “crazy criticisms” of string theory.

Gell-Mann also had no problem with theories that posit the existence of other universes; in fact, he is a proponent of the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. The goal of physics, he said, should be to determine whether our particular cosmos is probable or improbable.

“If it turns out that we’re in a very improbable universe,” Gell-Mann admitted, “it'll look funny.” But physicists can always fall back on the anthropic principle, he said, to explain why we happen to find ourselves in this particular universe.

Is science finite or infinite? For once, Gell-Mann did not have a pre-packaged answer. “That's a very difficult question,” he replied soberly. “I can't say.” His view of how complexity emerges from fundamental laws, he said, “still leaves open the question of whether the whole scientific enterprise is open-ended. After all, the scientific enterprise can also concern itself with all sorts of details.”

Details.

One reason why Gell-Mann is so insufferable is that he is almost always right. His assertion that research on complex systems will not yield something else—a profound new principle of nature—will probably prove to be correct. Gell-Mann errs—dare one say it?—only in his judgment of string theory. Unlike quarks, strings will never be empirically validated. Scientists will always have plenty of “details” to explore, but they will never again discover anything as fundamental as, say, quarks.

That sounds to me like the end of science.

Addendum: After our meal together in New York in 1991, I hired a limousine to take Gell-Mann and me to the airport, where he was catching a plane to California. He fretted that he did not have enough money to take a taxi home after his plane landed; if I could give him $40 in cash, he'd write me a check. Gell-Mann suggested that I not cash the check, since his signature would probably be quite valuable. I cashed the check but kept a photocopy, which I framed and put on display in my office.

Further Reading:

I’ve posted lots of columns related to this one here on “Cross-Check,” including The End of Physics?, The Chaoplexity Delusion, Mitchell Feigenbaum and the End of Chaoplexity, Huge Study Confirms Science Ending! (Sort Of), The Delusion of Scientific Omniscience, Pluralism: Beyond the One and Only Truth, and My Doubts about The End of Science.

See also the 2015 edition of The End of Science, my free online book My Quantum Experiment and my profile of chaoplexologist Stuart Kauffman in Mind-Body Problems.