CHAPTER EIGHT

The Evolutionary Biologist

He-Town

In June 2017 I traveled to Jamaica to interview Robert Trivers, who owns a house on six wooded acres on a hilltop near the island’s southern coast. Unwisely, perhaps, I talked my girlfriend, whom I’ll call Emily, into coming with me. She rolled her eyes when I called Trivers one of the greatest living scientists. You say that about everyone you interview, she said. What sold her on the trip was the prospect of relaxing on a Caribbean beach. We arrived at Trivers’s home early one evening and departed the next afternoon for a resort in Negril. During that time, my reactions to Trivers swung wildly between admiration, pity and fear. They still haven’t fully stabilized.

A couple of scenes to convey the man’s complexity. Giving me and Emily a tour of his land, Trivers pointed out a bulbous, spikey, bright green fruit dangling from a tree. It looked like the business end of a medieval mace. That tree is Annona muricata, called soursop by locals. Natural selection gave the fruit its distinctive shape for easy night-time detection by bats, which devour the fruit and excrete the seeds. Clever, eh? Trivers makes soursop tea by boiling the leaves in water and adding sugar and milk. The brew calms the nerves and helps you sleep.

We paused before another tree with bronze bark and dark, glossy leaves. A pimento, Trivers said, which produces allspice. The tree is unusual because it is dioecious, plants are either male or female. Most flowering plants are monoecious, each plant has male and female organs and hence can pollinate itself. The dioecious system is much less efficient, because male trees contribute so little to reproduction. Gazing fondly at the pimento, Trivers mused, “That these things survive in competition with other species is something of a mystery.”

Fruit of Annona muricata

Later, when I was alone with him in his living room, Trivers displayed knowledge of a different kind. If someone pulls a knife on you, he informed me, cross your arms in front of you, like this. Wait for your assailant to make his move, knock his knife hand aside with a forearm and punch him or go for his throat. He showed me a chokehold he learned from his pal Huey Newton. Gripping the back of my windpipe between his thumb and fingers, Trivers pinched until I winced. He apologized for hurting me, but did I understand how it would feel if he had squeezed hard? This hold can incapacitate any man, no matter how big and strong, and kill him if you keep squeezing. Massaging my throat, I indicated my appreciation for the lesson by nodding and grinning like a submissive ape.

Before I return to this tropical tale, some background. If you believe in science, as I do, you accept that natural selection created us. Whatever mind-body story you favor—integrated information theory, strange loops, Bayesian models, quantum consciousness, psychoanalysis—you must acknowledge that we are organisms designed for one purpose, making copies of ourselves. That, according to evolutionary biology, is who we really, truly are.

I nonetheless have a deep-rooted bias against biological explanations of human behavior. I fear they will discourage us from trying to create a better world by convincing us that the way things are is the way they must be. Historically oppressors, notably white, western, upper-class males, have invoked evolutionary theory to justify racism, sexism, imperialism, militarism and rapacious capitalism. Hierarchical social structures and inequality are inevitable. Those in power deserve it, because they are fitter.

Even Darwin, enlightened for his era, confused what is with what ought to be. In The Descent of Man he wrote that man displays “a higher eminence, in whatever he takes up, than woman can attain--whether requiring deep thought, reason or imagination.” This sort of thinking is not as overt as it once was, but it endures. It is invoked to explain why males have dominated science, mathematics and the arts.[1]

Many evolutionary hypotheses deserve to be derided as fanciful “just-so stories,” if not racism and sexism in scientific guise, but not the hypotheses of Trivers. In 1971 he took on one of biology’s deepest mysteries in “The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism.” Altruism consists of helping others at a cost to yourself. It is the essential moral act. Altruism toward those who share our genes is easy to explain in Darwinian terms, but why are we kind to non-kin, including strangers? Why jump in a pond to save someone else’s drowning kid? Why does my niece, a Harvard Law School graduate, work as a public defender in North Carolina, helping poor people accused of crimes, when she could make much more money as a corporate mercenary?

Trivers conjectures that natural selection instilled compassion and other moral emotions in us because our ancestors--over time and in the aggregate—received tit-for-tat benefits from acts of generosity. The emotions are instinctual, the end result of millennia of calculations by natural selection. But altruism could only propagate if natural selection instilled complementary tendencies in us, such as an exquisitely honed sense of fairness. If someone is kind to us, we feel grateful, and we want to reciprocate. If we are mean to someone who has treated us well, we feel guilt. We become outraged if we sense that someone is “cheating,” taking advantage of our kindness or that of others.

The emotions and instincts that nudge us to be kind, and to repay acts of kindness, might be absolutely sincere. But we are not just creatures of emotion and instinct. We also consciously, and rationally, help others with the expectation of reward. Worse, we deceive others about how generous and kind we are. We fake being good to get the benefits without the costs. Trivers backs up his thesis with elegant mathematical modeling, based on game theory, and examples of altruism-related behaviors in birds and fish. His reciprocal-altruism model, he points out, provides insight into “friendship, dislike, moralistic aggression, gratitude, sympathy, trust, suspicion, trustworthiness, aspects of guilt, and some forms of dishonesty and hypocrisy.” Trivers isn’t bragging, just stating a fact.

In two subsequent landmark papers, “Parental investment and sexual investment” (1972) and “Parent-offspring conflict” (1974), Trivers explains why hatred and cruelty abound even within families. Parents share no genes with each other and only half their genes with offspring. A female can only produce offspring every nine months. A male can in principle have countless offspring, but he cannot be sure a child is his. Given these genetic conflicts of interest, it is not surprising that parents sometimes become bitter enemies and even abandon offspring. These papers could serve as an appendix to What Maisie Knew, in which parents behave atrociously to each other and to their daughter, and to Alison Gopnik’s books on kids.

“The human altruistic system is a sensitive, unstable one,” Trivers writes. That could be the greatest understatement in the history of science. The ideas of Trivers were rapidly popularized by other biologists, notably Edward Wilson in Sociobiology and Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene (for which Trivers wrote the forward). A 1977 TIME Magazine cover story on sociobiology hailed Trivers as “the boldest in applying the gene-based view to humans.” I wasn’t jiving when I told Emily that Trivers is a big deal.

Psychologist Steven Pinker says Trivers has “provided a scientific explanation for the human condition: the intricately complicated and endlessly fascinating relationships that bind us to one another.” Pinker calls Trivers “one of the great thinkers in the history of Western thought” and an “under-appreciated genius.” Trivers is “under-appreciated” at least in part because he is a difficult man, a hot-tempered, bipolar anti-authoritarian with a taste for booze and weed. He has often, by his own admission, sabotaged his own career.

* * * * *

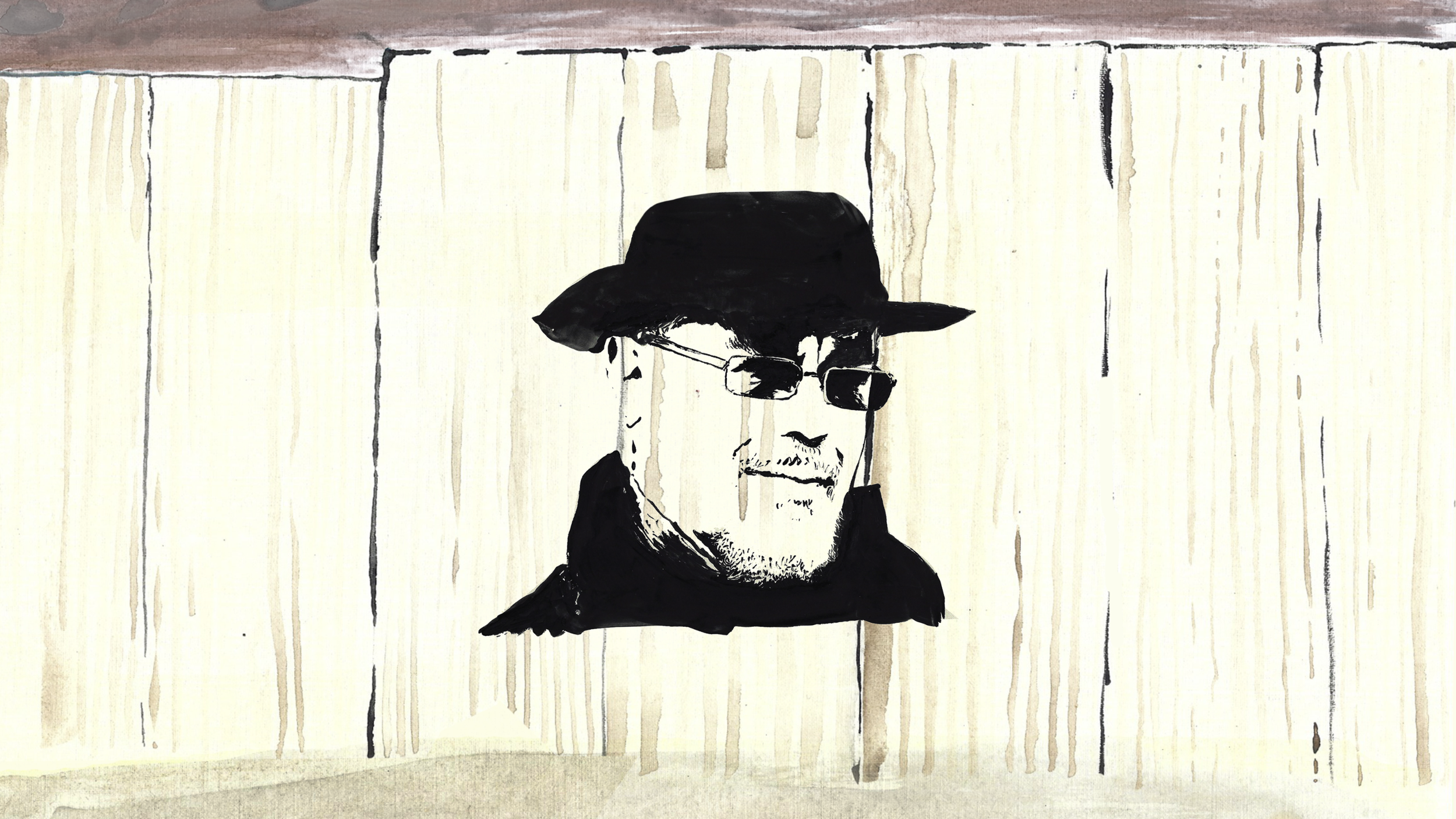

I first crossed tracks with Trivers in 1995, when I attended the annual conference of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society in Santa Barbara, California, a pep rally for evolutionary psychologists and social scientists. Prominent Darwinians were there, including Dawkins and Pinker. I was chitchatting outside the conference hall when someone pointed out a scruffily bearded guy in a knitted cap and tinted glasses smoking a joint with two other men. That’s Bob Trivers, my informant said. I approached Trivers, identified myself as a reporter for Scientific American and asked for an interview. He eyed me suspiciously and waved me away.

My report on the Evolution Society meeting was published in Scientific American in October 1995. I gave the article the admittedly provocative title “The New Social Darwinists.” Social Darwinism was a noxious 19th-century ideology inspired by evolutionary theory. Here is an excerpt from my introduction:

Watching [Darwinians at the conference] bonding, bickering, preening, flirting and engaging in mutual rhetorical grooming, one must concur with their basic premise. Yes, we are all animals, descendants of a vast lineage of survivors sprung from primordial pond scum. Our big, wrinkled brains were fashioned not in the last split second of civilization but during the hundreds of thousands of years preceding it… But just how much can Darwinian theory tell us about our modern, culture-steeped selves? Even enthusiasts admit that the field has much to prove before it can shake the old complaint that it traffics in untestable “just-so stories” or truisms.

And so on. I didn’t quote Trivers, but I mentioned his “bracingly cynical” theory of reciprocal altruism. I tried to be fair. I acknowledged that evolutionary theory offered intriguing ideas about our tastes in beauty and morality, and about behavioral differences between males and females. But I suggested that its hypotheses were short on evidence, and they often mirrored social stereotypes, especially about gender. After the article was published, Trivers sent me a letter. An excerpt:

I was disappointed in your shallow piece on evolutionary psychology… Even on trivial matters you are resolutely ignorant. My reciprocal altruism paper is “bracingly cynical.” Please! Do you know what the word cynical means and have you ever studied the work you so characterize? If our sense of justice evolved, as I surely believe it has, it must have done so by benefitting those possessing a sense of justice. That’s cynicism?! No, that’s logic. You are once again overwriting and underworking. Your work reveals a recurring problem serious scientists have on the subject of human behavior. Anybody with half a brain can mock thoughts on human behavior and by leaving out the evidence and the details of the logic make any evolutionary position taken look feeble or unsupported. Why satisfy yourself with such a trivial endeavor?

I convinced myself that Trivers’s complaints were unfair—criticizing science is my job—but the letter stung. I remembered it in 2011 when an editor at The New York Times Book Review got in touch with me about a book by Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life. The editor said the book criticized the U.S. and Israel so harshly that he and his Times colleagues weren’t sure whether to review it. He asked me to take a look at it. If I thought the book deserved a review, I could write it.

Sure, I said. I knew before I read Folly that I would review it. Reviewing books for The New York Times is fun and good for the career. The only question was whether I was going to give Trivers a good or bad review. Part of me wanted Folly to be bad, so I could punish Trivers for disparaging my Scientific American article back in 1995, but I found the book fascinating.

“We are thorough-going liars, even to ourselves,” Trivers declares in his preface. He argues that deceit is a “deep feature” of all organisms, an inevitable consequence of brutal genetic competition. Viruses and bacteria employ subterfuge to sneak past hosts' immune systems. Possums play possum, and cuckoos avoid the hassle of raising offspring by laying their eggs in other birds’ nests. As organisms’ strategies for deceit have grown in sophistication, so have strategies for deceit-detection. This arms race has been a major driver of evolution.[2]

Our big brains and communication skills make us especially good dissemblers. Even before we can speak, we cry alligator tears to manipulate care-givers. As adults, we seize on facts that bolster our preconceptions and overlook contradictory data. Fooling others yields obvious benefits, but why fool ourselves? The more we believe our own lies, Trivers asserts, the more effectively we can lie to others. Our lies and illusions can have devastating consequences, from bad marriages to stock-market collapses, world wars and genocide.

As the Times editor warned me, Trivers is especially scathing toward the U.S. and Israel, which he accuses of repeatedly covering up atrocities with lies. He is hard on himself, too. He acknowledges deceiving girlfriends, family members, colleagues and himself. After being in a store, he sometimes finds items in his pockets that he has unconsciously shoplifted. He recalls walking down a street with an attractive young woman, feeling cocky, when he spotted an ugly old man walking beside them. To his shock he realized he was seeing his reflection in a store window.

I gave Folly a positive review. It ends:

Trivers is not an elegant stylist like Dawkins, Wilson or Pinker. His technical explanations can be murky, his political rants cartoonishly crude. But Trivers's blunt, unpolished manner--which I assume is not feigned—makes me trust him more than some slicker writers… Only in one passage does Trivers strike me as insincere, when he notes how prone academics are to self-importance; one survey found that 94 percent consider themselves to be above average in their fields. “I plead guilty,” Trivers adds. That, surely, is false modesty. I hope his new book gives Trivers the attention he so richly deserves.

I described Trivers’s political discussions as “rants” not because I disagreed with them but because I knew they disturbed the Times editors. That was cowardly on my part. After the review appeared, I considered inviting Trivers to my school to talk about Folly. I had heard rumors of misbehavior, so I checked up on him. A friend who saw him lecture in Germany said he was great, on top of his game. When I reached Trivers by phone, he said my review annoyed him, initially, but his editor convinced him he was being too thin-skinned. So sure, he’d come to my school for a modest honorarium.

In September 2012, Trivers gave a terrific talk to a packed auditorium. He got a big laugh describing experiments that revealed penises of homophobes swell in response to gay porn more than penises of non-homophobic straight men. Another hit: a video of a toddler who stopped or started bawling depending on whether his mother was in his line of sight. So young, so manipulative! He’ll go far in life.

I enjoyed my day with Trivers. I liked his growly hipster patter, the way he called me “brother.” He was so cool he made me feel cool. He listened carefully to what I said, and if he wasn’t sure what I meant, or if he thought I wasn’t sure, he demanded clarification. He had no tolerance for bullshit. I admire this trait, even when the bullshit in question is mine.

After Trivers gave his talk, we met a dozen students in my science-writing seminar. To jumpstart the conversation, I brought up the old complaint that evolutionary hypotheses are unconfirmable “just-so stories.” Trivers asked for an example. As a matter of principle, I refuse to be intimidated by scientists, but Trivers’s narrow-eyed gaze spooked me. I, a mere science writer, was bitching about Darwinian theory to one of the greatest Darwinians since Darwin. It was like complaining, “Well, Nils, quantum mechanics is a fine theory, but come on, we both know it’s overrated.” Who did I think I was?

I mumbled something about the Darwinian assumption that women are innately less promiscuous than men. Nurture, I said, could explain female coyness as well as nature. Girls learn at an early age that sex can get them in trouble. They are criticized for promiscuity far more than boys, and they run the risk of pregnancy. As I spoke, I was acutely aware of my students eyeing me. Like a pack of feral dogs watching their leader challenged by a bigger rival, they surely sensed my fear, the moisture on my brow, the tremor in my voice.

Trivers, as I recall, responded that even in societies with liberal sexual mores and accessible birth control, females are on average less promiscuous than males. The same is true of most mammalian species, suggesting that female coyness has a biological basis. His tone was mild, and he didn’t press the point. He didn't want to embarrass me in front of my pack. I felt grateful and humiliated.

When I got the idea for this book, I naturally thought of Trivers. In his 2015 memoir Wild Life, he describes his upbringing as the child of a diplomat, his first psychotic breakdown, his passion for nature and science, his love-hate relationship with Jamaica. After visiting the island in the 1970s to study birds and lizards, he bought land there. He also married and brought to the U.S. (in sequence) two Jamaican women, with whom he had four daughters and two sons. Trivers has fulfilled his biological function.

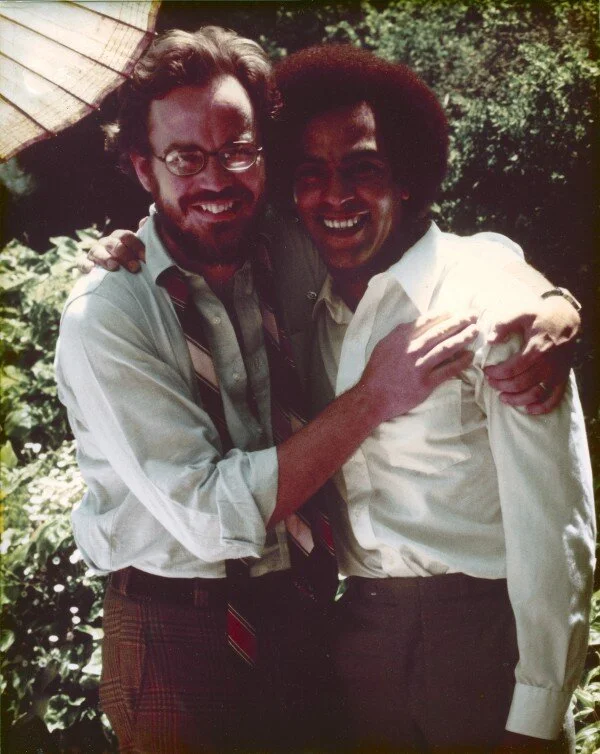

What sets Wild Life apart from most scientists' memoirs is the violence. Trivers recounts incidents in which he was robbed at gunpoint and knifepoint and fought off would-be assailants with his fists or a knife. Then there is his friendship with Huey Newton, who co-founded the Black Panthers. They met in 1978 when Trivers was teaching at the University of California at Santa Cruz and Newton was in prison. Studying for a doctorate in social science, Newton took a reading course on self-deception with Trivers. They remained close until Newton’s death in 1989. Trivers calls Newton a “warm, brilliant man” but acknowledges his “dark side.” Newton “brutally beat and murdered people of various ethnicities, sometimes for no crime at all.”

Trivers and Huey Newton at the christening of Trivers’s twin daughters, 1979. Newton became one girl’s godfather.

At the end of his memoir Trivers regrets his “absence of self-reflection.” I took this admission as an invitation. I would get him to reflect more deeply than he had in his memoir on his mental illness and affinity for violence. By the time I called him, he was living full-time in Jamaica. He was no longer affiliated with Rutgers, with which he had a tempestuous relationship, or any other university. He suggested we meet during one of his trips to the U.S. to give a talk or see his family. Jamaica is dangerous, he emphasized, with one of the highest murder rates in the world. Cab drivers were known to rob tourists.

I said I was willing to take the risk, and so was my girlfriend, who was coming with me. Okay, Trivers said. He would have a Jamaican friend drive us from the airport to his home, where no one would fuck with us. He has a firearm, and he has been trained in knife-fighting by a German cop who trained other cops. Listening to him, a joke popped into my head: Who protects us from our protector?

* * * * *

Trivers’s house was a one-story structure with three bedrooms and two bathrooms ringed by a yard of red dirt, on which several lean mutts lounged. Trivers was thinner than when he visited my school, more grizzled, stiffer in his movements. His speech was slower and more growly. He was unshaven, his white hair cropped short. He greeted me and Emily with seemingly genuine enthusiasm and gave us a tour of his home. I had expected, and led Emily to expect, a certain level of comfort, if not luxury. That expectation, I’ll just say, was not fulfilled. As we walked through the house, Emily nonetheless uttered noises of appreciation.

We paused before a wall covered with photos of women and children. Emily murmured approvingly as Trivers identified his wives, daughters and a son, and a sister who had died of cancer. Pinned to another wall were newspaper photos of a muscular female athlete. Emily laughed when Trivers said that he and Roy, a Jamaican man who helps him tend his land, like strong black women.

After I asked about coffee for the next morning, Trivers took us into the kitchen and pointed out a jar of instant coffee and can of condensed milk. When Emily inquired about a can opener, Trivers grabbed a big knife and made a stabbing motion. This is how we open cans here, he said with a rakish grin. Emily smiled brightly at him, then winked at me with an eye facing away from Trivers.

He led us outside onto a small porch. Night had fallen. The jungle seethed with the music of insects, birds, frogs and humans at a nightclub down the hill. Trivers told Emily that having a female visitor was a real treat. He and his pal Roy call this place “He-Town,” because women so rarely visit. I hope you won’t feel inhibited here, he said to her. It was too dark for me to see if Emily was winking at me.

We settled in the living room. Emily and I sat on a rusty metal love seat, Trivers at a table with a laptop and printer. He showed us two stories he had clipped from Jamaican newspapers: a captioned photo of a preternaturally curvaceous beauty-contest winner and a report on the murder of a 71-year-old man. These stories, Trivers said, capture Jamaica, land of beautiful women and bad men. Jamaica would be paradise if not for Jamaicans. He doesn’t say that, Jamaicans say that.

He abhorred the country’s vicious homophobia. He was organizing a group to defend gay men threatened by other Jamaicans. He wasn’t sure whether he and his fellow defenders should arm themselves with guns, knives or broken bottles. Nothing is scarier than a man wielding a broken bottle, he assured us.

He asked me to remind him of my book’s theme. After listening to my pitch, he said he didn’t see how the mind-body problem could be solved any time soon, given how little we know about the brain. “We are still weak on the biology.” Neuroscientists often overstate their knowledge. Trivers was fascinated by research on lie-detection, but he doubted reports that MRI scans can detect lies with 80-percent accuracy. Lie-detection researchers are probably hyping their results—lying!--to keep funds flowing from the CIA and other agencies interested in lie-detection.

He and Huey Newton, who shared his fascination with deception, speculated that liars often give themselves away by taking too long to answer a question--or, conversely, by reacting too quickly. Once, visiting Newton in prison, Trivers asked if he was going to smoke crack as soon as he got out. No! his friend replied, whipping his head back and forth. Then Newton smiled and added, Too fast, eh? Three months later Newton was shot to death outside a crack house in Oakland.

Trivers, who has always identified himself as an evolutionary biologist, knocked sociobiology and evolutionary psychology, fields that his work helped spawn. “Sociobiology is pure bullshit,” he said. Edward Wilson, often called “the father of sociobiology,” is only the father of the term. “Calling it a special name and acting as though it’s an independent discipline, you cut it off from its roots, its trunk!” As for evolutionary psychology, Trivers doubted a core proposition, that our minds and bodies have not evolved much since we were hunter-gatherers. In fact, Trivers said, plagues and other selection pressures can alter genes quite rapidly.

Abruptly switching topics, as he often did, Trivers revealed that he had gotten bad news that morning. A fellowship he had hoped to get in Denmark had fallen through. He was in the market for a job, any job, at any university, no matter how humble. Surely, I said, with all your admirers, you will get a job soon. “I’ve got a few detractors, too,” he said. If 10 people gather to honor him, at least one or two are thinking, “That motherfucker shouldn't get nothin’.” He laughed grimly.

He wanted not just a job but an intellectual “community.” “I get lonely here for intellectual, you know, companionship, such as we’re having here.” He had been looking forward to hanging out with me and Emily. When we were late coming from the airport us, he feared we had decided to go straight to our resort. Emily said, We were looking forward to meeting you, too, Bob!

Hey, Trivers said to me, maybe you can get me a gig at your school! Great idea, I said, except the school just got its biggest gift ever, $20 million, from a creationist alumnus, so it might be tough getting a Darwinian like you hired. I imparted this information with a big, phony grin (although the story about the gift was true). No problem, Trivers said, grinning back at me, he’ll teach a class on creationism and slip in a little evolutionary theory. After we chuckled over that, I suggested that we hit the sack and talk again in the morning.

* * * * *

I woke from fever dreams. Pale, pre-dawn light was falling through the windows. I heard noises. Trivers was up. Emily was awake too. She had slept even more poorly than I had because of the heat, bugs and barking of dogs. She was going to try to get more sleep. I got dressed, grabbed my notebook and recorder and found Trivers in the kitchen. He asked how we slept, and I said great. We settled in the living room. I had a mug of coffee, Trivers a mug of soursop tea.

As he did throughout the morning, Trivers scanned his computer for news of atrocities. Examples: A cop trying to shoot a pit bull ended up killing a child. Trivers was aghast. You can’t shoot a dog when it’s running around! He mimed the proper method for killing a bad dog. Wait for it to fasten its teeth on your leg and put a bullet through its skull. That seems sensible, I agreed.

He read aloud another story about a Dallas officer who shot at a moving car and killed a 21-year-old woman. “These police murders gall me so much,” Trivers said. In his youth, the murder of black civil-rights activists incensed him. When an all-white jury failed to convict Byron Beckwith, the white supremacist who killed Medgar Evers, Trivers thought “black people should take a page from Jewish history and send in an assassination squad.” That’s why he was thrilled to meet Newton, who shot a cop in self-defense. Trivers, who briefly belonged to the Panthers, said there “is still a little bit of Black Panther in me.”

Newton was legendary for his skill with firearms. He could supposedly kill someone in an instant. “Poof! Right through the head,” Trivers said, miming a quick-draw. Newton once offered to teach Trivers how to shoot, but he “stupidly” declined. He bought a gun after men armed with knives broke into his home and attacked him here in Jamaica in 2008. They had probably read newspaper reports about him receiving the Crafoord Prize, a scientific honor worth $500,000. He fought the assailants off with a knife of his own. “I figured next time robbers come, they are gonna come with bang-bang, because a cutting tool doesn't work with me.” He regularly practices at a shooting range. “A gun is only good as the man holding it.”

Trivers in Jamaica.

When I raised the issue of mental illness, Trivers cautioned that he did not follow “the literature on being nuts,” but he suspected his bipolar disorder has a genetic component. His father, the diplomat, who had a degree in philosophy, “was borderline crazy but just on this side. I was borderline crazy on the other side.”[3] He didn’t give much credence to the old idea that genius and madness are linked. Like Elyn Saks, he saw his illness as “destructive,” not creative. “I’ve not been romantic about it at all,” he said. “You don’t learn anything when you go crazy.” His manias, which usually culminated in hospitalization, lasted for a month or two and were followed by a longer period of depression and recovery.

When he first broke down in 1964 after a bout of increasing mania and sleeplessness, he didn’t know who he was. He was hospitalized for two and a half months. Thorazine “knocked the psychosis” out of him, and a milder drug, stelazine, kept him from relapsing. In the past, after emerging from a breakdown, Trivers would go off meds, but since an episode in 2000 he has remained on Depakote and clonazepam.

Trivers has had plenty of psychotherapy, too. Its chief benefit, he said, is that “you can tell a therapist things you can’t tell anybody else. Anybody. So let’s say I did get drunk and have a homosexual experience. Am I going to tell you, my closest male friend? No. I’m embarrassed of it, ashamed of it. So there were things I did in my life, out in California, in the bad old cocaine days, idiot days, I would share with my psychiatrist.” Trivers sees a therapist in New Jersey now and then. The therapist “mostly acts as a guard against my abuse of alcohol and marijuana. He’s always more concerned about alcohol, and he’s right.” But marijuana has harmed him too, he said, by reducing his scientific productivity.

Trivers credited Freud, the father of psychotherapy, with drawing attention to self-deception, repression, projection and denial. There is “no doubt we repress certain things, deny certain things, project certain things. So Freud had insights. However.” Freud wedded these ideas to a theory of early development—the oral, anal and Oedipal stages--that he “invented out of whole cloth, probably snorting too much cocaine.”

Freud got the idea for the Oedipal complex from female patients who claimed that men had molested them when they were girls. Freud believed the women initially, then decided they were fantasizing about sex with father surrogates. “He blamed the victim,” Trivers growled, disgusted. “So now it was women wanted these relations” because of their latent desire for their fathers.

The Oedipal hypothesis is preposterous, Trivers said. Sex between closely related organisms often leads to offspring with deleterious mutations. Evolution has therefore designed humans and other animals, including birds, to avoid copulation between parents and offspring, and especially between fathers and daughters. “In organism after organism, birds and mammals, there are well-developed mechanisms to keep you and your father apart.” That is not to say incest never happens.

Trivers knocked some modern psychological claims, too--for example, that optimism, which can be a kind of self-deception, promotes a stronger immune response and other health benefits. Trivers suspected that the researchers got the causality backward. Being healthy, with an immune system “purring along at peak efficiency,” will naturally make you feel better about life. “If you're healthy, you’ll be more optimistic!”

Trivers wrote an optimism researcher to propose his alternative interpretation. “I dummied up as if I’m naïve. ‘I really enjoyed your study of such and such, interesting correlation, but tell me, you interpreted this way, couldn't it also be interpreted so and so?’ She wrote back, listen to her: ‘We have been studying this for 21 years.’ I forget how she worded the rest of it, but it was like: ‘We’ve been making this mistake for 21 years, we ain’t about to change.’” Trivers guffawed. Talk about self-deception!

He liked research linking intelligence to deception. In a study of human four-year-olds, a researcher brings a box into a room, tells the child in the room not to look inside, leaves the room and watches the child through a one-way window. Most children look in the box. Most also lie about looking, and the smarter they are, the more likely they are to lie. “120 IQ or above, you lie 100 percent of the time,” Trivers said gleefully.

Trivers wasn’t aware of good research on intelligence and self-deception. Many intellectuals, he said, probably think they are less susceptible to self-deception than non-intellectuals. They reason, “‘I’m smarter, I’ve got better insight, I can see through it better.’ All right. My answer is, ‘Yeah you're smarter, so you’re quicker at rationalizing.’” Trivers can detect and analyze his own self-deception “post-facto,” after the fact, but not “pre-facto.” He often regrets retaliating against those who have slighted him and vows not to do it again. But the next time someone pisses him off, he persuades himself that retaliation is righteous.

He recalled a 1977 spat with Paul Samuelson, a Nobel-winning economist at Harvard. (With disdain, Trivers informed me that the Nobel Memorial Prize for Economics is administered by a bank, not a scientific society.) The Harvard economics department asked Trivers to give a talk, to which Samuelson would respond. Samuelson assured Trivers his response would be “positive.”

Then TIME Magazine quoted Trivers saying: “Sooner or later, political science, law, economics, psychology, psychiatry, and anthropology will all be branches of sociobiology.” This quote apparently offended Samuelson, who attacked Trivers after he gave his talk. “I started to get up at one point and interrupt him and say, ‘Listen motherfucker.’” A colleague restrained Trivers. During this period, the Harvard biology department delayed his tenure application, and Trivers, furious, accepted a position at Santa Cruz. “I had warned them, ‘Give me tenure or I’m leaving.’ And unfortunately I’m as good as my word.”

That was my opening, now or never. I found it “odd,” I said, that in his memoir he didn't reflect more on the “tough guy stuff.” His tendency to lose his temper, to get in fights, verbal and even physical. He could have been severely injured or killed in the fights.

“You got that right, brother,” Trivers said. He mused a moment. “Part of it was self defense,” he said. He learned to box in prep school to protect himself against bullies. His fighting has “a strong moral component,” he explained. If you are a “rabbit” and you are right, he will back down. But if he is right, even if you are much bigger and stronger, he will “probably go for you.”

But you didn’t just defend yourself, you sought out danger, I persisted. You befriended Huey Newton, an extremely violent man. What explains this fascination with violence? “Fascination I think is too strong a word,” Trivers said cautiously. And Newton’s violence was an “appropriate response to unpunished violence against black people” by police and others. Come on, I said, in your memoir you admit that some of Newton’s violence was unjustified. Surely you must have reflected on this tendency of yours.

Trivers took a big breath. “Damn. It’s a good question, man. You’re asking some good questions. And I don't have good answers. Which is, you know...” His voice trailed off. At some point during this interrogation, Trivers started moving restlessly around the room, picking up and setting down objects. Then, as if to rebut me, he confidently recounted an incident that took place in 1985 in Amsterdam. His marriage was crumbling, and he was in a foul mood. Unable to find an open brothel in the city’s red light district, he became belligerent, loudly insulting the Dutch. An “ugly” man emerged from the shadows and told Trivers that he would find him a woman. Trivers suspected the “ugly Hollander” meant to rob him or worse, but he followed him anyway, continuing to spew out insults.

When they were on the edge of a canal with no other people in sight, the Hollander, sure enough, pulled a knife. Trivers punched him, knocking him over. He planned to kill him with the chokehold that Newton had taught him, but the Hollander bolted. Trivers wrote up the incident for his memoir, but his editor hated it. “She went bonkers over the fact I was intending to kill someone. And then she said really stupid stuff, like, ‘You could have just walked away!’” Trivers mentioned the dispute to friends, and they agreed that “if someone puts your life on line, you have every right to put their life on the line.”

But his editor was right, I said. Trivers provoked the confrontation with the Hollander and kept following him even though he suspected the man intended to rob him or worse. He was spoiling for a fight. This is just another example of his attraction to violence. “I agree with you, I agree with you,” Trivers muttered. Maybe he should address this issue in the next edition of his memoir, he mused. He sat at his desk, grabbed a pen and paper and scribbled. “’Why… not… more… conscious… re… personal… violence.” He stared at the note. “Jesus Christ, I’m scared to even answer, brother.”

Trivers announced that he wanted to give me a tour of his land. I followed him outside. His property, which from the house looked like a mass of undifferentiated jungle, was laced with paths and dotted with structures. We stopped by a one-room building that Trivers erected in 1975, which now serves as a guest room, and a water tank he built a few years later. Trivers pointed out trees he had planted over the years. Pimento, almond, soursop, walnut, mango, wild cherry, June plum, aki, cotton, dwarf coconut. He was especially proud of a line of graceful willows planted to shield his home from hurricanes. During Hurricane Ivan in 2004, his was one of the few local homes that kept its roof.

In 1994 he bought what was supposed to be a half-acre from a neighbor for $5,000. Friends told him he might have been cheated, so Trivers carefully paced off the land. It wasn’t half an acre, it was three quarters. He gave his neighbor an extra $1,000. “His face was beaming,” Trivers recalled. “That don't happen in Jamaica, brother, I can tell you that.” Trivers beamed too remembering his good deed.

Toward the end of the tour, his pride yielded to melancholy. “It’s a fantastic piece of land, but so what? In the end, you know?” He doesn’t think his children will want to keep the land after he’s gone. It requires too much tending. They certainly don’t want to live in Jamaica. Pushing through the tall grass ahead of me he muttered, “It’s getting me depressed talking to you. Seriously.”

Back in the house, Trivers said when he retreated to Jamaica in 2016 he started having a recurrent dream. He is wandering around a strange city, lost. He can’t remember how to get back to his hotel, or even the hotel’s name. In some dreams, he calls 911 to ask for help, and he can’t remember his name. “So you know where I’m going, I’m going off to a mental hospital.” The dream “went on night after night after night for six fucking months.” Trivers thought it was a reaction to the final severance of his ties with Rutgers. Since then, for the first time in his life, he has had no base in the U.S. No home. Jamaica is a tropical paradise for birds and lizards, not for him. He will always be an outsider here.

* * * * *

It was late morning, hot and humid. I was beginning to feel like a dick, a sadist poking a wounded old wolf with a stick. I told Trivers I had all the material I needed. Emily and I would like to leave now, and not at two o’clock, as we had originally planned. Could Trivers call the driver and ask him to take us to Negril? The heat is oppressing Emily, I said. She didn’t sleep well last night, and she wants to go to our hotel, which has air conditioning. Trivers looked at me sharply, and I remembered that earlier I had falsely assured him that we slept well.

Trivers called the driver and left a message saying his guests wanted to leave as soon as possible. I asked about our options if the driver didn’t respond. Could someone else drive us? No, Trivers said, he couldn’t find someone trustworthy on such short notice.

Datura

Emily, who had been reading in our bedroom, entered the living room. She gave Trivers a present, a ceramic pipe decorated with leaves of Datura, a hallucinogenic plant native to Jamaica. “Thank you very much, God bless you, I will try it this evening,” Trivers said. He seemed distracted.

To lighten the mood, I said I had only a couple more “easy” questions, on free will and God. Trivers ignored me. Staring at his laptop he muttered, “He’s a hustler. He’s a cheap hustler, like Ariely.” Dan Ariely is a psychologist who, Trivers had told me earlier, lured him into giving a talk at MIT by telling him how much he admired his work and then, in public, “demolished” him. Was Trivers joking? Was he really upset with me?

Abruptly he left the room. A minute later Emily whispered, He has a gun. What do you mean? I asked. She had just seen Trivers walking past a doorway with a pistol in his hand. I was still processing this information when Trivers re-entered the room. He had changed his clothing. He was dressed in a clean white shirt, tie and dark blazer. I didn’t see a gun. As un-ironically as possible I asked, Why the fancy clothes, Bob?

He had an errand to run, Trivers said curtly. He would be back soon. He left the house. Emily and I were sitting on the front porch considering our options when Trivers returned. A neighbor had died, he explained, and he had gone to his house to offer condolences to the family. Also, he had finally heard back from the driver, who would be here soon.

We waited on the front porch for the driver to arrive. Trivers stood in front of me, sipping from a dark brown bottle of rum cream, jacket slightly askew. Now I saw the gun clipped to his belt. Bob, I asked, why the gun? Trivers replied that he always wore the gun when he left the house. No point having a licensed firearm on this island if you don’t carry it with you. I nodded.

Trivers, armed, seemed to stand taller and straighter, but it might have been my imagination. To my surprise, he recalled my previous question about free will. He said Huey Newton, shortly after they met, asked if he believed in free will. “I said, ‘Well, Huey, I don’t know exactly what people mean by free will, but we certainly evolved the capacity to look at our behavior afterward and adjust it appropriately.’ He embraces me and says, ‘We don't disagree on nothin’.’”

Trivers was intrigued by experimental evidence that our brains reach decisions a second or more before our conscious minds do. “So to that degree conscious free will is an illusion, as far as we understand it.” In the split second after your brain makes a decision, your conscious mind can “nix the damn behavior.” Otherwise, our conscious control over our actions seems limited.

I replied that I was a hard-core believer in free will, even though I recognized that we have a limited ability to control our actions. Emily chimed in, saying that in some cases we are “limited by our chemistry.”

Trivers looked at her, stone-faced. “Everything is chemistry,” he drawled. “So when you say that, you're not saying much.”

Coming to my lady’s defense, I said differences in neurochemistry, and genes, must explain why some people are so susceptible to alcoholism, drug addiction and depression. Fearing these examples might offend Trivers, I added that I had been severely depressed once, and it felt more chemical than psychological, I couldn’t reason my way out of it.

Friends can act as the voice of reason, Trivers responded, for example, by talking you out of retaliating against someone who has hurt your feelings. Your friend “did not suffer what you suffered, he does not give a flying shit about your pain. You know what I mean? So he can make a decision independent of fact that you just suffered a little bit of pain, and say, ‘Forget about your fucking pain! It’s in the past!’”

But your friend does give a shit about your pain, I said, he wants to spare you future pain, that’s why he’s telling you not to retaliate. Yes, Trivers said irritably, that was his point.

During this exchange, the driver pulled into the yard. Trivers watched Emily and me load our bags into the car. I shook his hand, Emily hugged him. “I’m sorry to see you go,” he said, and to my dismay he seemed to mean it. As the driver eased down the driveway, I turned in time to get a final glimpse of Trivers staring glumly at the jungle.

* * * * *

I spent the next week lolling with Emily on a sweltering white beach and in a frigid hotel room, worrying about how to describe our stay in He-Town. My job is to tell a story that is accurate, informative, fair, entertaining. “Fair” worries me most. Can I serve readers’ interests, and thereby mine, without betraying Trivers?

Trivers was a warm, gracious host. Before we arrived he bought fish for us and had sheets and towels laundered. He took us on a tour of his land and his town, which had a tourist attraction called Lovers Leap. He entertained us with scientific fun facts and tales from his life on the island and elsewhere. He answered my questions, even those that upset him. He bared his heart.

I still have doubts about Darwinian science. Theorists ascribe much of what we do to instinct, but it is often hard to know where instinct ends and reason begins. We can be calculating in choosing and achieving our goals, even the goal of reproduction. And we acquire many of our values and inclinations from culture rather than biology. This is the point I tried to make to Trivers and my science-writing class. Females’ sexual choosiness, relative to males, could be a learned, rational behavior rather than an instinct. The same is surely true of many manifestations of altruism. We are brainwashed to be nice from an early age, and we learn that niceness, and even pseudo-niceness, is rewarded.

Trivers has also clearly projected his belligerent psyche, the “tough guy stuff,” onto all of humanity. Whether because of nature or nurture, he sees even the most intimate relationships—between husbands and wives, parents and children, friends—as struggles. For this tempestuous man, at war with himself and with the world, life is a battleground, a contest for respect, status, reproductive opportunities.

But the more I contemplate the work of Trivers, the more profound it seems. It helps me understand why my reason and emotions, and selfishness and kindness, are so entangled. It gives me a little insight into the swirling, contradictory feelings I have when I interact with others, whether my girlfriend, children, friends, colleagues, students--or subjects of my journalism.

So my tale of He-Town is not meant to belittle Trivers and his ideas. Quite the contrary. It is meant, if anything, to pay homage to his view of human nature. Our meeting was, on its face, a straight-forward, tit-for-tat arrangement. I wanted material for my book. He wanted, I assume, a sympathetic portrayal that would burnish his reputation.

But once we met in He-Town, with a female looking on, cross-currents of emotion buffeted us. Between the two of us we felt sympathy, affection, delight, amusement, trepidation, mistrust, guilt, shame, loneliness, anger, melancholy. The more I reflect on my interactions with Trivers at He-Town, the more I realize they were just a high-pressure version of all my social interactions.

Trivers is right, life is a battleground, a war of all against all, even when the combat isn’t physical. Before we came to Jamaica, I told Emily I wanted to read something good, a juicy classic. I was thinking of trying Portrait of Lady. Had she read it? Was it any good? After expressing obligatory shock that I, a supposedly educated man, had never read Henry James’s greatest novel, Emily said, Yes, read it, it’s fantastic.

Reading Portrait in Jamaica, I was amused, at first, by the vast chasm between He-Town, where Trivers dwells, and the hyper-civilized realm inhabited by Isabel, James’s heroine, in which repressed ladies and gentlemen drift through European mansions and museums swapping witticisms. Call it She-Town. He-Town and She-Town seemed like planets inhabited by different species.

By the time I finished the book I realized how wrong my first impression was. Although Portrait lacks overt sexuality or physical violence, its ladies and gentlemen, including noble, brilliant Isabel, are whipsawed by desire, and they cruelly deceive and hurt each other. She-Town ain’t so civilized either. The novel also exposes, with terrible irony, the limits of free will. Isabel’s yearning for freedom ends up entrapping her in a miserable destiny.

Trivers has explained, as well as anyone, why it is so hard for us to be happy, to be good, to be honest. We are at war with ourselves as well as others, and our self-deception makes peace elusive. Our shared evolutionary heritage landed us in this tragic condition, which no one, no matter how privileged, intelligent and decent, can escape. But Trivers, whom I once implied was a cynic, isn’t. He doesn’t succumb to fatalism, despair or cheap irony. He believes passionately in truth, justice, honesty, loyalty, courage.

Darwinian theories of human behavior, historically, have been associated with right-wing, authoritarian ideologies, notably Nazism. Trivers, the greatest modern Darwinian, is an anti-authoritarian firebrand, a social-justice warrior. If he knows he is right and you are wrong, he’ll come after you, no matter how big and tough you are. He loathes bullies in any form, whether a loudmouth hitting on women in a bar, a white cop harassing young black men or a superpower bombing third-world countries into submission.

Trivers values honor, that most old-fashioned and masculine of virtues, above all, and that is his tragic flaw. He is so exquisitely sensitive to slights, injustices, betrayals that he lashes out even at admirers and allies. Trivers expressed regret over his “absence of reflection” in his memoir and during my visit. “If you add up all the mistakes I’ve made in my life,” he said, “four of my lives have been lost already.” He wishes he had been less impulsive and more calculating in how he lived his life.

Here is the paradox of Trivers. His immense intelligence has given him deep insights into the limits of intelligence, into why it is so hard for us to reason our way to happiness and moral decency. He keeps crashing against those limits, because he is a man of such strong passion. And what’s wrong with that? At the beginning of his memoir, Trivers says he was never content with merely studying life. He wanted to live it, and he has, with hot-blooded intensity. His mistakes no doubt cost him opportunities, especially for further scientific achievement, but he still accomplished more than the vast majority of scientists. And his life has been a wild ride, filled with near-death adventures, romance and derring-do. What more can a man want?

Not to lay too great a metaphorical burden on him, but Trivers embodies the contradictions of modern humanity. So enlightened, so benighted! No matter how much we learn about ourselves, we will always be missing something, on which our lives might depend. Given what Trivers has shown us about the depths of our folly, our deadly capacity for self-deception, can we create a truly just, free world? Can we save ourselves? Will my students and children be okay?[4]

I’ll wrap up with a couple of anecdotes in which Trivers revealed his paternal side. Once, while he was driving his four-year-old daughter Alelia home from school, she asked, Daddy, what is the last number? There is no last number, Trivers explained, because whatever number she thinks of, he can just add a one to it. “And then she said, ‘Like the sky?’ And it nearly blew me out of my seat.” Trivers’s grizzled face glowed as he recalled the incident. His little girl had intuited infinity.

He mentioned his offspring again while standing with Emily and me on the brink of Lovers Leap, a cliff that rises 1,700 feet above the sea. According to lore, the lovers were young slaves. The plantation owner, who wanted the beautiful slave girl for himself, planned to sell the boy, and in despair they hurled themselves off the cliff. After telling us this tale of love and injustice, Trivers pointed out Great Bay, where he used to swim with his kids when they were small. He would stand in the deeper water beyond them, looking shoreward, so he could rescue them if a current caught them. A question popped into my head. Who rescues the rescuer?

View from Lover’s Leap, Jamaica.

Listen to Trivers talk about mathematics and other topics in Jamaica, June 24, 2017.

Listen to Trivers and me talk on Meaningoflife.tv after this book was published.

Notes

[1] In 2017, after a Google engineer argued that women are unsuited for technology jobs, I wrote about the intersection of science and sexism in “Darwin Was Sexist, and So Are Many Scientists” and a follow-up post, “Do Women Want to be Oppressed?”

[2] I happened to be reading Crime and Punishment while working on this chapter, and I came upon a passage in which Raskolnikov’s pal Razumikhin celebrates lying in a way that struck me as Trivers-esque. “I like it when people lie,” Razumikhin says. “Lying is man’s only privilege over all the other organisms. When you lie, you get to the truth! Lying is what makes me a man. Not one truth has ever been reached without first lying 14 times or so, and that’s honorable in its own way. Well, but we can’t even lie with our own minds! Lie to me, but in your own way, and I’ll kiss you for it.”

[3] As this 2014 review indicates, some evidence suggest that bipolar disease is at least partially inherited, but attempts to link the disorder to specific genes have been inconclusive. After this book's publication, Trivers's oldest living sister, Ruth Ann Trivers Mekitarian, wrote me to object to her brother's description of their father as “borderline crazy.” Their father “had not a shred of crazy in him,” she said. She also informed me that her brother, an authority on intra-family conflict, had six siblings in all, two of whom have died.

[4] I would like to think I approach total honesty in my journals, where I record my private thoughts. But the more I think about it, the more I realize that my journal entries are not accurate representations of my private thoughts, the thoughts I have when no one is watching. Because someone is always watching, and that someone is me, or the part of me, the meta-me, that yearns for recognition and royalties, or, less crassly, for epiphanies, for self-validation, for phony moments of pseudo-understanding. William James touches on this truth when he compares thoughts to snowflakes. As soon as you catch a snowflake in your hand to examine it, it melts. The weird, awful implication is that our real thoughts, and real selves, are inaccessible to us. We are always posturing, deceiving ourselves and hence others. This happens not just when I’m writing but throughout the day. As I think my thoughts I’m also assessing, selecting, revising for possible expression. At least that’s my aspiration. Sometimes I’m too dull-witted to go meta, to posture, to deceive myself. I’m honest by default, because I don’t have the energy to deceive myself and others. Even these thoughts that I’m recording now, that total honesty is impossible, are phony. I’m acting, putting on a show. It’s phoniness all the way down.

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

The Weirdness

CHAPTER ONE

The Neuroscientist: Beyond the Brain

CHAPTER TWO

The Cognitive Scientist: Strange Loops All the Way Down

CHAPTER THREE

The Child Psychologist: The Hedgehog in the Garden

CHAPTER FOUR

The Complexologist: Tragedy and Telepathy

CHAPTER FIVE

The Freudian Lawyer: The Meaning of Madness

CHAPTER SIX

The Philosopher: Bullet Proof

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Novelist: Gladsadness

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Evolutionary Biologist: He-Town

CHAPTER NINE

The Economist: A Pretty Good Utopia

WRAP-UP

So What?