What’s Poetry’s Point? A Riff on “Paterson”

I’ve been carrying this book around forever, but I only read the whole thing recently.

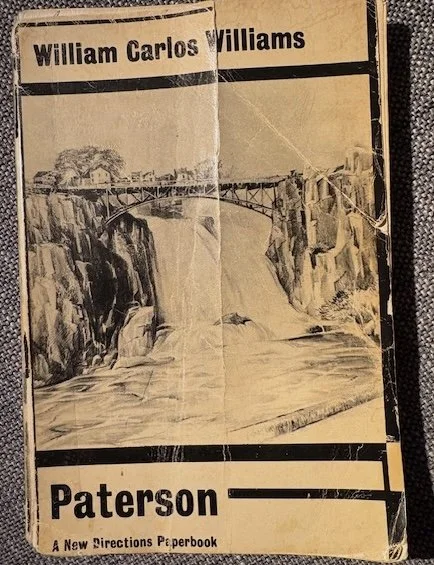

HOBOKEN, AUGUST 29, 2025. I’m not sure how or when I acquired Paterson, the 284-page anti-epic prose-poem by William Carlos Williams. My paperback copy, published by New Directions in 1963, is beat-up, weathered, its spine taped.

Maybe I stole Paterson from my sister Wendy when she brought it home from college a half century ago. Maybe Wendy scribbled these terse marginalia-- “Wasteland,” “Pound,” “money,” “sex,” “negation”--in delicate, maroon-tinted cursive throughout the book.

I’ve dipped into Paterson before. I quote Williams’s self-contradicting koan, “No ideas but in things,” in Mind-Body Problems. My conceit, I say, is “no ideas but in people.” Because, like, if there are no people, there are no ideas. Ideas don’t float free, right?

Only this month did I read Paterson from start to finish. I was feeling adrift, in need of purpose, a project, something to distract me from the shitshow. I mused:

Maybe I should write about Hoboken,

in which I’ve lived for 11 years and worked for 20.

If I capture Hoboken, I capture life, right?

I could illustrate it with my drawings!

Then I remember that Williams, in Paterson, upholds the northern Jersey city as a microcosm, and I decide to read the whole damn poem. At the very least, I’ll squeeze a column out of it. That will give me an excuse to pontificate about poetry: What is it? What is its point? I’ll return to that question.

Paterson is ostensibly about Paterson, but it’s really about the world, because, Williams assures us, “Anywhere is everywhere.” The book is also about a man, because “a man in himself is a city.” (I dig that metaphor, it reminds me of Minsky’s view of a mind as a “society” of frenemies.)

The “man” is presumably Williams (1883-1963), who in addition to being a poet was a physician. He delivered lots of babies, saw birth, sickness, death up close. Great poetic grist. Plus, doctoring, unlike poem-writing, pays the bills. (Hmm, if anywhere is everywhere, does that mean anyone is everyone? Wait, does that mean I am… you know who? Nah.)

Paterson contains plenty of the clipped, cryptic lines that signify “poetry.” Book I begins:

To make a start

out of particulars

and make them general, rolling

up the sum, by defective means—

Sniffing the trees,

just another dog

among a lot of dogs. What

else is there? And to do?

That’s typical: humble imagery (dogs sniffing trees) jumbled together with vaguely philosophical stuff (particulars denoting the general). Williams fleshes out his text with prose asides, historical documents, news stories, letters.

All this gives Paterson a pleasingly pointillist, nitty-gritty quality. Williams extols the Passaic River, which runs through Paterson, and Paterson Falls. Paterson Falls isn’t merely pretty, because nothing is merely pretty, especially not in New Jersey.

Paterson Falls once powered a mill, and it provides a site for feats of derring-do. One daredevil crosses the falls on a rope. Another fool plunges over the falls and vanishes. Folks find his carcass stuck in a chunk of ice months later.

Williams documents atrocities that unfold in Paterson: rapes, robberies, murders, infanticide, hangings. Whites fight each other, enslave blacks, slaughter Native Americans. How can the world be so lovely and ugly? Good question, the old problem of evil. Williams wisely doesn’t try to solve the problem, just rubs our faces in it.

Williams frets, perhaps too much, over what poetry should and shouldn’t be. He disapproves of Eliot’s Wasteland, finding it too pompously erudite. Williams prefers the earthiness of Joyce’s Ulysses. A novel, not a poem, but still.

Williams, deliverer of babies, wants to give birth to a new language, an unpretentious, working-class, American language. At times he resembles one of those philosophers who fusses so much over definitions that he never gets to his point.

The blue scribbles are mine. I’m not sure who wrote the maroon marginalia, maybe my sister Wendy.

And that brings me back to the question: What is poetry’s point? Because Paterson, in addition to being about Paterson, is about poetry. Paterson recounts a Q&A in which an interviewer asks Williams “what poetry is.” Williams replies that poetry is “language charged with emotion. It’s words, rhythmically organized… A poem is a complete little universe.”

The interviewer springs his gotcha. He quotes a Williams poem that includes the following lines:

2 partridges

2 mallard ducks

a Dungeness crab

The interviewer says this sounds like a “fashionable grocery list.” Williams gamely confirms that it is indeed a grocery list. He adds, “Anything is good material for poetry. Anything.”

Let me offer my own answer to the question: What is poetry? Poetry counters our habituation. It helps us pay attention to things we take for granted. That’s the point.

Poetry is a medium for mysticism, by which I mean seeing the world as it truly is. Seeing the world as it is ain’t easy, and capturing what you see in words is impossible. But the poet tries, risking ridicule.

The mystical schtick—anywhere is everywhere, anyone is everyone, thou art that, yada yada—is easy to ridicule too. If you see one place as every place, one person as every person, is your vision clear, or blurry? Maybe you should have your eyes checked.

Here’s another problem: You know how some dogs don’t get the concept of pointing? You threw the ball, it’s in the bush. But when you point at the bush, your dog stares at your finger, head cocked, half-wagging his tail. He’s confused.

Poetry can provoke a similar response. Take Williams’s famous poem The Red Wheelelbarrow:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

That’s it, the whole poem. It might make you cock your head and think:

Huh?

What the fuck,

I don’t get it.

That’s because you’re staring at the poem, which is pointing at something else. What is it? What is that something else? No one can say, not Buddha, not Woolf, not Hawking or Witten, not Williams. No one.

If the something else

could be spelled out,

we wouldn’t need

poetry. Like, duh.

Literary critics are especially susceptible to the pointing problem. Even poets can succumb. They get so fixated on their art that they forget what it’s for. Williams agonizes over this pitfall. Paterson includes a letter from a poet who accuses him of caring more about “literature” than about real, suffering people, like her.

Ouch. I relate. A former girlfriend diagnosed me with “The Coldness.”

One way for poems to overcome the pointing problem is to be self-negating. Ideally, they’ll deliver their message and immolate themselves, like the tapes in Mission Impossible. Paterson, which seethes with irony and Williams’s self-doubt, has this quality of self-negation.

So does negative theology, which insists that god transcends description while yammering about Him/Her/Them/It. Poetry, if it’s good, has this same self-contradicting quality, but even more so.

Poetry is religion stripped of god, faith, belief--even belief in words. You stand before the mysterium tremendum, naked, fighting the impulse to cross your hands before your crotch. As if the mysterium tremendum cares.

Paterson works for me. It cuts through my habituation, it helps me see the weirdness. It reminds me that anything—a Jersey city, a waterfall, a grocery list, a wave function--is a synecdoche for everything.

Now that I’ve finished Paterson, I’m thinking of driving to Paterson. This weekend, the city is hosting the “Paterson Great Falls Festival.” It might be fun to see The Falls after hearing Williams go on and on about it.

Or maybe I’ll just stay here in the town I like to call Ho-Ho-Hoboken. My enthusiasm for Hoboken, the book, is waning, but not my enthusiasm for my home. And as you know, anywhere is everywhere, especially in New Jersey.

Further Reading:

How Ho-Ho-Hoboken Became My Home

For more riffs on literature, see Solzhenitsyn, the Gulag and Free Will, Surfing Woolf’s “The Waves”, Woolf Versus Buddha, I Read Gravity’s Rainbow So You Don’t Have To, Is David Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest” Really, Like, Great?, My Bloomsday Tribute to James Joyce, Greatest Mind-Scientist Ever, Henry James, The Ambassadors and the Dithering Hero, The Golden Bowl and the Combinatorial Explosion of Theories of Mind, Free Will, War and the Tolstoy Paradox, Moby Dick and Hawking’s “Ultimate Theory”, Jack London, Liberal Arts and the Dream of Total Knowledge.