CHAPTER SIX

The Philosopher

Bullet Proof

In 2016 I joined a philosophy salon in New York City. Most of the participants have academic training in philosophy, and some are actual, full-time, professional philosophers. Roughly once a month, seven or eight of us meet in the salon-runner’s apartment to munch chocolate biscuits, sip wine and argue about a paper. Whatever the topic—the vagueness of knowledge, Wittgenstein’s mysticism, the dubiousness of moral rules—we often end up bickering about what philosophy is, or should be. What is its purpose? Its point?

In one session we considered “Why Isn’t There More Progress in Philosophy?” by David Chalmers. Chalmers is almost comically passive-aggressive in the paper, veering between defiance and doubt. He opens by declaring that “obviously” philosophy achieves some progress, but the rest of his paper undercuts that modest assertion. Science and philosophy have different methods and results, Chalmers notes. The former consists primarily of empirical investigations, the latter of argumentation. Science has turned out to be a much more potent method of generating truth. Whereas scientists converge on answers to questions, “there has not been large collective convergence to the truth on the big questions of philosophy.”

A survey of philosophers carried out by Chalmers and a colleague revealed deep divisions on big questions: What is the relationship between mind and body? How do we know about the external world? Does God exist? Do we have free will? Where does morality come from? Philosophers’ attempts to answer such questions, Chalmers remarks, “typically lead not to agreement but to sophisticated disagreement.” That is, progress consists less in defending truth claims than in casting doubt on them. Chalmers calls this “negative progress.”

Chalmers tries to stay upbeat. He insists that just because philosophers haven’t solved any major problems yet doesn’t mean they should stop trying. They should keep doing their best “to come up with those new insights, methods and concepts that might finally lead us to answering the questions.” This is an expression of faith. Like a valiant officer, Chalmers is exhorting his troops to keep charging forward when even he suspects the battle is unwinnable.

As if to prove Chalmers’s point about philosophy’s lack of convergence, the salon bickered bitterly over his paper. Members disagreed over his claim that methods of argumentation have improved. One was struck, reading papers from the 1960s and 1970s, by how poorly reasoned they were. Another had precisely the opposite reaction to older papers, they seemed smarter than newer ones. As the conversation unraveled, my mates seemed increasingly glum, with good reason. If philosophers can’t agree on anything after millennia of arguing, why bother?

After this session, I wrote a series of blog posts that asked: What is philosophy’s point? Sure, it can be fun, especially if you get paid to do it, but if it cannot tell us what is or ought to be, what good is it? Philosophy does the most good, I proposed, when it counters our terrible desire for certitude. Playing off Chalmers’s phrase “negative progress,” I called the kind of doubtful inquiry I had in mind negative philosophy. I also meant to evoke “negative theology,” which describes God as indescribable. After posting these thoughts on my blog, I waited for philosophers’ effusions of gratitude to come gushing in.[1]

* * * * *

Owen Flanagan, when we first met, struck me as unusually sensible, and genial, for a philosopher. It was 1994, and we were both at the big consciousness shindig in Tucson (the same one where I first saw Koch speak). We spoke on a sun-drenched patio outside the conference center, water splashing in a nearby circular fountain. Flanagan had coined the term “mysterian” to describe those who claim consciousness will never be cracked. The term was inspired by the 60s rock group Question Mark and the Mysterians, authors of the hit song “96 Tears.”

Flanagan was not a mysterian. He thought we could understand the conscious mind by studying it from the inside as well as outside, supplementing objective investigations of brains, minds and behavior with “phenomenology.” That is philosopher-speak for the study of subjective experience.

I liked Flanagan’s approach to mind, and I liked Flanagan, maybe because we have similar backgrounds. We both came from Irish Catholic families in New York City suburbs. Making small talk, we discovered that his wife Joyce and I grew up in the same Connecticut town, and I knew her family slightly.

Flanagan is a big-picture philosopher, who has written a dozen books on consciousness, morality and the meaning of life. My favorite is The Problem of the Soul, which he intended for non-philosophers. In an autobiographical section, he traces his philosophical obsessions to his religious upbringing. By the time he was seven or eight, he was beginning to think that the Church’s moral rules were nutty. If he has a sinful thought about a girl and a car runs him over before he confesses to a priest, God will torture him eternally? That can’t be right.

After he lost his faith, Flanagan remained fascinated by morality. Where does it come from? How do we decide what’s right and wrong? On the first day of his first college philosophy course, his professor said, “Plato posits the Good.” “I did not know what ‘posited’ was,” Flanagan recalls, “and I had never heard the definite article stand before the word ‘Good’—which I rightly heard as capitalized. But I was thrilled, captivated and hooked.”

Science became Flanagan’s polestar. It hasn’t explained everything, he acknowledges in Problem of the Soul, not by a long shot, but it has explained enough to validate materialism. Everything in the universe, including us, consists of physical stuff ruled by physical forces. God didn’t design us, natural selection did. We are animated meat, and when we die we die, that’s it.

That doesn’t mean there is no morality or meaning. Yes, natural selection made us innately selfish, but it also made us loving, compassionate, empathetic and concerned with fairness, because these tendencies helped our ancestors pass on their genes. If you define morality as caring for others, we are innately moral. Reason, Flanagan says, can refine and reinforce our moral instincts. It can help us see that our wellbeing depends not only on the wellbeing of our immediate kin, who carry our genes, but of all humans and even all of nature.

If you abandon belief in God and heaven, Flanagan says, you still have a lot to live for, like love, family, friendship, beauty and the chance to make the world a better place. You can live a good, meaningful life. But “if you want more,” Flanagan warns, “if you wish that your life had prospects for transcendent meaning, for more than the personal satisfaction and contentment you can achieve while you are still alive, and more than what you will have contributed to the well-being of this world after you die, then you are still in the grip of an illusion. Trust me, you can’t get more.”

And you do trust Flanagan, because he doesn’t browbeat you the way some hard-core atheists do. He comes across as humane, modest, down-to-earth. Sensible. And yet when The Problem of the Soul was published in 2002, Flanagan’s life was a mess. He was struggling with his own private problem of the soul.

That same year, we both attended a workshop on evolution and the meaning of life at Esalen, a neo-hippy resort in California. I asked Flanagan about his wife, Joyce, just to make conversation, and he said they had split up. I expressed the obligatory sympathy. I don’t recall prying for details, but Flanagan said a brain tumor, combined with medications, had affected his behavior in ways that undermined his marriage. Here is how I recall reacting:

A philosopher who specializes in mind and morality gets a brain tumor that makes him behave badly! Owen, this is fantastic material! You can be your own experimental subject! You can write about the mind-body problem from first-person and third-person perspectives! Think of what you can do with free will! You can get into whether the end of your marriage was your fault, or your tumor’s fault!

Flanagan, who fortunately is an easy-going, twinkle-in-the-eye kind of guy, smiled and shook his head in response to my outburst. The “material” was still too raw, he said, and writing about it now might hurt his ex-wife and children. Maybe someday.

When I came up with the idea for this book, I immediately remembered Flanagan. I called him and told him about my project. I asked if he was ready to talk, on the record, about his brain tumor, divorce and other troubles, and how they might have affected his views of the mind-body problem. Yes, he said, he was ready. I flew to North Carolina to talk to him a few months later. I thought Flanagan would be the easiest of my subjects to write about, but he turned out to be one of the hardest. Whenever I thought I had him figured out, I spotted a contradiction or omission in my understanding. It was almost as though I were trying to figure out myself.

* * * * *

Flanagan, who has taught at Duke for decades, picked me up at the Raleigh-Durham airport on a chilly winter day. He was dressed with the shabby gentility of an academic. Jeans, sneakers, down vest over a sweater. He had a goatish, gray-ginger beard, and hair that floated like mist above his head. We chatted about our divorces and kids as we headed to the National Humanities Center, just a few miles from Duke. Flanagan was in the middle of a year-long sabbatical at the center. He was trying to finish his magnum opus, a work charting the many varieties of morality.

The Humanities Center, white and otherworldly, looks like a spaceship that crash-landed in a Carolina pine grove. Flanagan led me to a table in an airy atrium/dining area ringed by skylights, conference rooms and offices. He was raised Catholic, so he is trained in the arts of guilt and confession. But as we sat across from each other—my recorder, red light gleaming ominously, on the table between us—he seemed nervous. When I asked if he preferred someplace more private, he shook his head. No, this spot is fine, he’s just gathering his thoughts.

To ease him into the interview, I reminded him of the story he told me in 2002 about his brain tumor. Perhaps we should start with that. As I spoke, Flanagan kept repeating or finishing my phrases. “Story,” “tumor,” “start with that.” A symptom of empathy, impatience, anxiety, all the above. For years, he was reluctant to tell his story, because he didn't want to hurt his family. “As I get further and further along, I’m able to tell it.”

But first he needed to give me a little background. Catholicism was one important part of his upbringing. Another was drinking. His father, who headed a successful accounting firm in New York City, “would come home every night and drink his white drinks, his cocktails. When I was 18, he taught me how to make a martini.” Owen and his five siblings grew up to be heavy drinkers.

He realized he had a problem as early as 1981, when he was teaching at Wellesley College, and his first child, Ben, was born. When he first saw Ben in the hospital, Flanagan felt overwhelming love. Eating dinner that night with his parents, who had come to town for the delivery, he looked at his mother and thought, “Holy shit! You felt towards me the way I feel towards Ben!”

Flanagan and his son Ben, 1981.

He spent the next day with his wife and parents in the hospital. “I’m in the zone of one of life’s greatest goods, which everyone says is a certifiably great human experience that you should love and treasure,” he recalled. But toward evening he wanted a drink, and he became annoyed that he couldn't easily slip away to get it. His son’s birth had become “a fucking inconvenience.” He had enough self-awareness to be appalled at himself. Did he get the drink? Yes, Flanagan nodded, he got the drink.

In 1987, his youngest brother, who had been drinking, died in a solo driving accident. Flanagan identified the body in a morgue. Shaken, he gave up alcohol for the sake of his children. Six years later, he was still sober, and life was good. He had a solid marriage and two great kids. He was teaching at a prestigious college, building his reputation as a philosopher. Then, shortly before he moved from Wellesley to Duke, something strange happened.

“One day I woke up and there were no longer any sexual qualia in the world,” Flanagan said. Qualia is philosophical jargon for subjective sensations. It wasn’t just that Flanagan didn't feel horny. He could scarcely remember what it was like to be horny. Normally, his sexual response was determined by the external stimulus—this woman attracts him, that one doesn’t—but now stimulus was irrelevant. Lust was an alien concept. “It was like if color vision disappeared,” he said. “The world was asexual to me.”[2]

Alarmed, he saw a doctor, who pressed him on how he felt. Flanagan replied: Imagine you are lying on a bed in a hotel room watching the news on television, and Marilyn Monroe, at her most luscious, walks into the room and begs you to make love to her. You would tell her to move, because she is blocking the television.

Normally lean, Flanagan had gained weight, although he hadn’t changed his diet and ran almost every day. Blood tests revealed that his testosterone was extremely low and prolactin extremely high. Prolactin is a hormone that, in excess, suppresses libido. An MRI scan confirmed the physician’s suspicion: Flanagan had a prolactinoma, a benign pituitary tumor that suppresses testosterone and elevates prolactin. Most such tumors are asymptomatic, but they can cause weight gain and loss of libido, Flanagan’s symptoms.

Although he lacked sexual desire, Flanagan had the desire for desire. He wanted his libido back, for the sake of his marriage, if nothing else. Surgery was too risky, because it “could turn you into a hormonal disaster.” The doctors prescribed Dostinex, a drug that keeps the pituitary gland from producing prolactin, and a testosterone gel that he rubbed on his upper back.

His hormone levels gradually returned to normal, and the tumor stopped growing. Flanagan and his wife resumed sexual relations, but his desire remained low, and he felt anxious and depressed. “I was scared of dying,” he said. “I was scared because I didn’t think I had enough money saved up to put Ben and Kate through college. I was scared about my relationship with Joyce.”

He saw a psychiatrist, who put him on the anti-anxiety drug Klonopin and the trendy new antidepressant Prozac. Flanagan had discussed Prozac’s philosophical implications in a public event with psychiatrist Peter Kramer. In his 1993 bestseller Listening to Prozac, Kramer claimed that Prozac could make patients “better than well.” Actually, the drug was no more effective than older antidepressants, and it suppressed libido.[3]

When Flanagan’s sexual problems persisted, a psychiatrist in North Carolina, to which he had moved, put him on another antidepressant, Wellbutrin, to “jumpstart” his libido. Flanagan learned later that this prescription was a mistake. Taking Wellbutrin on top of Prozac is now “completely prohibited, because it produces exactly the effect it produced in me.”

After a week on Wellbutrin, Flanagan started to feel good. Very good. He went to a book-launch party at Duke, at which champagne was served. At that point, Flanagan had been sober for seven years. “If you asked me then if Owen Flanagan would take another drink, I would say, ‘Absolutely not, he has no interest in drinking.’” But when someone handed Flanagan a glass of champagne, he drank it without hesitation.

Flanagan became entranced by a young female editor at the party. “She looked like the most beautiful woman in the world, and I wanted her.” By the end of the day, Flanagan had begun an affair with her. Over the next 10 days, he became obsessed with high-end cars, toward which he had previously been indifferent. He started visiting Mercedes, BMW and Jaguar dealerships. “They would lend me cars for weekends or overnight, so I could ride them around.” After buying a BMW, he bought a house, a rental property. One day he became so obsessed by the actor Andy Griffith that he drove to his childhood home in Mount Airy, North Carolina. Meanwhile he kept drinking and seeing his lover.

Telling me all this, Flanagan was cool, just reporting the facts. I asked how he felt emotionally during this period. “I was bullet proof,” he said. “On top of the world.” His libido had come roaring back. His lover, the editor, lived with another man, and Flanagan enjoyed trysts at her house. “I loved the danger.”

He kept performing his academic, spousal and parental duties as if nothing had changed, even as he pursued his new projects. “I’m signing papers, I’m moving $40,000 to buy this cheap house.” Now and then, for example while driving to see Andy Griffith’s home, Flanagan realized “there might be something a little bit wrong.” For the most part he was clueless. “I just lost a layer of self-knowledge, because it didn’t seem abnormal."

Flanagan squirmed in his chair, as though debating whether to tell me something. He said that during his “bullet proof” period, he told his wife about his affair and blamed it on her. He was having sex with another woman because she, Joyce, bored him. “It didn’t seem wrong to me to say that,” Flanagan said to me, his voice eerily bland. “My reflective moral self just seemed to evaporate.” The moral philosopher had lost his sense of right and wrong.

Flanagan was planning to go to Australia, where he would be a visiting scholar. His wife had planned to accompany him with their son and daughter, but she decided they would stay behind. After Flanagan arrived in Australia, he stopped taking Wellbutrin, which he suspected of causing his abnormal behavior. Gradually he realized “the gravity of the harm” he had done to his wife.

Telling me all this, Flanagan’s discomfort was evident. We had moved to his office now. He sat in a chair behind his desk, and he kept shifting in his seat. He said he felt hot. Was I hot? I was fine, I said.[4] After sipping from a water bottle, Flanagan resumed his story. When he returned from Australia, Joyce took him back. She accepted that medications had triggered his affair, which was over. “She’s a forgiving person,” Flanagan said.

The problem was, he couldn’t stop drinking. On many mornings he woke up vowing never to drink again, and within an hour he would swallow three 16-ounce beers to steady his nerves. Throughout the day he would “maintenance dose.” He had another affair, and this time his marriage ended. Joyce moved to Maine. They remain friends. “I think neither Joyce or I are constitutionally people who hold grudges.”

He went to Alcoholics Anonymous, on and off, and quit drinking, on and off. He kept drinking even after being jailed for driving drunk. “The problem isn’t stopping, it’s staying stopped. I couldn’t stay stopped.” I had mentioned to Flanagan that I quit drinking when my marriage ended. He asked how hard it was for me. Did I experience withdrawal? The “heebie jeebies”? No? Well, he did. He went through detox five times. He craved booze so much that he ruled out suicide, because he couldn’t drink if he was dead. Flanagan smiled when he said this, but he wasn’t kidding.

He stopped drinking in 2007, more than a dozen years after the glass of champagne at the book-launch party. Does he ever crave a drink now? No, Flanagan replied, but he didn’t crave one before he had that glass of champagne at the book party. “I’m more diligent now,” he said.

* * * * *

As Flanagan told me about his tribulations, I felt uneasy. If there is such a thing as smiling Irish eyes, Flanagan has them, plus dimples that deepen when he grins, which is often. He wants you to like him, and he succeeds. He’s charming not in an overbearing, alpha-male way, but in a light-hearted, life-of-the-party, liked-by-all-the-gals-and-guys way. Life’s not so bad, his personality implies. Let’s enjoy it, enjoy each other, as best we can.

A darker self peeks through now and then. Flanagan has a habit, almost a nervous tic, of offsetting compliments—of others and of himself—with criticism, and vice versa. Consider how he described Joyce, his ex-wife, early in our conversation. “Joyce was a very reserved—wonderful human being—reserved, shy person. And I like them high heels and low maintenance.” Chuckle. “She was definitely low maintenance, in that she definitely wasn’t a complainer. But once in a while I would drink to excess, and she would complain about it.”

Note Flanagan’s insertion of “wonderful human being” into his description of his ex-wife as “reserved,” which comes close to “dull.” His wife “wasn’t a complainer,” except when she was. With the “high heels and low maintenance” line, Flanagan was mocking his sexual shallowness, but bragging too.

Mulling over how Flanagan combines strokes with jabs, I realized we share this trait. I’m a judgmental jerk who likes to be liked, so I disguise my criticism of others with irony or humor. Very passive-aggressive. And like Flanagan, I puff myself up and deflate myself, sometimes simultaneously.

Flanagan and I have other things in common. We’re “aging hippies” (his phrase), lapsed Catholics and ex-drinkers with a taste for philosophizing. There are differences between us. I am more agnostic about supernatural matters than Flanagan, perhaps because psychedelics have loosened my grip on reality. I don’t believe in God, ghosts or souls, but I’m not adamant in my disbelief.

Another difference is that I’m not nearly as charming as Flanagan. That’s not modesty, just a fact. At the Humanities Center, Flanagan bantered gracefully with a receptionist, cafeteria workers and several other scholars. Later, he charmed baristas, mechanics and a waitress at a cafe, auto-repair shop and restaurant. I could no more duplicate his performance than I could walk on my hands.

Flanagan’s social skill makes him a little self-conscious. In Problem of the Soul, he notes that many people perceive him as “lively and outgoing, even charismatic.” But this, he suggests, is not his true self. Deep inside “there remains a very shy, somewhat withdrawn person.” Flanagan is trying to tell us, and perhaps himself, who he really is. He is the shy guy, not the “charismatic” guy. He is the good Catholic boy, who isn’t mean to innocent people.

But surely Flanagan sometimes wonders who he really is. Natural selection designed male primates for one purpose, spreading their seed. Maybe the true self of all men is beastly Mr. Hyde, not civilized Dr. Jekyll, and we are all brainwashed into being good by parents, nuns, priests, teachers. Maybe if we had no fear of social disapproval and punishment, we’d be really bad.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. One of my goals, while interviewing Flanagan, was to determine how, or whether, his professional training helped him cope with his personal trials. Did philosophy do him any good? If not, what is its point? I have come up with five ways in which his mind-body expertise might have served him. I call them “Self-Mastery,” “The Buddhism Gambit,” “My Tumor Did It,” “What Moral Rules?” and “Going Meta.” Below I consider them one by one.

Self-Mastery

Self-mastery was the original point of philosophy. As Socrates said, “examining myself and others is the greatest good.” Socrates, Confucius and other ancient sages assumed that thinking hard about what is right and wrong will help you achieve self-knowledge and self-control and become a better, wiser person.

Philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel and a colleague recently tested this claim by examining the behavior of philosophers who specialize in ethics. They included self-reported data from philosophers as well as information from historical archives. Behaviors included staying in touch with your mother, responding to student emails, talking during someone else’s lecture, voting, meat-eating, blood donation and joining the Nazi party. The last category was a swipe at Martin Heidegger. None of the questions addressed adultery, unfortunately.

Schwitzgebel and his colleague found that ethicists are ethically “indistinguishable” from other professors. Ruminating over these findings, Schwitzgebel expresses disappointment with moral philosophers, including himself. He notes that he and his colleagues see ethics as a set of “abstract problems” with “no bearing on day-to-day life.” If ethicists draw upon their training, they do so to justify dubious actions. They “excel at rationalization and excuse-making.”

None of this was news to Flanagan. When I asked if philosophers’ expertise makes them wiser, he shook his head before I completed the question. “Absolutely not,” he said. “Academics—philosophers, let’s just say—are more ill-formed than your average person.” Smiling, he told me a joke. How can you tell the difference between a philosopher and a mathematician? The philosopher looks at your shoes when he’s speaking to you. I looked puzzled, and Flanagan explained that mathematicians look at their own shoes while speaking to you.[5]

The Buddhism Gambit

Buddhism is one of the oldest methods of self-mastery. Flanagan became interested in Buddhism in college, and in 1991 he participated in a meeting with the Dalai Lama and other Buddhists in India. He was intrigued by their claim that meditation helps control anger and other negative emotions.

Flanagan has meditated for decades, because it makes him feel good. “I’ve done a lot of meditating,” he told me. “I’m actually skillful at some of it.” He was fascinated by research on how meditation can alter your brain and mood and potentially make you very happy. But he accused some meditation researchers of being “snake-oil salesmen” who exaggerate its benefits. Meditation is far from a panacea. For a dozen years, it couldn’t save Flanagan from himself.

Although Flanagan prefers it to Catholicism, the religion in which he was raised, he can be quite critical of Buddhism. When I asked if he believes in enlightenment, the state of supreme wisdom and bliss that Buddha and other sages supposedly achieved, Flanagan grimaced. I might as well have asked if he believes in Bigfoot.

In his book The Really Hard Problem, Flanagan describes Buddhist methods for cultivating compassion as “brainwashing.” In The Bodhisattva’s Brain he remarks that “many western Buddhists I know are not very nice, both more passive-aggressive and more narcissistic than other types I prefer.” I circled this passage and wrote “Yes!!!” in the margin. I’ve always felt that the link between meditation and morality is overrated.[6]

My Tumor Did It

If Flanagan couldn’t stop himself from behaving badly, his expertise in the mind-body problem could at least have suppressed his guilt. An advantage of this option is that it can be applied retroactively.

Flanagan’s life dramatizes biology’s power over us. He could justifiably assert that when he misbehaved, he was not himself. He was under the influence of a brain tumor, medications and a genetic predisposition to alcoholism. Clearly he wasn’t himself when he was cruel to his wife, any more than when he bought the BMW or drove to Andy Griffith’s birthplace. None of this was his fault. He didn’t possess sufficient free will. Chemistry trumps morality.

In Problem of the Soul Flanagan notes that the concept of free will assumes we have self-knowledge and hence control over our actions. This assumption is at odds with what science and common sense tell us. We are animals, physical creatures ruled by a host of biological and environmental forces. We can know ourselves only dimly, at best.

But Flanagan does not let himself off the hook. He rejects hard-core determinism. Just because we cannot achieve complete self-knowledge and self-control doesn’t mean we can’t achieve any. Flanagan believes in choices, self-control, moral responsibility. And alcoholism isn’t like cystic fibrosis, a disease over which we have no control, or even schizophrenia.

Flanagan also denies that the self is nothing but an illusion. That position, he argues, leads to absurdities, such as elimination of distinctions between novels and biographies, or between lies and honesty. He notes that an alcoholic often lies to others and to himself about his drinking. “This would not matter if the self were entirely fictional,” Flanagan comments drily, “but it obviously does matter.”

What Moral Rules?

Flanagan could have rationalized away his guilt by arguing that there are no absolute moral rules. For example, when he told his wife he cheated on her because she bored him, he was being honest, and honesty, you could argue, trumps kindness. No less an authority than Kant contended that lying is never ethical.

Other philosophical big shots assert that all our notions of right and wrong are petty bullshit. They advocate a kind of moral nihilism, in which there is no good or evil, anything goes. “There are absolutely no moral facts,” Nietzsche declares in Twilight of the Idols. “What moral and religious judgments have in common is belief in things that aren’t real.”[7]

Buddhism has a strain of moral nihilism too, as Flanagan has pointed out. Buddhism’s doctrine of impermanence is consistent with a life of pure pleasure-seeking. That explains why some legendary Buddhist sages flout conventional moral rules. They get drunk, seduce other men’s women, fight, even kill. So why should Flanagan feel bad about screwing around and saying mean things to his wife? From the vantage of infinity and eternity, his worst sins vanish into insignificance. Nothing matters.

And yet Flanagan does not, cannot, take advantage of these philosophical excuses. He knows that right and wrong exist, even if philosophy can’t define them in absolute terms. Perhaps Gödel’s incompleteness theorem has an ethical corollary: Even if we can’t prove it, we know in our hearts that some acts are wrong, and we feel shame.

Going Meta

Going meta means looking at your own experiences objectively, as material for intellectual analysis. You stand back and think, Hmm, interesting. Going meta has helped me deal with painful episodes in my life, like depression and divorce.

Flanagan has advocated a meta-ish approach to the hard problem. Scientists should combine objective studies of brains and minds with phenomenology, the exploration of subjective experience. Oliver Sacks employed this method in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and other books, which tell the tales of people afflicted by strokes, tumors and other disorders. Flanagan’s pituitary tumor turned him into his own neurological case study: The Man Who Lost His Libido, Found It Again and Became an Andy Griffith Fan.

But Flanagan had a hard time seeing his troubles objectively. When his brain tumor deleted his libido, part of him found his symptoms interesting, at first. But he couldn’t simply stand back and think, Cool phenomenology! He wasn’t an expert on consciousness learning what it feels like to have a brain tumor. He was a man, a husband and father who was frightened and depressed. Ultimately he might as well have been a plumber as a philosopher.

The same was true of his ethical struggles. When he felt irritated that his son’s birth was making it hard to get a drink, he couldn’t marvel, like Walt Whitman, at his multitudinous selves. He couldn’t look at himself as The Man Who Loved Booze More Than His Wife and Newborn Son. He was ashamed, not fascinated, because his behavior was “ugly and weird.” He felt shame later, too, when his drinking and philandering brought an end to his marriage.

Catholicism is criticized, justly, for excessive shaming, especially when it comes to sexual behavior that violates Church rules, like homosexuality and pre-marital sex. But shame can be “an appropriate thing to feel,” Flanagan said, if it motivates you to behave better. Flanagan defined shame as “feeling like a bad person, not the person you want to be.”

Flanagan cannot shake his shame for his cruelty toward his ex-wife, especially when he blamed her for his cheating. This, of all his misdeeds, seemed to haunt him most. “There is this person,” he said, “a good Catholic boy, who still believes, and always did believe, you shouldn’t hurt people, especially good people, who don’t fuck you over.”

Philosophy didn’t save Flanagan’s marriage or, for years, help him stay off booze. It couldn’t help him achieve self-mastery, or relieve him of guilt. But it still did Flanagan a lot of good. Throughout his ordeals, he kept philosophizing, thinking, talking, teaching, reading about the mind-body problem. He wrote five books during his troubles! Without philosophy, who knows? Flanagan might still be drinking, or dead. Writing about how life has no transcendent meaning gave his life meaning.

* * * * *

After confessing his sins, Flanagan seemed to relax, like a man with a root canal behind him. We chatted about consciousness, the mystery that first brought us together back in 1994. Flanagan remained confident that science will solve the hard problem. “I am very anti-mysterian,” he said. There is “some kind of explanation to be given.” After science has explained consciousness in physiological terms, he said, people might stop seeing consciousness as weird.

That outcome, I confessed, would disappoint me. In fact, I hoped philosophers would point out the inadequacies of all explanations, so consciousness remains weird. Flanagan smiled. He agreed that philosophy can provide a service by reminding us “how amazing and bewildering the whole fucking thing is.” He fluttered his hands around his head. That his brain, he said, produces “the amazing Technicolor aspects of experience, my love, my hates, my worries, my anxieties, my aspirations, the whole… It’s unbelievable!”

Flanagan still has dark moments. Although he insists that a scientific, materialistic worldview need not be “disenchanting,” he feels disenchanted now and then. “I think, Fuck it, rage at the universe.” But for the most part he feels pretty good, physically and mentally. He is sober, and happily re-married. He still has the pituitary-gland tumor. He treats it by popping a pill and rubbing testosterone gel on his pelt every day. “I am a performance-enhanced philosopher,” he said.

He has become calmer and more patient, perhaps because he’s older. “The flames of passion and desire burn less brightly,” he said. He thought of himself as “a reasonably worthy human project that didn’t fuck up the world.” He had made “a little, tiny contribution” to the philosophy of mind, morality and meaning, “and that feels good.”

Smiling proudly, he pointed at a big stack of paper on a table beside me. It was his new book, The Geography of Morals, which seeks common ground between diverse moral perspectives. It combines insights provided by evolutionary psychology and other fields with cross-cultural comparisons of moral customs. “I love seeing the way other people have put together meaningful lives.”

Writing the book helped him figure out what really matters to him. “Nothing deep, existentially, but what are the most important things?” He settled on a few simple components of a good, meaningful life. They include “friendship, love, good relations,” “being there for friends and loved ones,” “having some integrity,” “knowing some stuff” and “not being a dick.”

When we left the Humanities Center, Flanagan drove us to his favorite café for espresso. Later we walked around a park adjoining the Duke campus. As young women jogged past us, glistening with sweat, we gossiped about prominent intellectuals mired in sexual scandal, yet more evidence, as if it were needed, that erudition does not inoculate you from foolishness.

Back at Flanagan’s house, I met his second wife, Lynn, and their three dogs. One dog kept pestering me to pet him by nudging me with his snout. Lynn was going through an identity crisis, trying to figure out what really mattered to her, and what she should do next. She had been in the restaurant business, and now she was working as a volunteer in an animal shelter, because she loved animals. She had brought these three dogs home from the shelter.

Flanagan had mentioned earlier that the dogs were complicating a planned move to Stanford, where he was going to be a visiting scholar. He didn’t josh Lynn the way he had other people we met that day. He treated her delicately, hesitantly. By the time he dropped me off at my hotel that night, I felt affection for him, too much for my purposes. I thought, How can I write about this man without being a dick?

I was still wrestling with this dilemma a year later when The Geography of Morals came out. Its big theme is that we shouldn’t blindly accept the morals drummed into us by our families and cultures. We should expand our sense of right and wrong by seeing it from as many points of view as possible, including science, philosophy, the arts and non-western cultures.

Flanagan accepts that evolution bequeathed us our morality, such as it is. The Good, far from existing in a Platonic realm, or in the mind of God, is just a product of our genes’ mindless compulsion to propagate. But he knocks Darwinians who suggest that socialism is doomed to fail because it runs counter to our selfish nature. Surely, he says, we can create a much better world—more fair, peaceful and free—than ours.

We should reject moral relativism, Flanagan writes, the idea that “Hitler wasn’t bad, just different.” But we should also resist the temptation to claim that our moral rules have the authority of scientific or mathematical truths. “The key move,” he writes, “is one of humility.” Humility does not come naturally to us, because natural selection designed our minds to “react quickly and decisively” in social situations. “This might make you feel cocky, confident and assured that you see things correctly,” Flanagan writes. “Doubt yourself,” he advises. The italics are mine.

Flanagan is an exemplar of the doubtful mode of inquiry that I call negative philosophy. His intellectual modesty, his constant hedging, his oscillation between praise and criticism, of himself and others, is a matter of style as well as substance. It is probably a congenital trait as much as the product of rational deliberation. He was “timid” as a child, he said, and his adult troubles have reinforced his acute sense of the limits of self-understanding.

Whatever the source of this quality, I admire it, and I wish there were more of it in the world. When I teach, I’m always telling my students, in one way or another, Doubt yourself. But doubt can only help us so much. If you see someone drowning, or if you are drowning yourself, doubt won’t do you much good. Flanagan’s life demonstrates that truth.

* * * * *

Owen Flanagan in Maine, 2018.

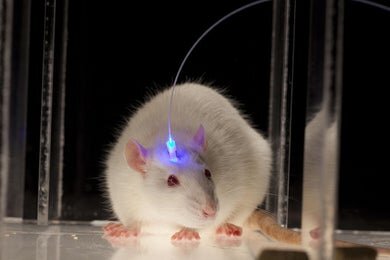

A few years before I started this book, I decided I had to write a novel, or try, before I die. I came up with a story that I titled The Optogenetic Bodhisattva. The hero is Eamon Poole, a young science writer living in New York City in the not-so-distant future. Eamon is afflicted with sweaty, heart-pounding panic attacks, which strike him with increasing frequency. Doctors can’t figure out what’s wrong with him, and the medications they prescribe do no good.

Desperate, Eamon turns to an underground brain hacker he has written about, Bjorn. He soups people up with optogenetic brain implants, which consist of viruses and micro-lasers. The viruses make the subject’s brain cells sensitive to light, so the micro-lasers can manipulate the brain and hence mood with pulses of light. Optogenetics is a real technology that enthusiasts think might someday eradicate mental illness. I doubt the therapeutic potential of optogenetics, but I love its metaphorical sheen.[8]

Bjorn tests a new implant on Eamon. It tweaks his genes in ways that boost secretion of dimethyl tryptamine, DMT, a psychedelic that occurs naturally in the brain (this is a real thing too). In a basement lab in Brooklyn, Bjorn knocks Eamon out and slips the optogenetic package over the top of his eyeballs and into his frontal cortex (again, transorbital brain surgery is an actual method). When Eamon wakes up, he feels really, really good, blissful, giddy. The boundary between himself and the rest of the world feels porous. When he looks into Bjorn’s eyes, streamers of light flow back and forth between them. Everything seems marvelous, amazing, Technicolor. He feels in his bones the improbability and absurdity of existence. He smiles constantly, laughs frequently. Eamon has achieved enlightenment, as I imagine it. My description of his state of mind is based on my readings of the mystical literature and psychedelic experiences.

Photo used to market optogenetics.

Fearlessness, I’ve always assumed, is a key component of enlightenment, so I made Eamon fearless. Just as Flanagan’s tumor deleted his libido, Eamon’s implant erased his fear. He cannot even remember what it was like to be afraid. Fearlessness gives him a kind of super-charged free will. He is still bound by the laws of nature, but within those physical boundaries he has infinite degrees of freedom. His radiant demeanor also makes him charismatic. Women and men are drawn to him.

So what does Eamon do, besides giving up science writing? (I love what I do, but no one would believe a story about a guy who can do anything and chooses to write about science.) Does he devote himself to helping others? Does he seek power, money, sexual conquest, all the above? Does he live alone in the woods, where he can contemplate the clear light of the abyss? Does he become a self-help guru? Run for President?

Eamon is exhilarated by his freedom, but I, his all-too-anxious creator, was confounded. Without fear, there can be no courage, without courage, no character. Self-doubt, shame, conscience are side effects of fear. So I thought. A life without fear is like a life without gravity or friction. It’s too free. Lacking the resistance of fear, your actions might become impulsive, random, bizarre. I couldn’t decide whether Eamon would be good, bad or just weird. I couldn’t figure out Eamon Poole, my fictional doppelganger, so I set aside The Optogenetic Bodhisattva.

Now I’m trying to figure out Owen Flanagan. In the mid-1990s, after he was diagnosed with a brain tumor, medications made Flanagan temporarily fearless. He felt “bullet proof.” He lost his conscience, his self-doubt. He started drinking and cheating on his wife, and he did impulsive, random, bizarre things, like buying a house and car he didn’t need and visiting the home of Andy Griffith.

Flanagan’s fear and conscience eventually returned. He quit drinking, renounced his wild ways, married again. Those were sensible things to do. If he hadn’t quit drinking, he might have ended up unemployed or dead. But what if he could have been sustainably, competently fearless? Maybe that life would have been a lot more fun.

Anyone who tracks the spirituality racket knows that many supposedly enlightened gurus resemble psychopaths. They are fearless, charismatic, amoral. Take Chogyam Trungpa, a Tibetan Buddhist llama who came to the west in the 1960s and became a popular guru. He wrote best-selling books on spirituality and founded the Naropa Institute. People I respect have assured me that he was the wisest person they have ever known, but he was a promiscuous drunk and bully who died in 1987 of liver disease.

Chogyam Trungpa

Some bad gurus are probably just con men taking advantage of spiritual seekers’ desperation and gullibility. Others, I suspect, are genuine mystics, who have gone super-meta, like Siddhartha, rising far above the hurly-burly of life and seeing it from the perspective of eternity. You can react to this mystical experience in two very different ways. You might see each individual creature as precious. You cherish all sentient things and yearn to ease their suffering. This is the path of the saint, savior, bodhisattva.

Or you might think, Nothing lasts, nothing matters. The suffering of everyone on earth, or everyone who has ever lived, is infinitesimal, compared to eternity. A human life has no more value or meaning than that of a cockroach. You don’t give a shit about the Holocaust, or Syrian kids blown to bits by American bombs, let alone one woman’s hurt feelings.

The cases of Eamon Poole and Owen Flanagan have helped me discover a contradiction in my philosophy. If I had to choose a supreme value, it would be freedom. Life has no meaning unless we are free to choose. Fearlessness should be desirable, too, because the more fearless we are, the more free we are. But fearlessness can turn us into psychopaths, who do not give a shit about anything but our own pleasure.

If you don’t fear death, the judgment of God or of other people, if you know—really know—that nothing matters, what, if anything, restrains you? What keeps you from hurting others? Reason? No, because reason confirms your mystical intuition that all things pass, there is no divine justice, nothing matters.

If reason can’t guide you, you’re left with your innate tendencies. If you have a strong tendency toward empathy and compassion, you become a good guru, a bodhisattva, who cares for others. If you have a strong innate desire for sex, power and high adventure, you become a bad guru, de Sade in a saffron robe. Your “choice” comes down to the genes your parents bequeathed you.

In one of his dialogues, Socrates argues with Glaucon about the true nature of men. Glaucon imagines a magic ring that makes men invisible, so they can do anything and get away with it. He asserts that men who found such a ring would be bad, really bad. They would kill other men and take their property and their women. Socrates says a wise man would resist such temptations, because true freedom means not being enslaved by your appetites.

I’m not so sure. I am a conventional, cowardly goody-goody. When I watch shows in which the hero is a criminal, like The Sopranos or Breaking Bad, I think, What a stressful life! I couldn’t live like that. But part of me envies the outlaws. I think, That would be true freedom. The rest of us are puppets, slaves of convention.

I sometimes wonder, What would it be like to be a psychopath, unencumbered by fear or compassion? What would it be like to be one of those crazy, charismatic gurus who drink and fuck with abandon and are worshipped for their holiness? If there is no God, and no Good, everything is permitted.

I’m not sure where this leaves me. I still think the world could use more freedom and less fear. But if we lose all our fear, we might lose our self-doubt, and become self-righteous dicks, or worse. We might lose our sense of wonder, because what is wonder but doubt with positive valance? One outcome of this rumination is that I no longer fantasize about a cure for fear, a neural or genetic tweak that makes us feel bullet proof, so fearless we cannot even remember what it was like to be afraid. I fear that if we lose our fear, we might become monsters. That might be who we really are.

Listen to Flanagan talk about the effects of his brain tumor, North Carolina, January 22, 2016.

Notes

[1] See “What Is Philosophy's Point?, Part 1 (Hint: It's Not Discovering Truth), “What is Philosophy's Point?, Part 2. Maybe It's a Martial Art,” “What Is Philosophy's Point?, Part 3. Maybe It Should Stick to Ethics,” “What Is Philosophy's Point?, Part 4. Maybe It's Poetry with No Rhyme and Lots of Reason,” and “What Is Philosophy’s Point?, Part 5. A Call for “Negative Philosophy."

[2] In his classic 1986 paper “What Mary Didn’t Know,” Frank Jackson writes about a woman, Mary, who is raised in a black and white room and can see the world only via a black and white television. Mary learns everything there is to know, scientifically, about colors, even though she has never perceived color. She has objective but not subjective knowledge. So what does she really know about color? Flanagan’s case made me imagine an experiment in which Mary can read or look at anything she likes about sex, including hard-core pornography, but she never interacts with another human being, male or female. What would Mary know about sex? Would she lack all sexual qualia, as Flanagan did in the early stages of his brain tumor? Or would she feel desire even in the absence of any external stimuli? My guess is that Mary would have sexual qualia of some kind, because the sexual instinct is more vital to human fitness than color perception. My view is based in part on occasions in which I had sex while experiencing severe psychedelic-induced derealization. To my conscious mind, the sex act seemed bizarre, but my body kept happily doing what natural selection programmed it to do.

[3] Peter Kramer’s claim that Prozac could make us “better than well” was always a fantasy. When his book was published in 1993, studies by Eli Lilly, Prozac's manufacturer, showed that it was no more effective than older antidepressants, such as tricyclic drugs, or psychotherapy. Although Prozac was touted for its relatively mild side effects, it causes sexual dysfunction in as many as three out of four consumers. Kramer relegated a discussion of Prozac's sexual side effects to the fine print, literally, in his book's endnotes. Long after Listening to Prozac was published, Kramer continued shilling for antidepressants. See for example his 2011 New York Times essay "In Defense of Antidepressants.” For a more critical perspective, see “Are Antidepressants Just Placebos with Side Effects?”, “Are Psychiatric Medications Making Us Sicker?” and “Meta-Post: Horgan Posts on Antidepressants, Brain Implants, Psychedelics, Meditation and Other Therapies for Mental Illness.”

[4] Flanagan’s question reminded me of a strange paper that we considered in my philosophy salon, “Cognitive Homelessness,” by Timothy Williamson. It features an elaborate argument, based on the so-called Sorites paradox, that you cannot know with certainty whether you are hot or not. The paradox dwells on the imprecision of language. If it is 100 degrees Fahrenheit in your room, you know you are hot. Reduce the temperature by one degree. Are you still hot? Of course you are, but keep reducing the temperature one degree at a time and at some indeterminate point you won’t feel hot any more. Williamson springs off the Sorites paradox, does a triple back flip and concludes: “Feeling hot does not imply being in a position to know that one is hot.” Williamson concludes that we are “cognitively homeless,” by which he means that “nothing of interest is inherently accessible” to our knowledge. Whoa. I wasn’t sure what Williamson’s aim was. A parody of philosophy? A demonstration that so-called rational analysis is futile, because if you’re sufficiently clever you can defend any wacky conclusion? The more I pondered the paper, the more I liked it. I began to see—or think I saw—the world through Williamson’s eyes. The view fascinated me, in part because it’s odd. The paper also seemed ironic in the literary sense, seething with possible meanings. Then, I had an epiphany: Philosophy is poetry with little rhyme and lots of reason. And by “poetry” I mean literature, music, film—all the arts. When I ran my reaction to Cognitive Homelessness by my salon mates, they didn’t exactly embrace it. One philosopher assured me that Williamson was definitely not being ironic in Cognitive Homelessness. Williamson was expressing himself as rigorously as he could, and he would be appalled to hear his paper likened to poetry. But how could my salon-mate know that?

[5] I wrote about Schwitzgebel’s research in “Is Self-Knowledge Overrated?” The column has quotes from Flanagan and other subjects of this book.

[6] For critical takes on meditation and Buddhism, see “Meta-Meditation: A Skeptic Meditates on Meditation,” “Can Buddhism Save Us?,” “Why I Don't Dig Buddhism,” “Research on TM and Other Forms of Meditation Stinks,” “Do All Cults, Like All Psychotherapies, Exploit the Placebo Effect?” and “Can Meditation Makes Us Nicer?”

[7] One session of my philosophy salon was dedicated to analyzing “Morality, the Peculiar Institution,” a chapter in the 1985 book Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy by Bernard Williams. He concludes that “we would be better off without” morality. Not that we should behave like sociopaths, but we should abandon the quest for a universal moral system, because any such system fails to do justice to the boundless complexity and contingency of life. Ironically, Williams’s writing is suffused with a humane, ethical sensibility.

[8] See my posts on optogenetics, “Why Optogenetic Methods for Manipulating Brains Don’t Light Me Up” and “Why Optogenetics Doesn’t Light Me Up: The Sequel.”

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

The Weirdness

CHAPTER ONE

The Neuroscientist: Beyond the Brain

CHAPTER TWO

The Cognitive Scientist: Strange Loops All the Way Down

CHAPTER THREE

The Child Psychologist: The Hedgehog in the Garden

CHAPTER FOUR

The Complexologist: Tragedy and Telepathy

CHAPTER FIVE

The Freudian Lawyer: The Meaning of Madness

CHAPTER SIX

The Philosopher: Bullet Proof

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Novelist: Gladsadness

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Evolutionary Biologist: He-Town

CHAPTER NINE

The Economist: A Pretty Good Utopia

WRAP-UP

So What?