Oliver Sacks Fudged Facts. Does That Bother Me?

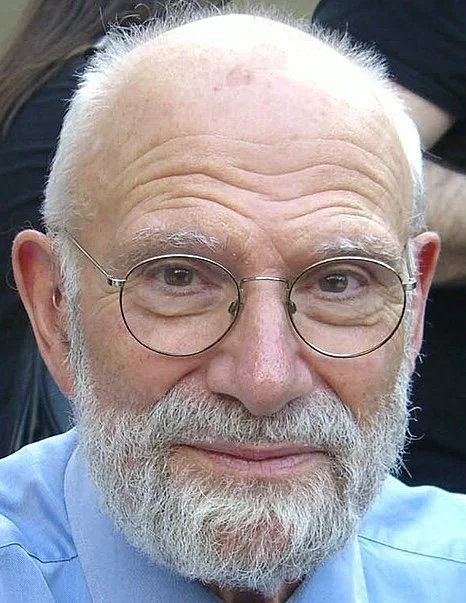

Oliver Sacks in 2009, from Wikipedia. He once told me that he was “content to multiply case histories and leave the theorizing to others.”

HOBOKEN, DECEMBER 22, 2025. Oliver Sacks made up details of his stories about patients with brain disorders, Rachel Aviv reports in the December 15 New Yorker. Does this revelation diminish my admiration for the neurologist/author?

Before I answer this question, a quick history of my interactions with Sacks, who died in 2015 at the age of 82. I first encountered his work forty years ago when I read The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. This collection of stories about patients disabled by strokes, tumors, autism, etc. entranced me. Who was this fellow Sacks, this wonder-struck explorer of the psyche’s farthest reaches?

I met him in 1997 when he showed up at a debate over The End the Science between me and John Maddox, editor-in-chief of Nature, in Manhattan. Peeking out from behind spectacles and beard, Sacks seemed less intrepid explorer than shy woodland creature.

I asked if I could interview him for a book on science’s attempts to explain the mind. Sacks tentatively agreed, then wrote me a letter saying he’d changed his mind. He was hurt by my description of him in The End of Science as a practitioner of “ironic” science, whose work was more “literary” than scientific. I had also savagely criticized a mind-theorist Sacks admired, Gerald Edelman.

Sacks nonetheless granted me a brief telephone interview, during which he explained his method, or anti-method. He tried to adhere to Wittgenstein’s dictum that books offer “examples” rather than generalizations. “People keep saying, ‘Sacks, where’s your general theory?’” he elaborated. “But I’m rather content to multiply case histories and leave the theorizing to others.”

After quoting these remarks in my 1999 book The Undiscovered Mind, I warned that while detailed descriptions of individual patients “often make compelling reading, they can obfuscate and subvert the truth.” I noted that Freud presented case studies, which “diverged sharply from the truth,” as evidence for psychoanalysis.

Case studies, I added, helped other scientists promote their own dubious theories of and therapies for the mind. (An especially egregious example is the 1993 bestseller Listening to Prozac, in which psychiatrist Peter Kramer claimed the antidepressant made his patients “better than well.”)

In 2008 I persuaded Sacks to talk to me about his book Musicophilia before an audience at my school, Stevens Institute of Technology. Sacks seemed terrified at first, but he quickly calmed down and charmed the standing-room-only audience.

After the event I wrote Sacks to ask if he had stage fright, which has long afflicted and fascinated me. Sacks wrote back that he did indeed suffer from stage fright. He said “this sort of tension, unpleasant though it is, is (for me at least) a prerequisite of performing well.” (Sacks’ letter to me is printed in Oliver Sacks: Letters, published last year.)

When Sacks visited Stevens, we hung out in my office a while. Noticing my many books on psychedelics, Sacks asked if I had taken these substances. When I said I had, this shy, reserved physician revealed, to my astonishment, that he had experimented with psychedelics and other drugs.

Sacks’ 2015 autobiography On the Move details his extensive use of illicit drugs. Sacks also recounts his struggles with homosexuality, which he suppressed for most of his adult life. Clearly, Sacks’s personal torment had given him empathy for and insight into even the most dysfunctional patients.

Back to the recent New Yorker article about Sacks. Rachel Aviv presents evidence that Sacks invented details about “Leonard,” a key figure in Awakenings. That 1973 book describes patients who “awakened” from a near-catatonic condition, caused by encephalitis, when treated by an experimental drug.

Sacks depicts Leonard as having been bookish and asocial in his youth, which he apparently wasn’t, and quotes him citing a Rilke poem about a caged panther, which he almost certainly didn’t. Aviv identifies other inventions in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.

Aviv, who has pored through Sacks’ voluminous private journals, proposes that Sacks projected his own anxieties, desires and insights onto Leonard and other patients. Her conjecture seems plausible, especially since Sacks admits as much. In his journals Sacks agonizes over his “fabrications” and calls his stories “a sort of autobiography.”

“Oliver Sacks, you broke my heart,” science journalist Maria Konnikova says in response to Aviv’s article. [Other science writers agree, see Postscript.] But Aviv, far from condemning Sacks in The New Yorker, treats him gently, with sympathy. She suggests that Sacks’ writings served as a kind of self-therapy, which complemented the psychoanalysis he underwent for decades. Aviv asserts, moreover, that Sacks stuck to the facts in An Anthropologist on Mars (1995) and later works.

Here is another reason to forgive Sacks for his early inventions: In marked contrast to Freud, Sacks never presented his case studies as evidence for a pet theory. Quite the contrary. Sacks was an anti-theorist, who abhorred the reduction of patients to pathologies or data points. Each patient, he insisted, should be seen as an individual, a marvelous, once-in-eternity individual.

Here is how Sacks put it in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat: “To restore the human subject at the center–the suffering, afflicted, fighting human subject–we must deepen a case history to a narrative or tale; only then do we have a ‘who’ as well as a ‘what,’ a real person, a patient, in relation to disease–in relation to the physical.”

In Anthropologist on Mars Sacks commented: “The realities of patients, the ways in which they and their brains construct their own worlds, cannot be comprehended wholly from observation of behavior, from the outside. In addition to the objective approach of the scientist, the naturalist, we must employ an intersubjective approach, too.”

The central mystery of science and philosophy, the mystery toward which all other mysteries converge, is the mind-body problem, which I’ve defined as the question of what we are, can be and should be. Sacks’ anti-reductionist, literary approach to the mind-body problem has struck me, over the years, as increasingly profound, and apt.

Each of us, Sacks reminds us, is unique and constantly changing in ways that resist scientific analysis and generalization; our idiosyncrasies and mutability, far from being extraneous, are essential to our humanity. This insight, this anti-theory, has philosophical, ethical, political and spiritual as well as scientific implications.

Sacks’ work inspired my 2018 book Mind-Body Problems, which argues that each of us struggles with our own mind-body problems, for which there can be no single, universal solution. I defend this thesis by telling the stories of nine mind-body explorers tormented by schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, a brain tumor, sexual confusion, loss of religious faith, alcoholism and grief at the death of a child.

Yeah, I’m skeptical of case histories, but I resort to them, too.

Now back to the question: Have Rachel Aviv’s revelations lessened my admiration of Sacks? Not at all. Sacks remains one of my favorite mind-body explorers, along with William James, Henry James, Virginia Woolf and James Joyce. And Douglas Hofstadter. Oh hell, I’ll include the old fabricator Freud, too.

If anything, Aviv’s investigation of Sacks deepens my appreciation of this wonderfully strange and gifted tale-teller. I feel even luckier to have crossed his path.

POSTSCRIPT: Science writers I admire have responded to this column on Facebook. Below are their comments, and my response.

George Johnson: A very nice essay, John. I don't feel quite so forgiving. The power of his stories comes from the assumption that what we are reading is true. And that is how Sacks presented them, as fact not fiction. If you’re returning to the hat book, see what you think now of “The Twins.” A well told story, yes, but basically science fiction. I wrote about this several years ago: https://talaya.net/twins.pdf. I’m looking forward to Laura J. Snyder’s biography of Sacks, which will apparently delve deeper into the issues raised in The New Yorker article.

Michael Brooks: John, I’m afraid I’m with George. It’s dishonest to present what are received as medical case histories as fact when they are knowingly embellished, however artfully. It undermines all of us science writers: people could reasonably assume we are all at it. It also makes it impossible for us to (honestly) live up to publishers’ elevated expectations of what good science storytelling should look like. I for one feel very sad to learn that Sacks allowed himself to tell lies in order to burnish his reputation as a teller of extraordinary stories (and presumably to inflate his advance/royalty payments).

John Horgan responds: Yes, but but but... I just re-read "The Twins." It is such an extraordinary riff on the nature of cognition, understanding, whatever you want to call it. The story is filled with anecdotes, from others' writings, about how some mathematicians, rather than calculating their way to insight, simply "see" the answer, as if they have an intuitive affinity for numerical patterns and harmonies underpinning existence. How does it happen? Yes, the key part of "The Twins," which gives it mystical oomph, is the scene in which the twins are "swapping twenty-figure primes." Sacks made that up, I've concluded after reading Rachel Aviv. That's bad. But I still love "The Twins," because it makes me feel so powerfully, viscerally, the strangeness of the mind, of mathematics, of existence.

Faye Flam (responding on Facebook to George Johnson): This is the most insightful thing written on this whole Sacks controversy - and you saw it years ago. The prime number claim was a case of selective gullibility - any honest investigator or writer with an ounce of critical thinking ability would have tested the twins with big numbers that were not primes. And I agree that making up facts or data is a cardinal sin because it undermines the whole purpose of science or non-fiction science writing.

Further Reading:

You can read my collection of case histories, Mind-Body Problems, for free on this site or in paperback and e-book editions. Yeah, everything comes down to pushing product.