CHAPTER FIVE

The Freudian Lawyer

The Meaning of Madness

The easiest way to get students to think about the mind-body problem is to bring up mental illness. Many find debates over consciousness, free will and the self too abstract, but they all care about depression, anxiety and substance abuse. These disorders force us to ask, in an especially urgent way, who we really are.

Modern psychiatry, I inform my classes, has embraced the physiological paradigm of mental illness. It stems from flawed genes or neurochemistry and is best treated with physiological remedies, such as antidepressants. This emphasis is good in some ways, because it reduces the stigma of insanity. It’s not demonic possession, or your parents’ fault, or a failure of character or willpower. It’s a disease, like diabetes. But this view can lead to despair if you think that biology is destiny. Also, medications are far from a panacea. That’s why psychological therapies persist, from cognitive-behavioral therapy to mindfulness meditation. So what is the evidence for various theories and therapies? And why do attitudes toward mental illness vary so widely across eras and cultures?

I encourage students to write about these questions—and, if they choose, to describe how mental illness has affected them or people they know. This personal approach, I say, can be a good way to hook readers emotionally and pull them into your story. When my students take advantage of this first-person option, their papers often surprise and dismay me. Here is a sampling from a recent class, with names changed. Tyler wrote about his brother’s depression, Karen about the suicide of a teenage friend, Trevor the heroin addiction of his girlfriend’s mother. Melanie admitted that she never felt much sympathy for people who were depressed until, out of the blue, “IT” struck her:

One minute I am a happy girl, I have had a perfectly good life so far, and I have never really pondered anything upsetting or had any major setbacks. The next minute IT happens… stress, anxiety, dietary changes, sleeping changes, moodiness, risky behavior, apathy, hopelessness. IT hit me like a bulldozer out of left field.

One drawback of this assignment is that papers are impossible to grade. If Jennifer reveals her fear that she has inherited her mother’s crippling depression, I’m not going to complain that her kicker lacks oomph. Students seem to find disclosing personal struggles cathartic. As Melanie wrote:

When I finally started talking about the problems I was having, it turned out that so many people around me were having or had had similar issues. Several of my close friends came out to me about their struggles with depression, and many of them are currently on treatment for depression.

Mental illness exacerbates the solipsism problem, our inability to know each other. We feel weird and ashamed, so we keep our illness secret, which can make it worse. But sharing our suffering can relieve our pain and help others, too. To dramatize this point, I tell my students the story of Elyn Saks.

Saks has impressive scholarly credentials. After graduating from Vanderbilt at the top of her class, she earned a master’s in philosophy from Oxford. At Yale Law School, from which she graduated in 1986, she edited the law journal. The University of Southern California Law School hired her in 1989, and she became Orrin B. Evans Distinguished Professor of Law, Psychology, and Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. In 2010 she got a doctorate in psychoanalysis, the theory/therapy invented by Freud.

Saks has written books on psychoanalysis, multiple-personality disorder and the rights of mentally impaired patients. Not until The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness was published in 2007 did Saks reveal why she has so much expertise and interest in insanity. She is a schizophrenic. Let me restate that, and this is an important distinction. She is a person who has struggled with schizophrenia. Only a few family members, friends, colleagues and therapists knew about her illness before the release of her memoir.

Center is packed with objective information. Saks notes that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM, which represents the consensus of the American Psychiatric Association, distinguishes between disorders of thought and disorders of mood. She writes:

Schizophrenia is an example of a disorder that affects thinking, and so it is referred to as a thought disorder. Bipolar disorder (what used to be called manic depression) is an example of a mood or “affective” disorder—a disorder that rests primarily in how one feels. The DSM places schizophrenia among the thought disorders characterized by psychosis. Psychosis is broadly defined as being out of touch with reality—what one of my Yale professors once referred to as “nuts.”

What makes Saks’s memoir extraordinary are her subjective descriptions. Take her recollection of a breakdown at Yale Law School. It began with her babbling incoherently to classmates in the library and twirling around in a professor’s office, arms “thrust out like bird wings.” She spewed “word salad,” streams of words loosely associated with each other, as though an internal punning function had gone haywire. “My name is Elyn. They used to call me ‘Elyn, Elyn, watermelon.’ At school, where I used to go. Where I am now and having trouble… There’s trouble. Right here in River City. Home of the New Haveners. Where there is no haven, new or old. I’m just looking for a haven.”[1]

She ended up in an emergency ward of Yale-New Haven Hospital, where attendants forcibly sedated her. Here is what that felt like:

Strapped down, unable to move, and doped up, I can feel myself slipping away…. On the other side of the door, looking at me through the window—who is that? Is that person real? I am like a bug, impaled on a pin, wriggling helplessly while someone contemplates tearing my head off. Someone watching me. Something watching me. It’s been waiting for this moment for so many years, taunting me, sending me previews of what will happen. Always before I’ve been able to fight back, to push until it recedes—not totally, but mostly, until it resembles nothing more than a malicious little speck off to the corner of my eye, camped near the edge of my peripheral vision… Nothing I can do. There will be raging fires, and hundreds, maybe thousands of people lying dead in the streets. And it will all—all of it—be my fault. [Emphasis in the original.]

Before the ascendance of the biological paradigm of mental illness, many psychiatrists assumed that schizophrenia resulted from childhood trauma, usually inflicted by parents. But Saks, who grew up in Miami, had an idyllic childhood. “I woke up almost every morning,” she recalls in her memoir, “to a sunny day, a wide clear sky, and the blue green waves of the Atlantic Ocean nearby.” Her parents weren’t perfect, no parents are, but they doted on Saks and her two brothers.

Elyn Saks (far left) and other members of her family in Miami circa 1965.

Schizophrenia “rolls in like a slow fog,” Saks writes, “becoming imperceptibly thicker as time goes on.” At seven or eight, she displayed “little quirks,” like repeatedly washing her hands, or imagining a bad person lurking outside her bedroom window. She had bouts of what she calls “disorganization,” in which “consciousness gradually loses its coherence,” and her self dissolves into a jumble. In college she had friends and a boyfriend, but sometimes she forgot to bathe, and she once compulsively swallowed a bottle of aspirin. When she and her boyfriend made love, the loss of self-control alarmed her. It felt like “disorganization.”

She had her first full-blown psychotic break in the late 1970s at Oxford, where she was pursuing a master’s in philosophy. Beings within her insisted she was evil and deserved to die. She burned herself with cigarettes and fantasized about dousing herself with gasoline and setting herself on fire. One day, she looked at herself in a mirror. “Holy shit… Who is that?” she recalls thinking in her memoir. “I was emaciated, and hunched over like someone three or four times my age. My face was gaunt. My eyes were vacant and full of terror. My hair was wild and filthy, my clothes wrinkled and stained. It was the visage of a crazy person.” She committed herself to a hospital and reluctantly took medications.

Saks has been hospitalized three times for periods totaling hundreds of days. Doctors called her prognosis “grave,” which meant that she would probably never be fully autonomous or have a sustained romantic relationship, and she would hold, at best, menial jobs. But she refused to succumb to her illness. Although she feared speaking in class and writing papers, professors kept giving her good grades. At Yale a professor called to tell her she’d written the best exam in the class. “Each time it happened,” Saks recalls, “in spite of the grades I’d earned in the past, this kind of comment came as a surprise.”

Saks with two philosophy professors and their wives at Vanderbilt University, 1972.

In 1998 Michael Laudor, celebrated for graduating from Yale Law School in spite of his schizophrenia, stabbed his fiancée to death. This incident prodded Saks into writing her memoir. She wanted to counteract the stigma surrounding schizophrenia, to assure people that “the large majority of schizophrenics never harm anyone.” She also wanted to give hope to others with mental illness, to let them know that a diagnosis “does not automatically sentence you to a bleak, painful life.” In an especially poignant passage of her memoir, Saks dwells on how schizophrenia differs from illnesses like cancer and heart disease.

Who was I, at my core? Was I primarily a schizophrenic? Did that illness define me? It’s been my observation that mentally ill people struggle with these questions even more than those with serious physical illnesses, because mental illness involves your mind and your core self… If, as our society seems to suggest, good health was partly mind over matter, what hope did someone with a broken mind have?

Good question. I wanted to ask Saks about her success, and whether it had anything to do with how she viewed her illness. Did she see schizophrenia as strictly physiological? Was it in any way a gift as well as a curse? Had her psychoses given her any insights into mind-body puzzles like free will and the nature of the self? What did her madness mean to her?

* * * * *

When I called Saks to ask for an interview, she responded with what I would learn was characteristic modesty. “I don’t know that I know much about the mind-body problem,” she said. She agreed to meet me after I assured her that she had just the kind of personal and professional expertise I was seeking.

As I walked, on a blindingly sunny summer day, onto the University of Southern California Campus, I wondered what Saks would be like in person. As the narrator of her memoir, she seemed warm and witty, but I was prepared for sharp edges, prickliness, guardedness. Saks’s psychoses seethed with violent imagery. In her memoir, she describes how thoughts “crashed into my mind like a fusillade of rocks someone (or something) was hurling at me—fierce, angry, jagged around the edges, and uncontrollable.”

My assumption was that mental illness makes you too self-absorbed, preoccupied with your distress, to be considerate of others. That’s how I was when I got depressed in the early 1980s. In Sylvia Plath’s quasi-fictional memoir The Bell Jar, she was cold, even cruel, to some of her desperately unhappy friends.

I knew I had found Saks’s office in the Gould School of Law when I came across a door covered with cartoons:

A shrink says to Humpty Dumpty, who lies on a couch, “Eventually I’d like to see you put yourself back together.”

A drowning man says to a dog, “Lassie, get help!” In the next panel, Lassie is lying on a couch talking to a therapist.

A caller to the “Psychiatric Hotline” listens to the options: “If you are OCD, please press 1 repeatedly. If you are co-dependent, please ask someone to press 2 for you. If you have multiple-personality disorder, please dial 3, 4, 5 or 6.”

I was jotting down the jokes when the door opened and a woman stood before me. She was tall, with noble facial features, high forehead, long, straight nose, firm, full-lipped mouth. She looked like Athena, except less prideful, and she wore not a toga but black pants and a black-and-white striped turtleneck. Her hair was thick, gray, untamed.

“Are you John?” She met my eyes with a level gaze. I apologized for being early. No problem, we could talk after she went to “the loo” (an aftereffect of her Oxford days). We spent an hour in the faculty lounge, down the hall from her office, and then walked to a nearby campus restaurant, where we sat outside.

I couldn’t help scrutinizing Saks for symptoms. She walked stiffly, arms at her sides. Her hand trembled slightly as she raised a cup of tea to her lips. Side effects of medication? As we talked in the faculty lounge, several colleagues got drinks or snacks from a counter. Each time Saks swiveled to see who it was and say Hi. Is that odd? I wondered. At the restaurant, she went to the “loo” again and took a while to return. She confessed that she had momentarily forgotten we were sitting outside. Tests showed that she had a “moderately bad memory.” She wasn’t sure if the cause was her illness, her medications, age or something else.

How oppressive to know that people are always watching you, interpreting you, judging you in the light of your illness. We all have quirks, but most are dismissed as amusing or annoying. Not so the peculiarities of someone diagnosed with schizophrenia, which psychiatrists describe as causing “bizarre” thoughts and behavior. Does any other medical diagnosis include such a judgmental criterion?

Saks was, for the most part, remarkably unremarkable. Her face and words were expressive, and she laughed easily and often. The biggest surprise was how humble and considerate she was, even sweet. “I feel bad that you would come all this way just to see me,” she said. She was glad when I said I had visited old friends in Los Angeles, abashed when I said I contacted them only after arranging to meet her. She pressed me for details on my book project and responded with utterances of encouragement, like “Wow” and “Amazing.”

At one point I recalled a line in her memoir, “I used to be God, but I got demoted.” Her quip, I said, reminded me of a psychedelic trip during which I became God and freaked out. Long after the trip, I said, I had scary flashbacks. As the words left my mouth, I felt mortified. I was a paintball player bragging to a veteran of the Battle of the Bulge. But Saks nodded sympathetically. She took mescaline in high school, she said, at a drive-in movie with friends. She remembers seeing a lot of colors. The experience didn’t really resemble her psychotic states, she said, but it “scared the shit” out of her. She was so upset that she told her parents about her trip, “which any reputable teenager would never do.” She laughed.

The intensity of her illness has declined, as it does for many people with schizophrenia. “It’s sort of silly to quantify it in this way,” she said, but when she was at Oxford, up to 80 percent of her thoughts were psychotic. That figure has declined to under five percent today. She hasn’t had the kind of breakdown that leaves her “crouched in the corner shaking” for more than a decade. She still has to manage her illness. “I don't have the flexibility that other people have,” she said. She tries to minimize travel and public speaking, which make her anxious. She reads student papers but no longer teaches in a classroom.

I confessed I had been nervous about meeting her, because I hadn’t known what to expect, but she was… I stopped before I said “normal,” but the unsaid word hovered between us. She smiled. If she was offended, she didn’t show it. When I asked if she had always been so “nice,” she laughed. She recalled a student evaluation that said, Professor Saks is a very nice person but a very mediocre teacher. She thought she had always been pretty nice, which explained why, even at her sickest, she had friends who could help her. Her illness has also made her more considerate. “Going through what I went through can make you more empathetic.”

She is acutely aware of how much her success has depended on luck. In her memoir she writes, “I’d feel terrible to learn that anyone had read this book and said to a family member or friend, ‘She did it, so can you.’” She had many advantages, including supportive friends, excellent medical care, meaningful employment and loving, affluent parents, who could afford to send her to college and graduate school. “Treatment, people and work are the three things that helped me,” she said.

Saks has dedicated herself to helping others less fortunate than she, of whom there are far too many. Decades ago, many state mental hospitals closed as a result of supposed improvements in anti-psychotic medications, and legal reforms made it harder to hospitalize patients against their will. This trend “could have been a good thing if it put other services in place,” Saks said. But many mentally ill people end up on the streets, homeless, or in prison because they lack adequate care.

Mental illness poses agonizing legal and ethical dilemmas, Saks said, for which there are no easy solutions. Take the case of “Billy Boggs,” a woman who lived on the streets of New York City in the late 1980s. New York City officials, responding to complaints that Boggs was harassing passers-by, hospitalized her against her will. The American Civil Liberties Union helped Boggs win her release, expanding the rights of the mentally ill to reject treatment.

When Saks asked law students how Billy Boggs should have been treated, they had “conflicted feelings.” Most said that, if they were judges, they would not commit Billy Boggs. “When I say, ‘What if Billy Boggs were your sister?’ many will say, ‘Well in that case I would take her to a hospital.’” When they imagined being Billy Boggs, many students replied, “I wouldn’t want to be forced.”

Saks leaned toward giving people as much autonomy as possible. In her 2002 book Refusing Care, she argues that people should be forcibly restrained and medicated only if they are endangering themselves or others.[2] Saks has also challenged the “myth” that people with the illness are prone to violence. “The reality is we account for two or three percent of violent crime,” she said. People with schizophrenia “are much more likely to be the victimized than victimizers.”

Reason can persist even in the floridly psychotic. As an example, Saks cites the case of Daniel Schreber, a German judge who became psychotic in 1884, when he was in his early 40s. In a 200-page tract published in 1903, when he was locked up in an asylum, Schreber explained that had become a woman to seduce God, who had been threatening him. He and God were getting along fine now, which was a “glorious triumph for the Order of the World.” Schreber concluded his mad memoir with what Saks called a “totally lucid” legal argument against the involuntary commitment of the insane. Schreber won a few years of freedom, but he died in an asylum in 1911.[3]

To counteract the stigma of mental illness, Saks and several colleagues are carrying out a study of “high-functioning” people with schizophrenia. They include physicians, lawyers, a teacher and the CEO of a nonprofit. Most have not publicly disclosed their illness, and “they tend to make less money than someone with a similar position.” But these cases show that people with the illness can live independently, hold good jobs and enjoy friendships and romantic relationships.

In a 2013 New York Times essay, “Successful and Schizophrenic,” Saks notes that the subjects of her study cope with their illness in diverse ways. They pray to God, challenge their delusions, drown out their inner voices with music, immerse themselves in work. When she feels herself “slipping,” Saks writes, she reaches out to doctors, friends and family, eats “comfort food,” like cereal, and cuts back on stimulation. Work is her “best defense,” because it “keeps me focused, it keeps the demons at bay. My mind, I have come to say, is both my worst enemy and my best friend.”

Saks never regretted going public about her illness. Yes, an administrative colleague at the law school pulled away from her after her memoir was published, and an alumnus of USC law school complained that it should not have hired her. But she has received “an outpouring of kindness and affection and gratitude.” No longer having to keep her illness secret has been an enormous relief.

And yet she still hesitates to disclose her disease to strangers. If someone sitting beside her on a plane asks about her life, she usually doesn’t mention her illness. When a patient-advocacy group asked her to wear a t-shirt that read, “Schizophrenia,” she declined. People with cancer “wear armbands and pins and t-shirts with pride and in solidarity and without shame,” she said. “That’s the way it should be with schizophrenia, but we’re not there yet. We’re just not there.”

We fear what we don’t understand, and schizophrenia remains profoundly mysterious. The consistent epidemiology of schizophrenia suggests that it is at least partially genetic. It afflicts roughly one percent of the global adult population, and onset usually occurs in the late teens and early twenties. If your parent or sibling has schizophrenia, your risk of getting the disease rises as high as 10 percent. If your identical twin is schizophrenic, the risk is almost 50 percent. On the other hand, a majority of people with schizophrenia have no first-order relatives with the disease.[4]

Researchers have linked schizophrenia to many non-genetic factors, including viruses, the self-replicating proteins called prions, emotionally cold “refrigerator mothers,” poor maternal nutrition, maternal smoking, birth complications and an assortment of childhood traumas. No one really knows, in other words, what causes schizophrenia.

When I first reported on schizophrenia in the late 1980s, scientists were confident that they would soon link it to genetic mutations and brain abnormalities, and that these findings would lead to improved treatments, even cures. These hopes were never fulfilled. Researchers disagree over whether schizophrenia is a disorder of the brain or the mind, a product of nature or nurture. Symptoms are often confused with those of bipolar disorder, severe depression and multiple-personality disorder.[5] Saks wasn’t given a definitive diagnosis of schizophrenia until she had been ill for years.

Some experts, including Saks, question whether schizophrenia is a single disease. Symptoms fall into two categories, positive and negative. The former include auditory hallucinations, jumbled thoughts and speech, bizarre delusions and behavior. The latter range from apathy to complete non-responsiveness, or catatonia. Saks lacks negative symptoms. “I am very different from someone who sits in front of a TV in a dayroom all day,” she said. Medications have helped her, but they are often ineffective at treating negative symptoms.

Saks suspects that schizophrenia is at least partially genetic. One other person in her extended family has been diagnosed. But she emphasized that she views schizophrenia as a biological disorder for a pragmatic reason, because it makes accepting pharmacological treatment easier. Early in her illness, she resisted medications. If she could get better without them, she reasoned, that would prove her diagnosis was “a terrible mistake.” Only after she suffered a breakdown in the mid-1990s did she stay on meds once and for all.

She is well aware of concerns that antipsychotic medications have debilitating side effects. Saks showed signs of the movement disorder called tardive dyskinesia on the anti-psychotic Navane, but the syndrome faded when she switched to newer drugs, Zyprexa and clozapine. “I would not even think about getting off meds at this point,” she said. “They really help me.” If she had to choose between gaining 10 or 20 pounds and being psychotic, she’d accept the weight gain. “A hundred pounds, and I might feel differently.”

We fear mental illness, but we fetishize it, too. Madness “is the channel by which we receive the greatest blessings,” Socrates says in Phaedrus. “Madness comes from God, whereas sober sense is merely human.” This view has persisted. The book and film A Beautiful Mind, about mathematician John Nash, who won a Nobel Prize in economics in 1994, suggest that Nash’s schizophrenia and genius were intertwined. Nash discerned patterns no one else could see. Although some of his perceptions were delusional, others led to major advances in game theory.[6]

During her psychoses, Saks often felt buffeted by divine or demonic forces. Some visions resembled the counter-factual thought experiments she encountered while pursuing a master’s in philosophy. Philosophy and psychosis “have a lot in common, more than philosophers would care to admit,” she said.[7] Philosophers “play with things that psychotic people live.” Descartes and others toyed with solipsism, the idea that nothing exists beyond your self. “No philosopher walks around thinking there is no external world,” Saks said, “but some psychotic people do.”

Saks has always resisted seeing her psychotic thoughts as revelations. Far from giving her deep insights into reality or the mind-body problem, they tend to be “sub-standard,” “troubled,” “confused.” She was once struck by Capgras syndrome, which convinces you that friends and loved ones have been replaced by identical imposters. Saks didn’t think she was glimpsing a deep truth about the illusory nature of the self. The syndrome terrified her and convinced her to stay on meds.

Nor does Saks see insanity as a kind of non-conformity, an appropriate response to an insane world. This view was popularized by counter-culture psychiatrists like R.D. Laing and Thomas Szasz and films like King of Hearts and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Szasz and Laing raised “interesting and difficult philosophical questions about mental illness,” Saks said. But she believed that “people who adapt to the crazy world are a lot happier and more successful.”

Saks has no affection for her illness. “I don’t really romanticize being psychotic,” she said. At the end of her memoir, she quotes Rilke explaining why he shunned psychoanalysis. “Don’t take my devils away,” he wrote, “because my angels might flee too.” Saks rejects that stance. If she could take a pill that cures her, banishing her devils, she would do so “in a heartbeat.” Most of the people she knows with schizophrenia feel the same way.

But Saks, again, does not insist that others share her perspective. “I take the view that it’s biochemical and responds to medication and therapy not because I have done the heavy philosophical lifting but for the pragmatic reason that it makes my life better. If it makes your life better to think it’s an alternative way of being, and a window into the mind of the cosmos, or whatever it is, good for you! Whatever works for you.”

* * * * *

Saks does not view schizophrenia as merely a biological disorder, treatable only with medications. Although she dismisses the cosmic, metaphysical import of her psychotic thoughts, she thinks they have personal psychological significance, which she has explored through psychoanalysis.

Saks’s affinity for the theory/therapy invented by Freud is a remarkable subplot of her remarkable story. She has tried other therapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, which focuses less on excavating the past than on changing negative thought patterns. “I know it has got a strong research base, but for me it was kind of silly and infantilizing.” She finds psychoanalysis “richer and deeper” than rival approaches.

Saks first underwent psychoanalysis after her breakdown in Oxford, where physicians recommended that she see an analyst four or five times a week. Freud, ironically, thought psychotic patients could not form the bond with the analyst needed for successful treatment. But Saks’s analyst, whom she calls “Mrs. Jones” in her memoir, practiced a type of psychoanalysis developed in the 1930s by Melanie Klein, who believed psychosis is treatable.

Klein, who thought Freud exaggerated children’s sexuality, focused on love rather than sex, but her view of childhood was hardly sentimental. According to Klein, love, because it makes us dependent on someone else, inevitably leads to fear, anger and other negative emotions. Even as babies, we seethe with desire and rage. In our first six months, we go through a “paranoid-schizoid” period, during which our emotions have no clear object, because we cannot distinguish between ourselves and others.

Later we pass through a “depressive” stage, in which the objects of our love, especially our mothers, also evoke fear, hate and envy. These feelings trigger guilt and self-loathing. We feel mixed emotions toward loved ones throughout our lives. Psychoanalysis, ideally, helps us overcome negative emotions by recognizing their causes.

The Kleinian analyst tries to remain “anonymous,” Saks explained, becoming a blank slate on which the patient projects her emotions. In her case, the technique worked almost too well. Saks loved and loathed Mrs. Jones, whom she called “an evil monster,” “the devil,” “a witch.” Saks once threatened to kidnap Jones and imprison her in her apartment. Nothing rattled the analyst. She treated her patient’s outbursts as opportunities for insight. Saks, in her memoir, calls Jones “the glue that held me together” at Oxford.

Saks grew up in a family in which expressing negative emotions was discouraged. “You were supposed to feel respect for your parents and never get angry.” As a result, she was “illiterate psychologically.” But Mrs. Jones encouraged her to express her strangest, darkest emotions. In her memoir, Saks recounts this exchange:

Me: I had a dream. I was making golf balls out of fetuses.

Mrs. Jones: You want to kill babies, you see, and then make a game out of it. You are jealous of the other babies. Jealous of the your brothers, jealous of my other patients. You want to kill them. And then you want to turn them into a little ball so you can smack them again. You want your mother and me to love only you.

Saks saw other analysts after leaving England. “I know that termination is part of the process,” she told me, but she is “a lifer.” She is also a trained analyst herself. In the mid-1990s she enrolled in a doctoral program run by a psychoanalytic institute in Los Angeles. As part of her training she treated patients under the supervision of another analyst. She stopped only after her memoir was published, because she had lost her anonymity.

Psychoanalysis works in several ways, Saks said. It “creates a safe place” where you can express your “dangerous and chaotic and scary thoughts” to a caring person, and it helps you cultivate an “observing ego.” Mrs. Jones got Saks to see her violent thoughts as a “defense against fear. And that made me understand, and made the fear go away.” Self-knowledge can be painful. “You learn some bad things about yourself, some unpleasant things, guilt-producing things,” Saks said. Psychoanalysis helped her understand that along with “the good, Pollyanna Elyn,” there is also “the Elyn who is envious and jealous.” But knowledge of yourself in “all your complexity” is ultimately empowering.

* * * * *

Saks calls psychoanalysis “the best window into the mind” and the “most interesting account of what it is to be human.” Jung and others produced interesting variants, but Freud is “the granddaddy” of psychoanalysis, Saks said. He was “an amazing writer” whose case studies “read like novels.”

And yet Freud may be the most maligned figure in the history of science. As soon as he started proposing his ideas in the late 19th century, critics pounced on him, with good reason. Freud never provided solid empirical evidence for the superego/ego/id triad, infantile sexuality, the Oedipal complex, penis envy, death instinct, transference, the repression theory of dreams and all the other conjectures that comprise the sprawling corpus of psychoanalysis.

Freud’s most adamant modern critic is Frederick Crews. Crews was a prominent practitioner of Freudian literary criticism before rebelling against his former idol. With the zeal of an apostate, Crews accused Freud of lies, greed, megalomania and cocaine-abuse in a series of sensational articles in The New York Review of Books in the 1990s. In 2017 Crews renewed his assault in Freud: The Making of an Illusion. The New York Times described it as “700-plus pages of Freud mangling experiments, shafting loved ones, friends, teachers, colleagues, patients and ultimately, God help us, swindling humanity at large.”

Here’s the question. If Freud was really such a fraud, why do many modern mind-scientists, like Christof Koch and Alison Gopnik, still cite him approvingly (albeit with qualifications)? Why do Elyn Saks and many other people still undergo psychoanalytic treatment? Why does Freud remain so influential that Frederick Crews must keep returning to “stab the corpse again,” as a reviewer put it? The answer is that old theories die when better ones replace them, and science still hasn’t produced a theory/therapy potent enough to render psychoanalysis obsolete.[8]

Comparisons of the many variants of psychoanalysis to cognitive-behavioral therapy and other psychotherapies show that all have roughly the same outcomes. Over the past half century, medications have become the dominant treatments for mental disorders, but they are much less effective than proponents claim. Medications help some people, especially in the short term, but over the long run, for large populations, they may do more harm than good. As prescriptions for psychiatric drugs have surged in the U.S., so have disability payments for severe mental illness.[9]

Just as the biological paradigm for understanding consciousness has collapsed over the past two decades, so has the biological paradigm of psychiatry, which emphasizes physiological rather than psychological causes and cures. Schizophrenia demonstrates this point. In the 2016 book Schizophrenia and Its Treatment: Where Is the Progress?, psychologist Matthew Kurtz notes that “outcomes for people with the disorder have remained highly recalcitrant to change over the past 100 years.”

These are negative reasons for Freud’s persistence. The positive reason is that Freud was an intrepid, imaginative, eloquent explorer of the mind-body problem. Unlike, say, most treatises on the physiological basis of mental illness, Freud’s work is dense with meaning. Literary theorist Harold Bloom has ranked Freud alongside such great modern writers as Proust, Joyce and Kafka and extols “his vision of civil war within the psyche.”

When critics harp on Freud’s failures as a scientist, they are committing a category error. Would we care if we learned that Shakespeare was a misogynistic bully and boozer who mangled history in his plays and stole ideas from other writers? Maybe we’d care a little, but we would probably keep reading Shakespeare, because he helps us make sense of the tragicomedy of our lives. So does Freud. Trying to make sense of the mind-body problem, he concocted stories with the depth and subtlety of great literature. And when it comes to understanding the mind and its disorders, at this point all we have are stories.

That is not to say that anything goes. In her 1991 book Interpreting Interpretation Saks examines different philosophical takes on psychoanalysis. One holds that interpretations of a patient’s symptoms are simply “stories,” and if a story makes a patient feel better, that is all that matters. Facts are irrelevant. Saks rejects this attitude, pointing out that false stories can have devastating consequences.

When she was writing Interpreting Interpretation, many therapists were encouraging patients to “recover” memories of sexual abuse by parents or other adults. Therapists said they didn’t care if the memories were false, as long as they made patients feel better. Saks calls this view irresponsible and potentially destructive. Truth matters, too. Her pragmatic philosophy could be summarized as follows: If you are ill, believe whatever works for you—whatever helps you overcome your illness and live a good, meaningful life—but try to avoid beliefs that are demonstrably false and harmful to you and others.

When I asked Saks if she believed in free will she responded, “Oh God, that’s a really tough one.” She leaned toward “soft determinism,” which says that all our acts are caused, but we nonetheless have free will as long as our acts are not compelled. She wasn’t comfortable with this stance, because she didn't see that much distinction between causation and compulsion.

I pitched my idea that free will must exist if we have more of it at some times than others. She has more free will now, for example, more capacity for self-control, for discerning and acting on choices, than when she was psychotic. She certainly has more than when she was medicated and locked up against her will. “That’s an interesting idea,” she said, nodding. “I think you should spin it out.”

I found Saks’s modest response ironic, because I see free will, or freedom, as her polestar, the central theme of her life and work. More than the rest of us, the mentally ill are constrained, not just by their biology but also by cultural and medical prejudices, by legal and economic conditions, by the whims of insurance companies and politicians. Saks wants to ease these constraints. She wants others afflicted with mental illness to be as free as possible to choose their own mind-body theories and therapies, their own stories. She wants to empower them to figure out who they really are and find happiness on their own terms, as she has.

* * * * *

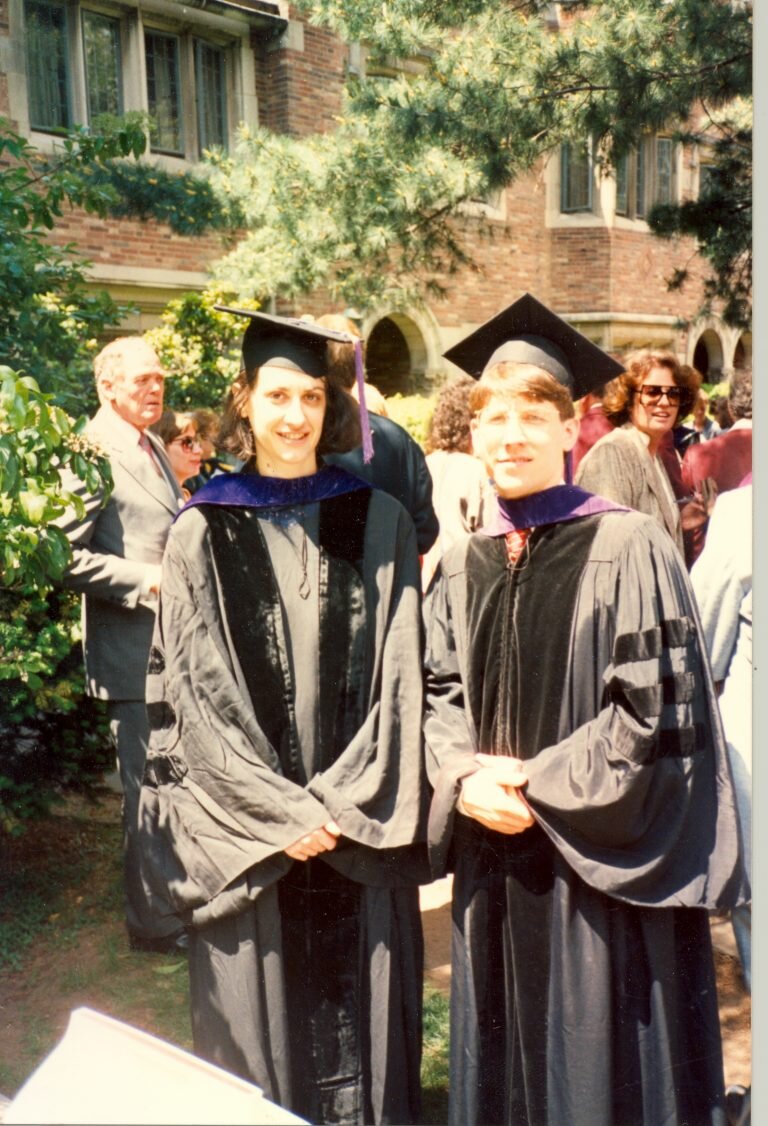

Saks and a classmate at their graduation from Yale Law School, 1986.

In 2014, singers performed an opera based on The Center Cannot Hold in Los Angeles. The opera, which a composer created with Saks’s collaboration, ends with Saks and her Yale classmates, in caps and gowns, celebrating graduation. Elyn exults that she has gotten a mentally ill client released from a hospital. Meanwhile her classmate Dan is in despair. His client, after Dan got him freed, burned down his home, killing his father, mother and brother. This is a real incident, which Saks describes in her memoir. “I’ve won my case, spit in my face,” Dan sings bitterly.

“That’s awful Dan,” Elyn sings to him. She agonizes over whether her fight for patient rights, inspired by her own forced treatment, is misguided. “How can I know?” she wails. She adds defiantly, “No! I won’t be tied down to a bed ever again!”

Another classmate, Steve, tells her he has fallen in love and is moving away. Elyn begs him not to leave her, and he assures her she will do fine without him. He urges her to keep fighting for patients’ rights. “I am so proud of you, Elyn,” he sings. “Your life has been the story of fighting for what you need and winning…. You have therapists, friends, professors, clients who believe in you. You will survive, and you can thrive.”

In addition to schizophrenia, Saks has survived three bouts of cancer and a stroke, and she has indeed thrived. In 2009, she won a MacArthur “Genius” Award, and she used the money to found the Saks Institute for Mental Health Law, Policy, and Ethics. Every year, the institute hosts a conference on a different mental-health issue, including mechanical restraints, medications, criminalization of mental illness and cinematic portrayals of madness.

In 2001 Saks married Will, a librarian at the USC law school. He accommodates her needs. He doesn’t mind that she works seven days a week, because he knows she finds the routine comforting. “We both love being together, but we love being apart as well,” Saks told me. “So I’ll come home, and we’ll sit in front of the TV and eat dinner together. And then I’ll go to my room and listen to music, and he’ll go to his room and work on the computer. It suits us well.”

Saks somehow combines fortitude—a ferocious determination to overcome obstacles—with intellectual humility. My friend Jim McClellan, the postmodern historian who insists that even our best scientific theories are “stories,” would appreciate her view of mental illness: Don’t ask whether psychopharmacology, behavioral genetics, Buddhism, Jungian dream analysis or other approaches to mental illness are true. Ask whether they work.

Some of us struggle more than others to find something that works, that gives us meaning and happiness, but we all struggle. My students remind me of that when they write about how mental illness has touched them. After we go over their papers, which can be harrowing, I show them a 2012 TED talk by Saks that has been viewed millions of times. Since meeting Saks, I find the video even more moving, because I know how much she hates public speaking. “The humanity we all share,” she concludes, “is more important than the mental illness we may not. What those of us who suffer with mental illness want is what everybody wants: in the words of Sigmund Freud, ‘to work and to love.’”

Freud, our gloomiest self-help guru, offered what was in some respects a dark vision of the human condition, in which forces beyond our comprehension torment and even destroy us. Psychoanalysis nonetheless rests on two upbeat assumptions: We can understand ourselves better if we work hard at it, and self-knowledge can ease our distress.

Freud once said the goal of psychoanalysis should be turning “neurotic misery into common unhappiness,” but Saks has done better than that. When I asked if she was happy, her face lit up. “Yeah! Yeah!” she replied, as if surprised at her own answer. Her current psychoanalyst “thinks of me as someone who’s unhappy, I guess because I bring my unhappiness there.” She laughed. “I think I’m happy and my analyst thinks I’m not.” Even when her illness was acute, she had “moments” of happiness, and now she has many more. “I think I have a really good life,” she said.

Someday science might produce gene therapies or brain implants that eradicate schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. We will then face a momentous choice, because such technologies could also conceivably cure us of common unhappiness and angst. We might become so content, even blissful, that we cease agonizing over who we are. The mind-body problem will no longer be a problem, because we will no longer be human. In that world, perhaps, Freud will finally be dead.

Listen to Saks talk about psychoanalysis, Los Angeles, July 2016.

Notes

[1] I was recently sitting beside a fountain in Washington Square Park, and the Grateful Dead lyric popped into my head. “There is a fountain/that was not made/by the hands of man.” The way my mind jumped from the real to the lyrical fountain reminded me of Saks’s compulsive punning, which in turn made me think of the shape-shifting verbiage of Finnegans Wake by James Joyce, whose daughter Sophia suffered from schizophrenia. I was jotting down these thoughts in my notebook when a young man walked up to me and offered to tell me a couple of jokes. If he made me laugh, I would give him a dollar. Deal, I said. Clean or dirty joke? he asked. Dirty, I said. What do you get when you finger-fuck a gypsy who’s having her period? You get your palm red for free. Gross, I said. He told me a clean joke. Where do sick ships go? To the dock. I laughed and gave him a dollar. I told him that just before he came up to me, I had been writing about the connection between punning and schizophrenia. The joker’s smile froze and he departed.

[2] Saks urges the use of advanced directives, in which people with a history of illness specify, when they are lucid, how they want to be treated when impaired. The directive can allow the patient to refuse most treatment, or it can call for hospitalization and medication even if the psychotic person refuses them. Saks calls this approach “self-paternalism.” A related strategy, “supported decision-making,” allows the mentally ill to decide with the help of families and mental-health professionals how they want to be treated. This method has worked with the developmentally disabled and demented, Saks said, leading to “higher treatment compliance and less hospitalization and all sorts of good downwind effects.”

[3] Freud, after reading Schreber’s Memoirs of My Nervous Illness, concluded that his delusions stemmed from fear of castration and repressed “homosexual libido.” Schreber couldn’t accept his desire for other males, such as his father and physician, so he transferred those desires to God. In a 1991 paper in Psychoanalysis and Contemporary Thought, Saks suggests, respectfully, that Freud’s interpretation was too narrow and sexualized. Schreber didn’t fear castration, Saks asserts, he feared losing his reason and identity, his “psychic integrity.” Schreber’s intense affair with God reflected the terrible loneliness that his illness had inflicted on him. Schreber feared a life without love, so he “desperately clings to the one relation that survives his illness,” his relation with God.

[4] For a critique of research on the genetics of schizophrenia, see “Schizophrenia and Genetics: A Closer Look at the Evidence.”

[5] Saks examines multiple-personality disorder, which many psychiatrists prefer to call dissociative-identity disorder, in her 1997 book Jekyll on Trial. People with the disorder have two or more distinct identities, or “alters,” that act autonomously. One alter has no control over and may not remember actions by another. Saks says the disorder was probably over-diagnosed decades ago as a result of its portrayal in the popular books and films The Three Faces of Eve and Sybil, and some psychiatrists remain skeptical of the diagnosis. But clinical studies and her own interviews with patients have convinced her that the disorder is real. Pointing out that we all have many selves, Saks asks, How different is someone with the disorder from the rest of us? Should we view the separate personalities of someone with the disorder as distinct people or as parts of a divided self? Our answers to these questions have legal implications. “How we think about responsibility depends on how we conceptualize ‘alters,’” Saks told me. If one alter commits a crime, is it fair for others to be punished?

[6] A 2011 study of 300,000 Swedes published in the British Journal of Psychiatry suggests that whereas people with schizophrenia are not especially creative, their healthy siblings are “overrepresented in creative professions.”

[7] I was reminded of Saks’s comment on the link between psychosis and philosophy while reading the paper “Absent Qualia and the Mind-Body Problem” by Michael Tye for a philosophy salon. Trying to refute the concept of “zombies,” human replicas that lack conscious experience, Tye proposes an experiment involving a conscious human and his unconscious doppelganger: “Imagine that a complex device has been constructed with dual heads-caps, each with probes protruding from its inner surface—probes that painlessly penetrate the skull when the head-cap is worn. These head-caps are connected to one another and other supporting machinery and computers in such a fiendishly clever way that when a switch is thrown, tiny robots enter the brains of the two people wearing the head-caps through the probes and make various internal changes with lightning speed before withdrawing back up the probes. The result of these changes is that there is a partial exchange of phenomenal states and non-phenomenal states between the two people, an exchange that continues after the head-caps are removed.” Italics added. Fiendishly clever indeed.

[8] I first spelled out this thesis in a 1996 Scientific American article, “Why Freud Isn’t Dead” and in a chapter with the same title in The Undiscovered Mind. I keep reiterating the thesis in blog posts, such as “Why Buddha Isn’t Dead,” “Why B.F. Skinner, Like Freud, Still Isn’t Dead” and “Why Freud Still Isn't Dead,” which mentions Elyn Saks’s affinity for Freud.

[9] The possibility that medications do more harm than good is explored in Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America, by journalist Robert Whitaker. I recommend his book, as well as a website he helped found, rxisk.org, which provides information on psychiatric drugs and other medications. See also my blog posts “Are Psychiatric Medications Making Us Sicker?”, “Psychiatrists Must Face Possibility That Medications Hurt More Than They Help” and “Return of Electro-Cures: Symptom of Psychiatry's Crisis?” For more columns on mental illness, see “Meta-Post: Horgan Posts on Antidepressants, Brain Implants, Psychedelics, Meditation and Other Therapies for Mental Illness.”

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

The Weirdness

CHAPTER ONE

The Neuroscientist: Beyond the Brain

CHAPTER TWO

The Cognitive Scientist: Strange Loops All the Way Down

CHAPTER THREE

The Child Psychologist: The Hedgehog in the Garden

CHAPTER FOUR

The Complexologist: Tragedy and Telepathy

CHAPTER FIVE

The Freudian Lawyer: The Meaning of Madness

CHAPTER SIX

The Philosopher: Bullet Proof

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Novelist: Gladsadness

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Evolutionary Biologist: He-Town

CHAPTER NINE

The Economist: A Pretty Good Utopia

WRAP-UP

So What?