Solzhenitsyn, the Gulag and Free Will

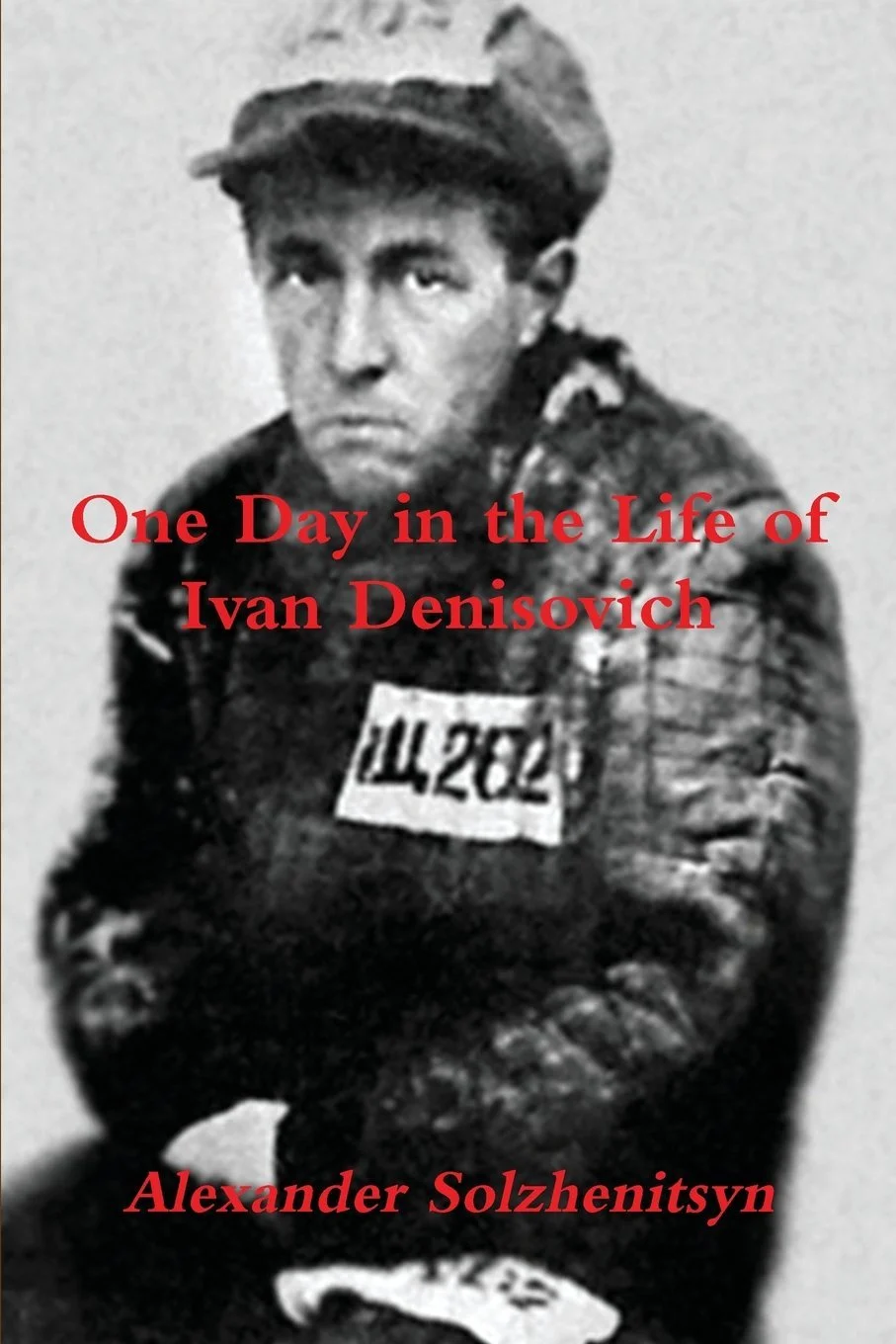

The sourpuss is Solzhenitsyn himself, photographed in a Siberian prison in 1953.

HOBOKEN, JULY 12, 2025. I recently binged a bunch of novels about upper-class twits lollygagging through life: To the Lighthouse and The Waves by Woolf, The Ambassadors and Golden Bowl by James.

For balance, and because it seems fitting for our historical moment, I just read One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. This is the first of Solzhenitsyn’s fictional depictions of the Gulag, the Soviet system of forced-labor camps. Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008) knows the Gulag well, because he did eight years hard time for slighting Stalin in a letter.

Solzhenitsyn gives us a gritty, deadpan account of a typical day in a prison. The novel strikes me as hyper-realistic, although my only first-hand taste of incarceration comes from a long weekend I spent in a Key West jail in 1973.

Ivan’s rags can’t keep out the cold, his meals of bread and gruel can’t quell his gnawing hunger. If he flees or merely deviates from his assigned tasks, guards will shoot him or toss him in “the hole,” which we never see but sounds bad. It’s a hole within a hole, a meta-punishment.

At first glance, the Gulag is utterly unlike the worlds described by Woolf and James. Solzhenitsyn’s hero, Ivan, inhabits a parallel universe. Or does he? Ivan the inmate, I’ve decided, has a lot in common with the “free” characters of Woolf and James.

Reading Solzhenitsyn after Woolf and James reminds me how maddeningly adaptable we humans are. We get habituated to heaven and hell alike. We find the downside of a vacation by the sea (the setting of To the Lighthouse), the upside of a Siberian prison. Most days we dwell in limbo, a.k.a. the human condition.

Like Mrs. Ramsay in Lighthouse, Ivan navigates complex social situations, he tries to be kind without being a pushover, strong without being a bully. What Ivan feels trapped in the Gulag is not dissimilar to what Mrs. Ramsay feels trapped in a bourgeois marriage. Anxiety, anticipation, affection, irritation, despair, satisfaction. The usual emotional jumble.

Solzhenitsyn describes Ivan’s day with painstaking granularity, and yet Ivan’s plight takes on a mythical, Sisyphean grandeur. Yeah, Ivan is one particular guy in one particular time and place, and yet he stands for all of us. More than pity, we feel affinity for this poor schmuck.

A grim take on One Day is that none of us, not even aristocrats with maids—not even billionaire tech bros!--is truly free. We’re all victims of fate, of forces beyond our control. Fate strokes some of us, bashes others, not because we deserve it but just because. It’s random.

Let’s call this the Sapolsky Interpretation. Robert Sapolsky is the neuroscientist who denies free will, and who insists that none of us deserves what we get, good or bad, everything comes down to luck.

I reject the Sapolsky Interpretation, and I’m pretty sure Solzhenitsyn would have too. If fate deals you a shitty hand, Solzhenitsyn implies, you still have free will. Ivan constantly faces moral choices. He’s tough but a nice guy, he tries to do right by his fellow inmates, although he never makes a big deal about it.

Wrongly convicted of being a German spy, Ivan was imprisoned unjustly. And yet he doesn’t succumb to rage or despair. He takes pleasure in a cigarette, crust of bread, dollop of gruel. The spare sensuality of these scenes recalls Jake savoring wine and fresh-caught trout in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises.

Ivan finds solace in his slavish labors. His main task is building a brick wall. He has to keep stirring the mortar, because otherwise it will freeze. He slaps the mortar down and slides the bricks into place, making sure they’re properly aligned.

Ivan keeps laying bricks even after the sun sets and the foreman tells him it’s time to quit. Ivan is in a groove, he wants to keep going because he’s proud of his work. It’s like The Bridge On the River Kwai without the whistling and schmaltz.

Here’s a more extreme comparison: an ayahuasca trip recounted by psychologist Benny Shanon in his book The Antipodes of the Mind. During the trip, Shanon hallucinates a reenactment of the Biblical story of King Zedekiah. A rival king conquers Zedekiah, butchers his sons in front of him, then gouges out his eyes. Yeah, real Old Testament shit.

How does Zedekiah react? Blind and in chains, he sings a hymn of thanks to God. Shanon, pondering this vision, concludes that no matter how bad things get, we can choose to be grateful, to say Yes! to life. That’s the ultimate act of free will.

Okay, that’s a high bar, so let me add a caveat: Through a quirk of brain chemistry or whatever, some of us, like Virginia Woolf, find existence unbearable. Objectively, Woolf’s life was terrific. She was an acclaimed writer, married to a loving man. Subjectively, she found life hellish and opted out.

Another extremely important caveat: Maybe Solzhenitsyn, like Zedekiah, was grateful for the miracle of existence. At the end of One Day Ivan thinks, before falling asleep, “The end of an unclouded day. Almost a happy one.”

But Solzhenitsyn isn’t preaching mystical acceptance of whatever life throws at us. Far from it. The cruelty of the Soviet system appalls him, he’s determined to do something about it. At the risk of being thrown back in prison, or worse, Solzhenitsyn exposes the horrors of the Gulag, because he hopes to end this perversion of communist ideals.

And holy shit, he succeeds! Solzhenitsyn’s writings help catalyze the collapse of the Gulag and, eventually, the whole failed Soviet experiment. What a spectacular demonstration that injustice is a solvable problem and not a manifestation of cosmic randomness! Solzhenitsyn also proves that a single person, exercising free will, can change history.

Okay, yeah, Russia isn’t exactly a beacon of freedom and justice now, and the U.S. is lurching toward dictatorship, too. But still. One step forward…

Further Reading:

For more riffs on literature, see Surfing Woolf’s “The Waves”, Woolf Versus Buddha, I Read Gravity’s Rainbow So You Don’t Have To, Is David Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest” Really, Like, Great?, My Bloomsday Tribute to James Joyce, Greatest Mind-Scientist Ever, Henry James, The Ambassadors and the Dithering Hero, The Golden Bowl and the Combinatorial Explosion of Theories of Mind, Free Will, War and the Tolstoy Paradox, Moby Dick and Hawking’s “Ultimate Theory”, Jack London, Liberal Arts and the Dream of Total Knowledge.