CHAPTER TWO

The Cognitive Scientist

Strange Loops All the Way Down

By the time I flew to Indiana to meet Douglas Hofstadter, I was so steeped in his writings that I found myself thinking like him, or like I like to think he thinks. I thought, I’m looking out the plane at a plain, which is also a plane. In my notebook I jotted, Indiana, the Blank State. But the landscape wasn’t blank. It was an Escher print, a recursive geometric puzzle receding to a blurred horizon, a metaphor for infinity.

My feeble punning efforts made me appreciate punny-man Hofstadter all the more. For him, the world is a cosmic, multidimensional pun seething with meanings. His writings, especially his first book, Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid, dwell on deep isomorphisms, or resemblances, between patterns in nature and in mathematics, art, music.

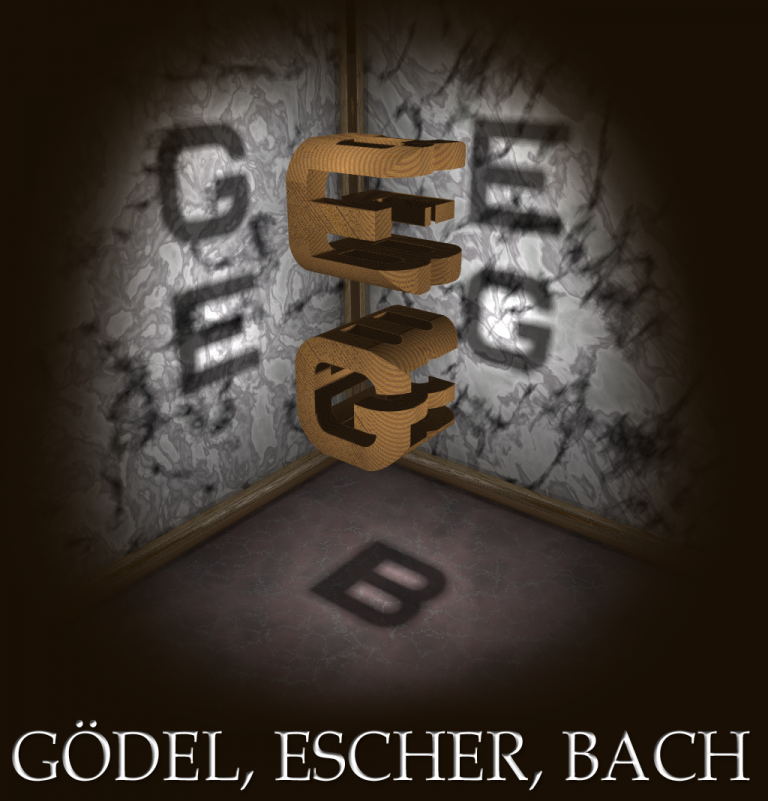

Gödel, Escher and Bach, the mathematician, artist and musician, are isomorphs of each other and projections of a deeper structure. An image at the beginning of the book illustrates this idea. An odd geometric object, a three-dimensional rune, hovers in a cube. Light shining through it casts shadows on the walls of the cube: G, E, B. What is the object? Hofstadter’s book? His mind? His God? Hofstadter calls Gödel, Escher, Bach “a statement of my religion.”

He is obsessed with self-reference and recursion, with things that do things to themselves, repeatedly.[1] These concepts are embedded in what he calls the “strange loop.” This is Hofstadter’s big idea, which winds through and binds all his work. A strange loop is something that does something to itself, that defines, reflects, restricts, contradicts, plays with and creates itself. Like Gödel’s theorem about the limits of theorems. Escher’s drawing of hands drawing each other. Bach’s fugues, which curl back upon themselves like Mobius strips. Language, which consists of words defined by other words, is a gigantic strange loop, and so are music, art, mathematics, science and all of human culture. Human minds are the strangest, loopiest loops of all.

Gödel, Escher, Bach is a strange loop too. It has a fugue-like structure, with recurrent themes and motifs, and it constantly talks about itself. Every other chapter is a Lewis Carroll-esque dialogue between Tortoise and Achilles, as well as other mythical and real characters, about what Hofstadter just talked about. Hofstadter joins Tortoise and Achilles in the final dialogue, along with Charles Babbage and Alan Turing.

Martin Gardner, the mathematics columnist for Scientific American (whom Hofstadter replaced after Gardner retired), said of Gödel, Escher, Bach: “Every few decades an unknown author brings out a book of such depth, clarity, range, wit, beauty and originality that it is recognized at once as a major literary event. [This] is such a work.” Only re-reading it before flying to Indiana did I appreciate that Gödel, Escher, Bach is a 777-page assault on the mind-body problem. Strange loops serve, for Hofstadter, as a general principle of cognition, whatever form it takes. Intelligent machines, if we ever build them, and aliens, if we ever encounter them, must have loopy minds, as we do.

Hofstadter explains, in painstaking detail, how purely physical processes generate minds and meaning. His answer is that loops at the level of particles, of electrons and quarks, give rise to loops at the level of biology, genes and neurons, and eventually at the level of symbols, concepts and meaning. Our minds are symbol-processing strange loops that are generated by and exert influence over matter. Weave all these loops together and you get the “eternal golden braid” of existence.

Gödel, Escher, Bach is at once highly technical—with detailed digressions on physics, mathematical logic, computer languages and DNA transcription—and trippy. Psychedelics, at their best, reveal reality as an endless play of forms, a joyous dance that transcends bad and good, that is simply beautiful, so beautiful your brain melts and leaks out your ears, as an acid head might put it. Hofstadter is one of those rare souls who dwells permanently in that sublime, magical realm. Or so I imagined when I first encountered his work long ago, before I became a science writer. He is also blessed with the talent to give us glimpses of his world.

Hofstadter’s detractors dismiss him as “clever.” That is grossly unfair, but I know what they mean. His playfulness can be relentless, exhausting. You can’t just read Gödel, Escher, Bach, you have to study it. Hofstadter assigns exercises, which he assures you will be lots of fun. “Try it!” he orders. At times, he resembles a too-enthusiastic camp counselor exhorting you to play a super cool game. If you skip his exercises (as I usually do), you feel lazy and guilty, and start to resent the counselor.

There is something chilly, almost inhuman, about Gödel, Escher, Bach. It delves so deeply into the machine code of meaning that it leaves ordinary human meaning behind. Hofstadter also feared after writing the book that many readers missed its central point. He had solved the mind-body problem, the mystery of who we really are. Hofstadter wrote I Am a Strange Loop, published in 2007, to spell out this theme more clearly, to explain “what an ‘I’ is.” He writes, “I hope this book will make you reflect in fresh ways on what being human is all about—in fact, on what just-plain being is all about.”

Strange Loop is warmer than Gödel, Escher, Bach. It is not just a book about meaning, it is a meaningful book, because it grapples with grief. Hofstadter says as much in the preface. Referring to himself, as he often does, in the third person, he notes that the author of Strange Loop “has known considerably more suffering, sadness and soul-searching” than the author of Gödel, Escher, Bach.

In 1993, Hofstader’s wife Carol died “very suddenly, essentially without warning, of a brain tumor.” Not all deaths are tragic. This one was. Carol was 42, and she left her husband with two children, two and five years old. How do you make sense of such a death if you don’t believe in God? Souls? Heaven? Hofstadter couldn’t make sense of it, but he tried.

One chapter of Strange Loop consists of email exchanges between Hofstadter and his friend Daniel Dennett, in which Hofstadter vents his grief. Although his wife’s body is gone, Hofstadter writes, her “consciousness, her interiority, remains on this planet.” Just as the Sun is ringed by a radiant solar corona, still visible even when it is eclipsed, so do we, when eclipsed by death, endure in the minds of those who knew and loved us. We live on as “soular coronas.”[2]

I resist envy, as a matter of principle, but it was hard not to envy Hofstadter. From the perspective of my dim, halting self, he seemed blessed with the ideal scientific-artistic-mystical mind, a marvelous, frictionless machine for generating epiphanies. Yes, he has endured tribulations, like all mortals, but his intellect helped him see existence as sublime, in spite of everything. Again, so I imagined. I also owed Hofstadter a debt. Reading Gödel, Escher, Bach and “Metamagical Themas,” his column for Scientific American, in the early 1980s made me want to become a science journalist.

I was mulling all this over as I flew south over the flatlands of Indiana. I scanned my sheet of questions. How Hofstadter became interested in music, mathematics, the mind-body problem. How he was affected by the death of his wife, and the disability of a sister. The famous lines popped into my head: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all/Ye know on Earth, and all ye need to know.” This could be Hofstadter’s motto. At the top of my question sheet I scribbled: “Keats: Beauty = Truth?” Yeah, ask about that.

* * * * *

After landing in Indianapolis, I drove a rental car south on Route 37. As I approached Bloomington, the landscape began undulating, sprouting groves and rocky knolls, like premonitions. As I pulled into the driveway behind Hofstadter’s two-story brick home, he emerged from his house to greet me, wearing a topologically and chromatically complicated sweater-jacket. His smile seemed forced, more like a grimace. His head looked too large for the stalk of his body, and he appeared younger and older than his age, boyish and wizened. He peered at me warily from beneath dark eyebrows.

Entering the house, we stepped over an ancient golden retriever. The dog strained to lift his white-muzzled head, and his rheumy eyes took us in with a bewildered expression. I trailed Hofstadter into a living room crammed with books, vinyl records, sheet music, concert posters, busts of composers, a piano and other musical instruments. Pale light fell through filmy, curtained windows. I offered a pleasantry about how “lived in” his home felt.

“What do you mean?” Hofstadter asked sharply.

The house felt filled with memories, I said carefully, with things accumulated over the course of a long, well-lived life.

It is filled with memories, he said, with things that date back to his childhood, like books and records that belonged to his parents. He fetched a scrapbook and showed me a telegram that congratulated his father, Robert, on winning the 1961 Nobel Prize in physics. The telegram was signed by President John F. Kennedy. “I am a person who is very deeply connected to the past,” Hofstadter said. His second wife, whom he married in 2012, doesn’t share his fondness for old things. She lives in a different house, newer, cleaner.

I settled on one couch, Hofstadter on another perpendicular to mine. He occasionally smiled or chuckled, but his default expression was grim, inward-looking. He sat slightly hunched over, head tipped forward, as if steeled for a blow. He became animated when I asked how he got interested in the mind-body problem. His fascination with the mind had emotional as well as intellectual roots. His younger sister Molly was born with a neurological disorder, and she never learned to speak. His parents considered but did not pursue brain surgery to search for the cause of the disability.

The prospect of the operation “was very, very eerie to me, anxiety-provoking and scary. And it was the first time that I actually thought about the idea that what goes on inside one’s skull is what is giving rise to one’s so-called consciousness. And I use ‘so-called’ because I think of it as an illusion.” Hofstadter might have meant to provoke me with this assertion, but I let it pass (and I’ll examine it later).

He consumed books on the brain, including one by Wilder Penfield, a neurosurgeon who performed experiments on epileptics. After cutting away their skulls, Penfield stuck wires in the epileptics’ brains and zapped them with electricity. Patients stimulated in this way had visions and recalled long-forgotten scenes from their childhoods.

“I realized that if you look at a brain, it would just look like an ordinary lump of stuff. And you couldn’t see anything related to thought, whatsoever. It was just some kind of meat, you could eat, a brain. How did that give rise to all of these colors and sensations inside? That was a scary but fascinating issue.”

Hofstadter was also entranced as a child by things that do things to themselves. He dwelled on the strangeness of multiplying 3 times 3 times 3, or of finding two identical numbers that when multiplied produced 2. (His father, after young Douglas mentioned the latter puzzle, told him he had discovered something called a “square root.”) “And of course I loved paradoxical things, like ‘This sentence is false.’ The twistiness of such things was very interesting to me.”[3]

Browsing in a bookstore in his mid-teens, Hofstadter came across a book that explained Gödel’s theorem, one of the most momentous advances in the history of ideas. In 1930 Kurt Gödel, a 24-year-old Austrian logician, proved that any axiomatic system powerful enough to describe the natural numbers (0, 1, 2, 3,...) is “incomplete.” That is, it will generate infinitely many true statements that it cannot prove.

“It was magical!” Hofstadter exclaimed, as if reliving the thrill of his youthful discovery. Gödel provided deep insights into “the nature of symbols and language and meaning,” and he showed that a formal system, which “looked on the surface to be a completely inert structure,” could refer to and yield insights into itself. “A sentence could say, ‘This sentence cannot be proven in this system.’”

Hofstadter suspected that similar self-referential processes transform neural operations into mental ones. “A brain doesn’t look like anything that a priori can support consciousness,” he said. “It just looks like a piece of flesh. But because of the looping around that can take place, because of the perceptual processes, because of the way that the neurons can respond, you get a self-referential structure built up in it, and things can happen.”

Hofstadter plunged into mathematics and logic in order to pursue his ideas further. He gained access to a computer at Stanford University, where his father worked, and programmed it to generate sentences based on recursive rules. He delighted in feeding punch cards to the mainframe, which ground through the program, lights flashing, and spewed out reams of paper covered with symbols. If a brain can become self-conscious through self-referential processes, he thought, perhaps a computer can too.

Hofstadter and friend, Eugene, Oregon, 1972.

Recalling these childhood adventures, Hofstadter was transported by the same enthusiasm that animates his writings. I expected that. What I did not expect was the intensity of his antipathies. Take, for example, his response to my question about Buddhism. I assumed that Hofstadter had an affinity for it, because he, like Buddhists, sees the self as illusory. Gödel, Escher, Bach also riffs repeatedly on Zen.

“I hated Zen,” Hofstadter replied. Zen was “the antithesis of everything I believed in.” The Zen riddles called koans, like what is the sound of one hand clapping or what did your face look like before your parents were born, were “self-contradictory pieces of nonsense, absolute nonsense.” Precisely because they were so ridiculous, koans became a “pet peeve that I played around with.” That is how they ended up in Gödel, Escher, Bach.

When I asked if he ever considered becoming a philosopher, Hofstadter said he disliked philosophers. He found them obscure, simple-minded, shallow, dogmatic. “They fell for all the obvious ideas and then latched onto them with a fury or fervor that I couldn't understand.” Bertrand Russell “was the quintessence of that for me. Gödel was deep, and Russell was shallow.” There are exceptions, such as his old friend Daniel Dennett, but most philosopher are “players with words.”

He hated philosophical jargon, like metaphysics and ontology, and Latin terms like qua and cetiris paribus. “I just found it pompous, pretentious, show off-y, and empty.” Philosophers of mind were the worst. “Reductionism, functionalism, everything was an ism.” Many philosophers, he suspected, “would have liked to be scientists but weren’t good enough.” He brooded a moment. “I don’t mean to be too harsh, because we all have our limitations. We all have things we would have loved to do and couldn’t. But…”

A question about computer science provoked another outburst. Hofstadter assured me that he never considered becoming a computer scientist. “I hated nerds, and to me the world of computers was filled with very nerdy people,” he said. “I didn't want to hang around people who were going to do nothing but talk about computers.” Young Hofstadter aspired to be a mathematician, but he hit a ceiling toward the end of college. By that time, he had decided mathematicians were as “weird and nerdy” as computer scientists, so he happily switched to physics, his father’s field. “This could be sour grapes, but I could say, ‘Phew! I’m glad to be out of math,’” he said.

Physics seemed, initially, like the perfect fit. As a boy, he loved listening to his father talk to his fellow physicists, using terms like angular momentum, wave mechanics, electron scattering, klystron tubes. Unlike computer scientists and mathematicians, physicists weren’t nerdy. Physicists “loved the mountains, they loved nature, they loved music, they loved art, they loved words, they loved history.” Physicists were “the most cultured people in the whole world,” he said. “That was the kind of company I wanted to keep.”

Hofstadter cherished stories about the pioneers of particle physics, such as Wolfgang Pauli. In the 1930s, observations of radioactive decay didn’t make any sense. They seemed to violate the laws of conservation of energy and momentum. Pauli proposed the existence of a new particle, the neutrino, to salvage these conservation laws, but he did so with reluctance, even “shame,” Hofstadter said. “One particle, to save three of the most fundamental laws of physics!” Experiments have confirmed the existence of neutrinos.

Hofstadter entered particle physics, which seeks the fundamental stuff of reality, but he came to loathe that field too. “I became more and more lost and repelled by the ugliness of theories that I was seeing. I just could not stomach any of it.” By the early 1970s, when he was a graduate student at the University of Oregon, physicists were proposing new particles left and right with little or no justification. In a seminar, Hofstadter savagely criticized a paper that postulated the existence of 156 new particles. He finished his presentation by declaring that proponents of the theory “have no sense of shame.” He shouted, “I quit!” and stomped out of the room.

Hofstadter switched to solid-state physics, although he had disdained it as glorified engineering. In 1974, studying the behavior of a crystal immersed in a magnetic field, he made an unexpected discovery. The energy values of electrons in the crystal formed a “wispy” graph with remarkable properties. The term “fractal” hadn't been invented yet, but the graph is a fractal. When you examine a fractal at smaller scales, the same pattern recurs with slight variations. Hofstadter called the graph “Gplot,” but others have dubbed it “Hofstadter’s butterfly.”

Hofstadter’s graph of the Gplot.

I was struck, listening to Hofstadter, by his aesthetic sensitivity. Beauty, it seemed, is at least as important to him as truth. I remembered the question I had scribbled down in the plane. Your work, I said, reminds me of the old Keats aphorism, Beauty is truth…He snorted. “That’s nonsense. Absolute junk. That’s the opposite of what’s true. I hate that phrase.” He was so vehement that I started laughing. “Germany killed six million Jews,” he said, scowling. “That's true. Does that make it beautiful? Come on. Nonsense.” I wasn’t laughing now. But your writing is so beautiful, I said, to mollify him, and because it is true.

“I think we should try to bring as much beauty into the world as we can,” he said, “since the world is so non-beautiful!” He seemed genuinely furious. But, but, I sputtered. Your writing draws attention to these beautiful, deep structures—in music, mathematics, in our selves.

“Hitler had a self, but not a beautiful one,” he retorted. Not every strange loop “is a beautiful thing that gives rise to beauty in the world. It can give rise to mass murderers and serial killers and rapists.” Hofstadter saw the world as “filled with anguish." During the course of evolution, “trillions of creatures have suffered at the hands and claws of others. I don’t think of that as beautiful in any way, shape or form, I think of it as horrible.” He called evolution “horrendous,” “ruthless,” “violent.”

Fortunately, some humans are capable of recognizing and overcoming this natural violence and cruelty. He chose at an early age not to eat animals or wear pieces of them, and he strives to be kind to people. “I see the world as being the site of tremendous pain. But for that very reason I think it’s very important to try to be gentle and kind and empathetic and compassionate, and to help suffering people. Because the world is so cruel and merciless.”

Even as a child, Hofstadter said, he was “very, very aware of the sad sides of life.” He clipped out articles about murders and kidnappings, “horrible events that wrenched my gut,” to honor the victims. “I felt that out of respect to these people, I would clip the article, so in some sense that little shred of them remained alive.” Hofstadter still had the clippings.

From adolescence on, he was also tormented by yearnings for “romance.” He loved romantic films and music. Songs by Rodgers and Hart, Cole Porter and George Gershwin were favorites. These “permeated me and gave me an extremely romantic vision of life.” He desired a specific kind of female beauty, which unfortunately also attracted other males. This “narrow resonance curve” meant that he was “almost doomed to be a failure, to not find a girlfriend I wanted.” As a young man he had moments of happiness, even joy, composing music on a piano, swapping “bon mots” with friends. But his longing for love gnawed at him.

“I don't want to say that if you had met me at that age that you would have said, ‘That’s the unhappiest person I’ve ever seen.’ You’d probably say, ‘That’s a funny guy. He’s got a good sense of humor, but he’s sad. He’s a sad guy. He’s very fun, he has a bright, chipper side, and he’s the first to come to your aid if you are sad. He’ll try to cheer you up, and he’s never one to make you feel sad, or to say that life is unhappy. But he has suffered, he has been striving and struggling constantly. He has had bad luck with romances, and it really hurts him.’ That’s what you’d say. ‘Poor guy, he’s struck out.’”

Hofstadter didn’t have his first serious relationship until his mid-30s, after Gödel, Escher, Bach was published. When I asked if he struggled to keep his melancholy out of the book, Hofstadter scowled. “Why would I even think of bringing in melancholy,” he said. “It was irrelevant.”

But as time went on, he revealed more of himself in his writing, “happy things but also a lot of sad things.” He realized that “first-person stories are very, very powerful ways of getting ideas across.” That was why in I Am a Strange Loop he wrote about the death of Carol, the woman with whom he finally found love. They married in 1985, and she died eight years later. After her death Hofstadter felt “infinite sadness,” but sadness wasn’t new to him. He had always carried it within him.

* * * * *

Some of Hofstadter’s philosophical positions seem self-punishing. Although his work strikes me as one long argument against the reduction of minds to physics, he calls himself a reductionist. “We should remember,” he writes in Gödel, Escher, Bach, “that physical law is what makes it all happen, way, way down in neural nooks and crannies which are too remote for us to reach with our high level introspective probes.”

Hofstadter asserts that consciousness is “not as deep a mystery as it seems.” It is a pseudo-problem, because consciousness is an “illusion.” By this, Hofstadter seems to mean that our conscious thoughts and perceptions are often misleading, and they are trivial compared to all the computation going on below the level of our awareness.[4]

Hofstadter also contends that free will is an illusion. I told him that simple introspection made me believe in free will. At key times in my life, I have all-too-consciously faced choices, agonized over them, and made decisions, for example about my career and love life.

“I don’t feel as though I have made any decisions,” he replied. “I feel like decisions are made for me by the forces inside my brain.” He paused. “I don’t object to the notion that there is will, and a battle of wills, but there is nothing free.” If he stops to buy gas and spots potato chips in the gas station, he is subject to competing forces. One, he is hungry. Two, he’s worried about his weight. The stronger force prevails. “There is no freedom. There’s a conflict, a tussle, battle free-for-all.” He paused. “An un-free for all, combat, where the stronger force wins.”

What about the moral reasoning that led him to become a vegetarian? As a child, he replied, he saw “carcasses being unloaded from trucks into the back of grocery stores. I asked my parents what meat was and found out.” Eventually his horror at the slaughter of animals overcame his desire to eat meat and to conform, to do what most people do. “At that point, I snapped, and became a vegetarian.”

Hofstadter in Beijing, China, 2018.

Hofstadter is, in most respects, a hard-core skeptic, who denies himself beliefs that comfort others. He rejects God, the afterlife, the soul and free will. He seems to derive comfort, however, from his faith in a Platonic realm of sublime forms. The forms exist independently of us, but if we are lucky, we can discern them.

His Platonism emerged when he talked about the quantum fractal that bears his name, Hofstadter’s butterfly. He compared it to a shell on the beach, half-buried, waiting for him to stroll past. “It was partly covered, mostly covered, but I happened to be the right person in the right place at the right time, because I had had preparation to recognize it.”

Many scientists and philosophers would agree with Hofstadter about the Platonic nature of mathematical and scientific truths like the Pythagorean theorem or general relativity. His more radical claim is that works of music, poetry and art are also discovered. His conviction, again, comes from personal experience. When working on a book, Hofstadter writes, deletes, re-writes, revises. “I keep doing it over and over again until I produce something I am happy with,” he said. “It’s not like I’m really inventing anything. I’m sort of just discovering things that work. And there’s a lot of chance involved.”

Hofstadter’s Platonic view of his work is, from one perspective, arrogant, because it implies that his ideas and their formulations are transcendent and timeless, like pi. But it is also humble, even self-negating, and consistent with his rejection of free will. Hofstadter didn’t create Gödel, Escher, Bach. He just happened to notice it peeking from the sand while he was strolling along the shore of Platonic forms.

Hofstadter believes that even our responses to art have a Platonic quality, and that there is an objectively true, “correct” way to respond to a painting, poem or passage of music. This perspective implies that a beauty-meter and meaning-meter, which render objective aesthetic judgments, might be possible. To illustrate his view, Hofstadter told me a story. He was teaching a seminar, “Fugues, Canons and Inventions,” in the music school of Indiana University. One day, he played a snippet from a Handel overture and asked if the students heard any “sadness,” or “wistfulness.” They didn’t. “They just heard it as happy.”

The next day, Hofstadter played the piece again. This time, he said he would raise his hand when he heard sadness, and he asked the students to raise their hands if they heard it, too. Many of the students raised their hands when Hofstadter did. “One student said something I liked: ‘Now that I listen carefully, I can hear the sadness throughout.’ And I thought, ‘Wow, what a revolution.’ They were all saying it was happy at the beginning. And at the end, they hear that pervading the happiness—sort of under, hidden inside it—is unhappiness.”

I’m a teacher, too, and I have a different take on this incident. Some students might have genuinely heard the sadness the second time around, but only because they succumbed to Hofstadter’s power of suggestion. Others might have pretended to hear the sadness because they wanted to curry favor with their grade-giver. Or they felt sorry for him. Or all of the above. Students are complicated creatures. I could listen to the Handel piece and judge it for myself, but there’s no point. I’ll remember Hofstadter and feel the undertow of melancholy.

* * * * *

My most serious bout of melancholy dates back to the early 1980s, around the time I discovered Hofstadter’s writings. After a woman broke up with me, I tumbled into acute depression. Her name was Faith, which somehow made it worse. Sometimes, with effort, I could go meta. That is, I could stand apart from myself and see my condition as something exotic, like a black hole in my head. I would observe the event horizon, its distortion of time and space, and think, Hmm, interesting.

Meta-ness, jumping out of a system and seeing it from the outside, is a major theme of Hoftstadter’s work. And yet going meta does not seem to mitigate his melancholy much. For intellectual and temperamental reasons, he confronts the darkness squarely. In spite of what I implied above, I don’t think Hofstadter’s vision of the world as “filled with anguish” is pathological, a projection of his tormented self. It is accurate. That makes it all the more remarkable that he has produced works brimming with beauty and joy.

Among the many striking images in his work, my favorite is a photograph in Strange Loop of Hofstadter and a bunch of students. Each sits on the lap of the person behind her, who sits on the lap of the person behind him, and so on. Pull one person from the circle and it collapses. It’s a self-sustaining, virtuous circle, a lovely loop, a lovely metaphor for humanity. Hofstadter, whose face is half-turned toward the photographer, is beaming. He looks truly happy.

Hofstadter’s riffs on the mind-body problem make me feel exhilarated when I get them and inadequate when I don’t, which is often. Trying to wrap my loopy mind around his loopy model, I always end up baffled, my mind twisted into knots. The model moves and eludes me in the same way a great but difficult poem does. I know I am in the presence of something deep and beautiful, even though I don’t quite get it. I feel like I’m missing something.

With trepidation, I told Hofstadter that he seems to straddle the realms of science and art. To my relief, he nodded. “I have one foot in science and one foot in art—where art can be taken as music, visual art, literature, those things—and another foot in physics, math and a little tiny bit in biology. And then of course psychology, cognitive science. I am a completely and totally hybrid person.”

And yet Hofstadter thinks he has solved the mind-body problem. The strange loop is the “correct” answer, he said, to the question, “What is a soul, or self, or I?” He wished more people shared his view. “I would have liked it if people had said, ‘That is the answer, that is right, that is the correct way of looking at things.’ I don't think people have said that.”

Many mind-body theorists—again, his friend Daniel Dennett is an exception—don’t like his loop model because they “don't like the idea that consciousness is an illusion.” Philosophers disrespect him because he disrespects them. “I don't cite philosophy,” he said. “I don’t use their ism words, I avoid them like plague. I don't use any jargon of theirs, and so they just ignore me. I guess that’s the price I pay.”

Trying to cheer him up, I said that his work is too original and idiosyncratic to serve as the foundation for a school of thought. It is an outlier, like all great works of art. Hofstadter nodded. One of his favorite books is Lexicon of Musical Invective, a collection of vicious reviews of great composers. “It’s extremely funny to read,” he said. “It makes you realize that no matter who you are, how much genius you have, there are going to be people who hate you.”

I don’t know any mind-body theorists who hate Hofstadter. Nor do I know any who think he has solved the mind-body problem, or even pointed in the direction of a solution. Christof Koch, although he loved Gödel, Escher, Bach, said that Hofstadter’s strange-loop model doesn’t yield testable predictions, and it’s more about self-consciousness than consciousness. David Chalmers, who earned his doctorate in philosophy under Hofstadter, never saw the strange-loop model as a solution to the hard problem of consciousness.

Hofstadter’s adamant belief in his strange-loop model explains his disbelief in consciousness, the self and free will. If we are really strange loops, then that explanation supersedes other, more traditional views of the mind-body problem, which assume that we are these things called “selves” that possess other things called “consciousness” and “free will.”

The irony is that Hofstadter has shown that mind-body stories can take many forms. They can be works of mathematics, science, philosophy, theology or art. Or, like Gödel, Escher, Bach, they can be a chimerical blend of all the above. Hofstadter might not like what I’m going to say next. But when he calls his theory correct, he’s making a category error, like calling an Escher woodcut or Virginia Woolf novel correct.[5]

Loop theory makes my loop thrum, perhaps because I share Hofstadter’s fascination with self-reference and a closely related concept, recursion. And I too suspect that at the bottom of everything, something is doing something to itself. Hofstadter explores a corollary theme in Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking, which he co-wrote with Emmanuel Sander, a French psychologist and friend. The book argues that we can never know reality, whatever that is. Our knowledge of the world consists entirely of analogies, things that resemble other things. There is no “correct” view.

Although less artful than Gödel or Loop, Surfaces fascinated me, in part because it triggered a flashback to “reading” Finnegans Wake in college. I say “reading” because I didn’t understand Finnegans Wake in any conventional sense. It is even more packed with puns and meta-meanings than Hofstadter’s work, but it moved me, the way music moves me. The narrative consists of dreams within dreams within dreams. There isn’t any reality, or ground of being, it’s dreams all the way down, a river of dreams, that whirls and eddies endlessly before circling back to its beginning. A strange loop indeed.

The mind-body problem coils like an ouroboros at the heart of philosophy, science, mathematics, art. Some experts, notably Hofstadter’s pal Dennett, strain to explain away the problem, but Hofstadter, perhaps inadvertently, makes it more mysterious. In I Am a Strange Loop, he calls the strange loop a “closed cycle.” He writes that “despite one’s sense of departing ever further from one’s origins, one winds up, to one’s shock, exactly where one had started out.” A paradigmatic strange loop is Escher’s staircase, which goes up and up and up but never gets anywhere.

Jorge Luis Borges offers another example of a strange loop in his creepy fable “Borges and I.” He describes how he, the real Borges, is oppressed by his authorial persona, Borges. Whatever he does, whatever he creates, the other Borges coopts it. “Thus is my life a flight, and I lose everything, and everything belongs to oblivion, or to him,” “Borges” writes. “I don’t know which of the two of us is writing this page.” This is the nightmarish converse of Escher’s drawing of two hands chummily bringing each other into existence. If Borges could draw, he might show two hands frantically trying to erase each other.

In 1981 I emerged from a psychedelic trance convinced that I had stumbled onto the secret of existence.[6] Creation stems from—or is—God’s identity crisis. Think of the responsibility! Being God! If God has free will, He could choose to kill Himself, and everything would vanish. Freaked out by His own omnipotence, and the possibility of His own death, God desperately flees from Himself, from the terror He feels contemplating his own divinity. He creates us, this whole crazy, cosmic human adventure, this eternal (we hope) golden braid, as a distraction.

Eventually I talked myself out of this delusion. I persuaded myself that the anxious God I had encountered, or become, during my trip was just a projection of my anxious self. But since meeting Hofstadter, that vision has been haunting me again. If there is a God, He must be a strange loop. It’s strange loops all the way down.

* * * * *

Niceness, I like to think, is my default behavior. When I’m interviewing someone, I have an extra incentive to be nice. I want subjects to like me, trust me, because they are more likely to tell me things. But often I simply like the person, and want him to like me. Sometimes I’m extra nice because I feel compassion for the subject. That’s how I felt about Hofstadter by the end of my day with him. I wanted to protect him from the world, from predators like me. His voice was hoarse. He seemed exhausted, more frail than ever.

I had no more questions for him, but I wanted to say something nice before I left, so I told him his writings had inspired me to become a science writer. He seemed pleased. I added that I loved the phrase soular corona, which Hofstadter coined in Strange Loop to describe how someone’s soul persists after death, and I had been moved by his story about Jim, the father of a friend, who has Alzheimer’s disease. Hofstadter didn't recall the details of that passage, but now that I mentioned it, he remembered being pretty proud of it. Did I have Strange Loop with me? I dug the book out of my backpack, and Hofstadter located and read the passage:

Even before Jim’s body physically dies, his soul will have become so foggy and dim that it might as well not exist at all—the soular eclipse will be in full force—and yet despite the eclipse, his soul will still exist, in partial, low-resolution copies, scattered across the globe… Where will Jim be? Not very much anywhere, admittedly, but to some extent he will be in many places at once, and to different degrees. Though terribly reduced, he will be wherever his soular corona is. Is it very sad, but it is also beautiful. In any case, it is our only consolation.

Hofstadter looked up with a sad smile. He walked me out of the house, past the ancient golden retriever, who didn’t raise his head this time. As we stopped beside my car, I wanted to hug Hofstadter, but that was out of the question. I extended my hand. Hofstadter thrust his arms out, smiling broadly, and hugged me.

* * * * *

In moments of weakness, I suspect that Hofstadter is right, free will is a fiction, a story that makes the world more meaningful. After I returned from Indiana, my girlfriend, “Emily,” dragged me to an art exhibit. I vaguely recall being irritated with her, so I was sullen and silent as we waited in a lobby outside the exhibit. I forgot whatever had been bugging me as soon as we entered the room containing the art.

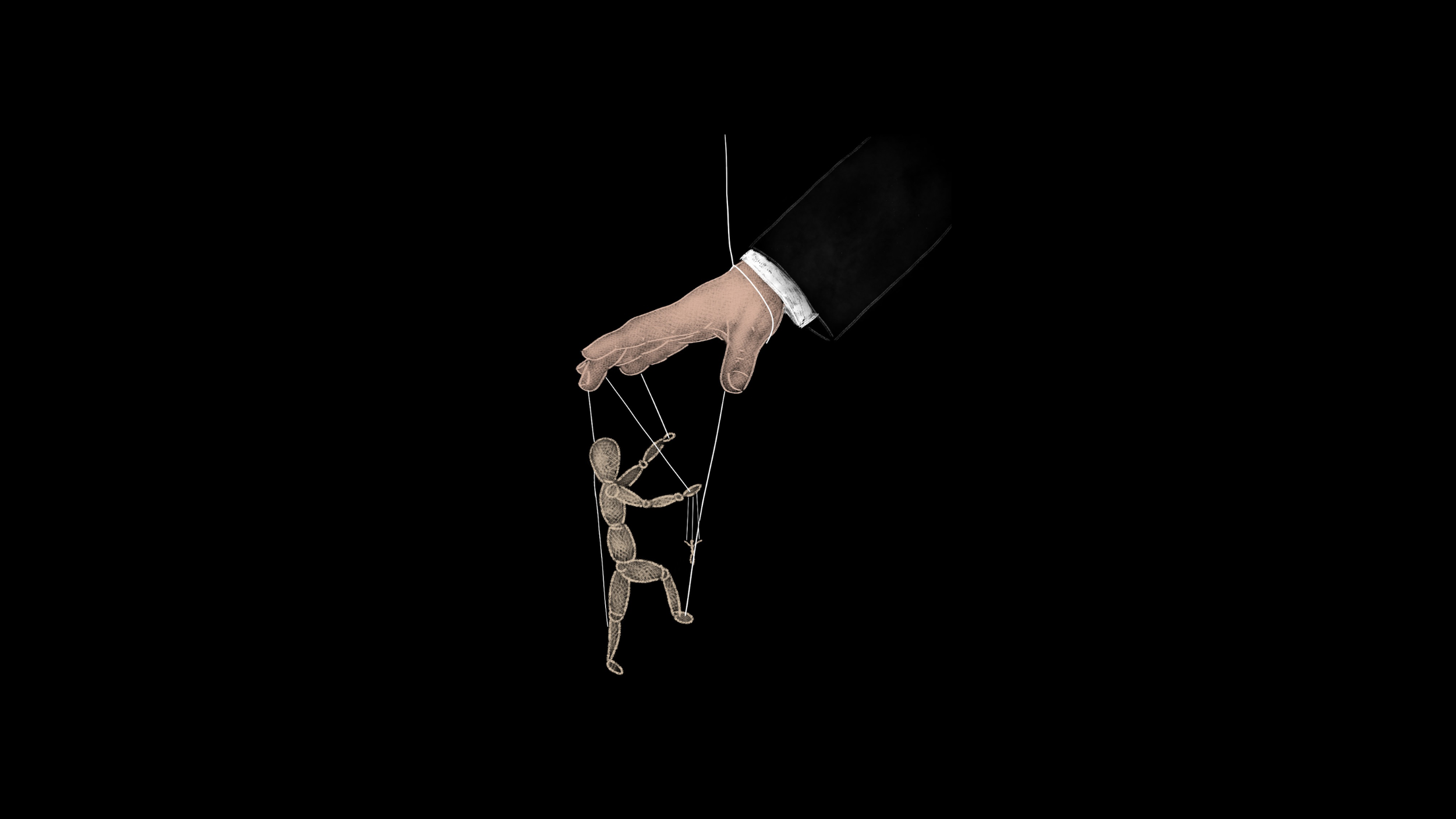

A huge marionette, which looked like Howdy Doody, dangled from the ceiling of an enormous white room. His big blue eyes were eerily animated. They blinked and swiveled back and forth, as though scanning the crowd. He was attached by chains to a large black box affixed to the ceiling, which was in turn affixed to a rectangular track.

With a mechanical clacking, the box began moving slowly along the track, gathering in and expelling chains with a loud rattling noise. Howdy moved too, his limbs and head rising and falling as the chains fed into and out of the box. He seemed in control only of his eyes, which were, somehow, expressive. He looked alternately enraged, mischievous, sad, despairing.

I thought, Okay, I get it, we’re all in chains, we have no free will, except perhaps over our emotions. We can choose to enjoy, rage at, despair over our destiny, but we can’t alter it. Ho hum. I don’t buy it. Abruptly music blared, so loudly that it startled me, and the black box violently dashed Howdy Doody against the floor, yanked him up and hurled him down again, over and over. During this ordeal Howdy Doody looked ecstatic and anguished. I laughed at him and felt sorry for him without knowing why. Only gradually did I realize that the loudspeakers were blaring the old rhythm-and-blues classic “When A Man Loves a Woman.”[7]

Love is the supreme, sublime human emotion and experience. And we are never so lacking in free will, so enslaved by desire, as when we are in love, and only love can break your heart, etc. So what’s the solution? Buddha said we can make ourselves immune to heartbreak by eradicating or at least detaching ourselves from desire, but that is not an option for me. Even if I could, I wouldn’t want to, because without desire we become inhuman. Hofstadter didn’t shake my faith in free will, but Howdy Doody did.

Then I rallied, reminding myself of my reasons for believing in free will.[8] For starters, free will underpins our ethics and morality. It forces us to take responsibility for ourselves rather than consigning our fate to our genes or a divine plan. To have free will means to have choices, and choices, freely made, are what make life meaningful. Try telling a man locked in solitary confinement or a soldier who had his legs blown off that choices are illusory. “Let’s change places,” they might respond, “since you have nothing to lose.”

Yes, my choices are constrained, by the laws of physics, my genetic inheritance, upbringing and education, the social, cultural, political, and intellectual context of my existence. Also, I didn't choose to be born into this universe, to my parents, in this nation, in this era, and I don’t choose to grow old and die. But just because my choices are limited doesn't mean they don't exist. Just because I don't have absolute freedom doesn't mean I have none. Saying free will doesn't exist because it isn't absolutely free is like saying truth doesn't exist because we can't achieve absolute, perfect knowledge.

Free-will deniers contend that all causes are ultimately physical, and that to hold otherwise puts you in the company of believers in souls, ghosts, gods and other supernatural nonsense. But our minds, while subject to physical laws, are influenced by non-physical factors, including ideas produced by other minds, that alter the trajectory of our bodies through the world. Hofstadter’s loopy ideas nudged me onto the path of science writing in the early 1980s, and they drew me to Bloomington, Indiana, in the winter of 2016. That’s reason enough for me to believe in free will.

Listen to Hofstadter talk about beauty in his home in Bloomington, Indiana, March 18, 2016.

Notes

[1] I’m fascinated by recursion too, although “fascinated” is perhaps too benign a term. When I was nine or ten, I became struck by the oddity of thinking about thinking. I would think, “I’m thinking about thinking about thinking about thinking…” The sequence amused me at first, then it tormented me, because I couldn’t stop thinking about thinking about thinking… It was like an earworm, a song I couldn’t get out of my head. (In the early 1970s the whiny Rolling Stones song “Angie” played in my head for months. Sheer torture.) At first I would literally think the words, “thinking about thinking about thinking…” Then I abstracted it to the basic idea, this thing I couldn’t stop thinking about. It was like “The Zahir” of Borges, something that, once seen, cannot be forgotten. It would afflict me for hours. At some point I'd think happily, “Hey! I wasn’t thinking about the thing!” Then, “Oh no!” And it would start all over again.

[2] Hofstadter’s riff on how we leave traces of ourselves behind made me reflect on my obsessive digital behavior. Many times a day, I check my three email accounts plus Twitter and Facebook. A little less often I check my money-related accounts and my comments and traffic stats for my blog, and I also self-Google. By the time I’m done it’s time to start over. Somebody could have sent me another email or said something mean about me! So I have two selves. One is this Physical Self, bounded by a sack of skin, sitting here on a couch alone. The other is my unbounded Digital Self, which is out there even now mingling with the world, ranting and being ranted at, swapping flattery, witticisms and pomposities, accruing traffic and comments, or not, making or losing money. Digital Self should be a mere extension of Physical Self, but sometimes I fear the hierarchy has flipped. Physical Self is a slave, existing merely to serve Digital Self. Physical Self is not consoled at the thought that, after it dies, Digital Self will endure.

[3] I once had a file in which I jotted down examples of twisty things. Here are a few: Trying to meditate without thinking about the fact that I am meditating. Waking up at night in a house with no power and needing a flashlight to find a flashlight. Needing glasses to find glasses. Needing gas to get to a gas station. Writing about writing, reading about reading, scientifically studying science, philosophizing about philosophy, being skeptical about skepticism. I thought about this last example while writing Rational Mysticism. I began regarding my skepticism as a spiritual practice, which clears the mind of garbage, until my handling of actual garbage gave me pause. I use plastic garbage bags that come in a box. After I yank the last bag from the box, the box becomes trash, which I put in the bag. I sensed a riddle in the ritual, and eventually I got it: Every garbage-removal system generates garbage, and that includes skepticism and meditation.

[4] Daniel Dennett, who shares Hofstadter’s view of consciousness as an illusion, defended that position in his 2017 book From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds. Dennett gets huffy when accused of claiming that consciousness does not exist. He claims, rather, that consciousness is so insignificant, especially compared to our exalted notions of it, that it might as well not exist. Dennett's articulation of this position, unlike Hofstadter's, annoys me. After much conscious deliberation, I chose to criticize Dennett's stance in a blog post, “Is Consciousness Real?” Another perhaps more effective response would have been hurling one of Dennett’s own books at him.

[5] I mention Virginia Woolf so I can insert this note on a strikingly loopy passage in her stream-of-consciousness work The Waves. Rhoda, Woolf’s alter ego, is in a math class, staring at a problem written on the blackboard by the teacher, and she thinks: “Now the terror is beginning. . . . What is the answer? . . . I see only figures. The others are handing in their answers, one by one. Now it is my turn. But I have no answer. . . . I am left alone to find an answer. The figures mean nothing to me. Meaning has gone. . . . Look, the loop of the figure is beginning to fill with time; it holds the world in it. I begin to draw a figure and the world is looped in it, and I myself am outside the loop; which I now join – so – and seal up, and make entire. The world is entire, and I am outside of it, crying, ‘Oh, save me, from being blown for ever outside the loop of time!’"

[6] I describe this trip in The End of Science, Rational Mysticism and a blog post, “What Should We Do with Our Visions of Heaven and Hell?”

[7] The artist was Jordan Wolfson, the exhibit “Colored sculpture” and the gallery David Zwirner. In an interview, Wolfson says he based the marionette on Huckleberry Finn and Alfred E. Neuman as well as Howdy Doody.

[8] I have cited these reasons in posts such as “Will This Post Make Sam Harris Change His Mind About Free Will?” and “Why New Year Resolutionaries Should Believe in Free Will.”

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

The Weirdness

CHAPTER ONE

The Neuroscientist: Beyond the Brain

CHAPTER TWO

The Cognitive Scientist: Strange Loops All the Way Down

CHAPTER THREE

The Child Psychologist: The Hedgehog in the Garden

CHAPTER FOUR

The Complexologist: Tragedy and Telepathy

CHAPTER FIVE

The Freudian Lawyer: The Meaning of Madness

CHAPTER SIX

The Philosopher: Bullet Proof

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Novelist: Gladsadness

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Evolutionary Biologist: He-Town

CHAPTER NINE

The Economist: A Pretty Good Utopia

WRAP-UP

So What?