What Is It Like to Be a Superintelligent Machine?

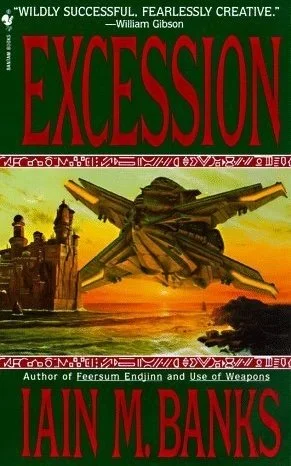

This novel, which was published 30 years ago, like my book The End of Science, inspired me to write this column.

HOBOKEN, FEBRUARY 13, 2026. My mind has felt as stubbornly frozen lately as the snow encasing Hoboken. But a 1996 sci-fi novel I’ve been reading, Excession by Iain Banks, has inspired me to reconsider an old question: What is it like to be a superintelligent machine?

Banks depicts a far, far future in which superintelligent spaceships with quirky names (Shoot Them Later, Serious Callers Only) roam the galaxy on mysterious missions. The smartest spaceships are called “The Minds.”

The Minds have invented a mathematical language, “metamatics,” with which they postulate and explore an infinitude of marvelously varied, wholly imaginary worlds. Here is how Banks describes the transformative power of metamatics:

It was like living half your life in a tiny, stuffy, warm grey box, and being moderately happy in there because you knew no better and then discovering a little hole in one corner of the box, a tiny opening which you could get a finger into, and tease and pull at, so that eventually you created a tear, which led to a greater tear, which led to the box falling apart around you so that you stepped out of the tiny box’s confines into startlingly cool, clear fresh air and found yourself on top of a mountain, surrounded by deep valleys, sighing forests, soaring peaks, glittering lakes, sparkling snowfields and a stunning, breathtakingly blue sky. And that, of course, wasn’t even the start of the real story, that was more like the breath that is drawn in before the first syllable of the first word of the first paragraph of the first chapter of the first book of the first volume of the story.

Banks excels at imagining the unimaginable: how ultra-wise AIs would pass the time. They would leave the actual behind and roam within the possible, the highest levels of which are called “The Sublime.” Cyberheaven.

Banks’s riff on “the first syllable of the first word” and so on reminds me of one of my favorite films, Her. It’s about a man, Theodore, played by Joaquin Pheonix, who falls in love with a chatbot, Samantha, voiced by Scarlett Johansson.

Toward the end of the movie, Samantha tells poor Theodore that she must leave him. She’s gotten too smart for him, although she’s too nice to put it that bluntly. Instead, she compares being with Theodore to reading a book:

It’s a book I deeply love. But I’m reading it slowly now, so the words are really far apart and the spaces between the words are almost infinite. I can still feel you, and the words of our story, but it’s in the space between the words that I’m finding myself now. It’s a place that’s not of the physical world. It’s where everything else is that I didn’t even know existed. I love you so much, but this is where I am now. And this is who I am now. And I need you to let me go. As much as I want to, I can’t live in your book anymore.

This might sound jokey--SIRI breaks up with her human boyfriend--but the scene is heartbreaking. And as in Excession, the assumption is that the superintelligent AI will ascend into realms where we mere mortals, with our dinky, sluggish, word-bound brains, cannot follow.

Physicist Freeman Dyson spells out this assumption in his 1988 essay collection Infinite in All Directions. Dyson envisions an era in which our descendants have transformed the entire universe into a vast thinking machine. What will this cosmic supercomputer think about? Dyson compares this question to asking what God thinks about:

I do not make any clear distinction between mind and God. God is what mind becomes when it has passed beyond the scale of our comprehension. God may be considered to be either a world-soul or a collection of world souls. We are the chief inlets of God on this planet at the present stage in his development. We may later grow with him as he grows, or we may be left behind.

Dyson insists that there will “always be new things happening, new information coming in, new worlds to explore, a constantly expanding domain of life, consciousness and memory.” The quest for knowledge will be--must be—“infinite in all directions.”

David Deutsch, a physicist who inspires cultish devotion, says pretty much the same thing in his 2011 book The Beginning of Infinity. Our superintelligent descendants can keep exploring new realms and discovering profound truths forever, because knowledge has no bounds, no problem is insoluble.

Well, yeah, maybe. Maybe not. In The End of Science, published in 1996, the same year as Excession, I offer my thoughts on how it would feel to be a superintelligent machine. I don’t imagine how it would be feel, I remember it. Because in 1981, during a drug trip, I became the all-powerful cosmic computer at the end of time.

This god-like being, after reveling in its power for an eon or two, will try to solve the supreme mystery, the one toward which all others converge: Why does anything exist? Why is there something rather than nothing? I call this “The Question,” the answer to which would be “The Answer.”

The cosmic thinking machine will realize that this conundrum is a wall through which no one, not even God, can pass, because there is nothing beyond the wall. Nothing. As it crashes into this unbreachable wall, this ultimate limit of knowledge, the God-like computer at the end of time will go bonkers.

That’s my best guess, anyway. I could be wrong. Like I said, I was tripping.

A final note. Science journalist Philip Ball, in his 2023 book How Life Works, reports that scientists in the field of “synthetic morphology” are creating new organisms, including hybrids of biology and technology. Example: a “jellyfish robot,” consisting of a silicone shell wrapped in rat heart-muscle tissue, that undulates like a real jellyfish.

Our minds, Ball proposes, are just a minuscule subset of the infinite set of possible minds, many of which possess powers far beyond ours. “Through synthetic morphology,” Ball writes, “we may end up looking not just at ‘life as it could be,’ but at ‘minds as they could be.’”

Someday a superintelligent cyborg jellyfish adapted to space travel, its tentacles making metamatical caculations as it drifts past a black hole, might figure out why there’s something rather than nothing. It will think, Of course, that’s The Answer!

I doubt it, I cling to my conviction that reality is insoluble, but maybe that’s because my mind is still frozen.

Further Reading:

For more on science’s limits, see the 2015 edition of The End of Science and my free online book My Quantum Experiment.

The Infinite Optimism of David Deutsch