My Personal Paradigm

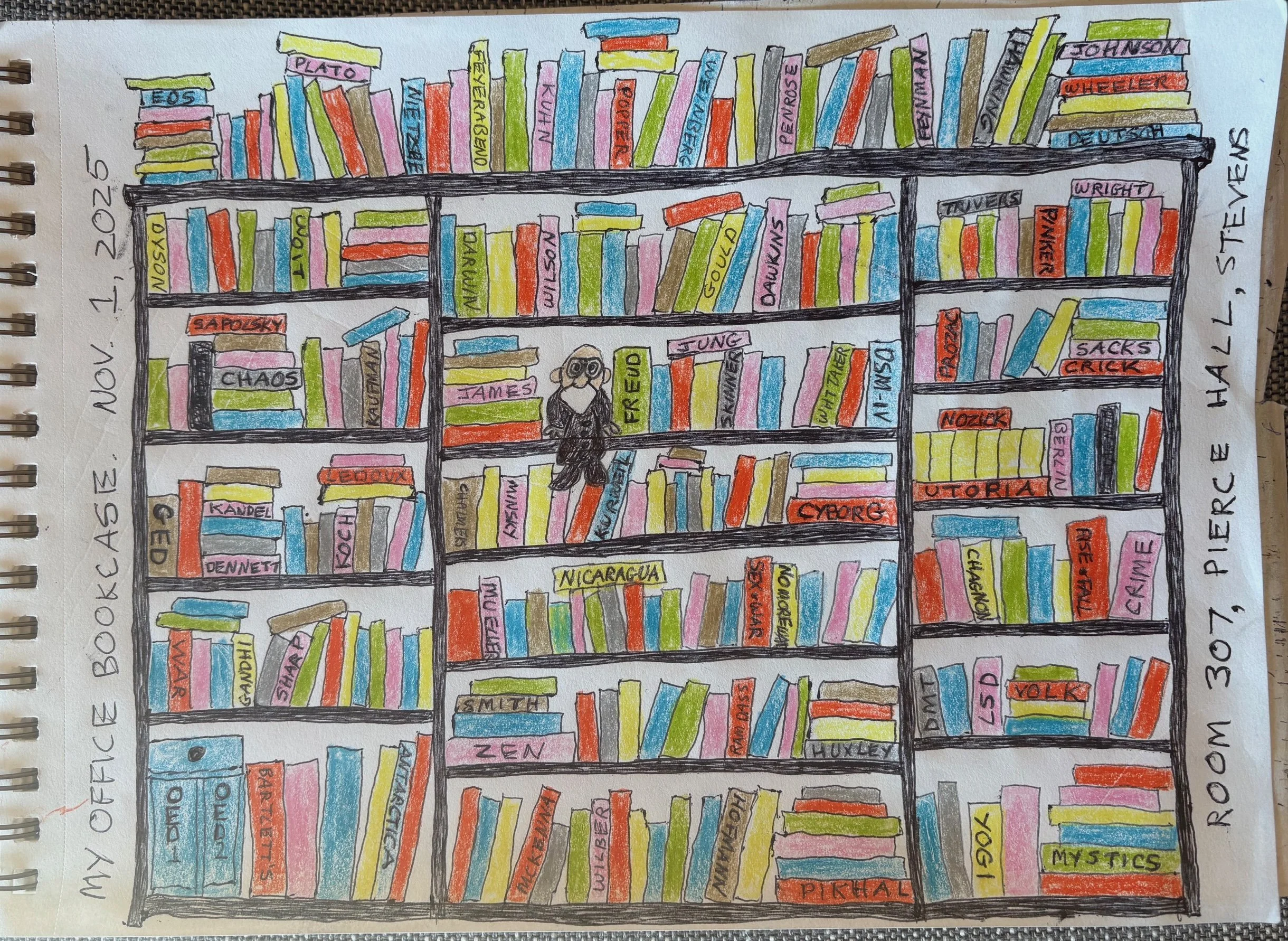

This bookcase, which holds the books that helped me write my books, represents a tiny piece of my personal paradigm.

HOBOKEN, NOVEMBER 3, 2025. I wake at 2 AM and feel the rough draft of this column uploading, against my will, in my brain. I lie in the dark, shuffling phrases, sentences. An opening paragraph comes to me, I fear I’ll forget it. I shuffle into the living room, flip my laptop open, click on “PERSONAL PARADIGM.”

I’m dimly aware, as the “PERSONAL PARADIGM” file pops open, of the many other folders and files scattered across my desktop. These contain articles and books, syllabi, student papers, recommendation letters, tax returns, medical records, toasts, eulogies, a divorce decree, last will and testament and so on.

I’m writing this column because—it occurs to me—the info on my laptop is just a minuscule digital synecdoche of the sprawling database in my head. This consists of explicit and implicit memories, doubts and convictions, fetishes and phobias, values and taboos, you name it.

You have your own version of this database. It’s what makes you you and only you. You might call it your “psyche” or “self,” but in this column I’m calling it “my personal paradigm.”

Yes, I’m borrowing paradigm from Kuhn. By paradigm, Kuhn means the often-unspoken assumptions, habits and traditions that nudge scientists in particular fields toward particular practices, problems, solutions.

Scientists need a paradigm to make progress, Kuhn emphasizes. A paradigm enforces constructive narrow-mindedness. Lacking a paradigm, science flails around wildly--like psychology since Freud fell out of fashion.

But Kuhn also bashes paradigms. He likens scientists under the thrall of a paradigm to drug addicts and the brainwashed subjects of Orwell’s 1984. Kuhn decrees that scientists can never say a theory is absolutely, objectively true; a theory is only “true” within the confines of the paradigm.

Bullshit. Scientists have discovered many objective truths. One of my favorites: the Milky Way is just one of zillions of galaxies populating the universe. And the light from other galaxies is red-shifted, which means the galaxies are hurtling away from us. Far out! [See “Comment from a Kuhnian” below.]

But this discovery emerged from a particular paradigm—a set of assumptions and practices in physics and astronomy--and it generated a new paradigm, the big bang theory. Science never unfolds in a vacuum, Kuhn’s right about that.

Okay, back to personal paradigms. Just as scientists need a paradigm to solve problems, so each of us needs a personal paradigm to get through life. You’re born with the rudiments of a personal paradigm encoded in your genes. That’s why you “know,” as an infant, how to suck your mother’s breast, return her smile with a smile, coo when she coos.

As you pass through adolescence into adulthood, you accumulate experiences, traumatic and ecstatic, and skills. You learn how to fish, solve quadratic equations, play hockey, roll a joint, flirt. You acquire biases, like a preference for Hendrix over Clapton. Your personal paradigm becomes hideously complex.

You can’t possibly be aware of it all, any more than you can track, say, the neural computations that underpin your decision to rewatch The Prisoner. Most of what we do, think, feel stems from processes unfolding down in the dank, dark cellar of our psyches. Freud was right about that.

Our personal paradigms help us solve big problems, like breeding and making a living, and small ones, like what to watch on TV tonight (Danger Man). But your personal paradigm exacts opportunity costs. It steers you toward certain life paths, away from others. It precludes you from seeing and being in other ways. You overlook anomalies, like the guy in the gorilla suit strolling through the room.

Kuhn says you can’t say one scientific paradigm is better than another, because there are no absolute standards for judging and comparing paradigms. Again, bullshit. Heliocentrism is better than geocentrism, the big bang theory is better than the steady-state theory.

But can you say one personal paradigm is better—in the sense of being more accurate--than another? My personal paradigm insists Trump is bad. But is that an absolute, objective truth, that Trump is bad? I see three options:

1, Yes, Trump is bad, objectively. And being a woke, bleeding-heart liberal is better, objectively, than being, say, a white supremacist. Some personal paradigms are definitely better than others.

2, No, you can’t say Trump is bad, because there are no absolute moral truths, only principles we cling to as axiomatic. One of my axioms says blowing up kids is bad, but Obama did it.

3, Oh hell, I don’t know. I suspect a godlike being, who sees everything against the backdrop of eternity, regards all our goodness and badness, suffering and kindness, cruelty and moral agonizing as laughably inconsequential.

I’m only dimly aware of my personal paradigm. And yet it informs—I hate to say determines--all my actions, related to career, love and so on. It shapes my dreams when I’m sleeping and my perceptions and decisions when I’m awake. It makes me email an old girlfriend, go to a wacky conference, write this column.

Normally, if life is going well, you don’t question your paradigm, you take it for granted. But at times—well, I’ll just speak for myself. My personal paradigm has begun to feel increasingly burdensome. It’s this thing I lug around with me, it weighs on me, like Delmore Schwartz’s “heavy bear.”

I dream of shedding this burden, escaping my personal paradigm, so I see Truth, Reality, God, The Weirdness. Whatever. To the extent that I believe in mystical enlightenment, the goal of Buddhism and other spiritual paths, this is how I imagine it: seeing what is, unfiltered.

What’s funny is that this fantasy stems from my personal paradigm. It dates back to my adolescence, when I read guys like Ram Dass, Alan Watts and Aldous Huxley. They persuaded me that meditation or mescaline could help me escape the cave into, well, something fabulous. Akin to lying on a balmy beach, watching the waves roll in, zephyrs of eternity ruffling my hair.

What’s also funny is that part of me—a sensible part—doubts whether raw, unfiltered perception is possible. And if it’s possible, maybe it’s not so fabulous. Maybe if some cataclysm sheers away your personal paradigm, you’ll feel naked, unsheltered, at the mercy of the world’s savage strangeness.

Maybe living without a personal paradigm would be like stumbling across a post-nuclear wasteland, devoid of hot showers and internet service. No flicking your iPhone to get fried chicken delivered to your door. No lying on a bed with a friend, holding her hand, chuckling at an episode of Frasier.

Maybe if your personal paradigm vanishes, you find yourself in hell, not heaven. A permanent bad trip. Like tumbling inside the severed ear in Lynch’s Blue Velvet.

And so I lie here in the dark at 2 AM, once again, sealed within the cell of my personal paradigm, fantasizing, and fearing, that it will vanish.

Oh, and the correct answer is Option1. I mean, obviously.

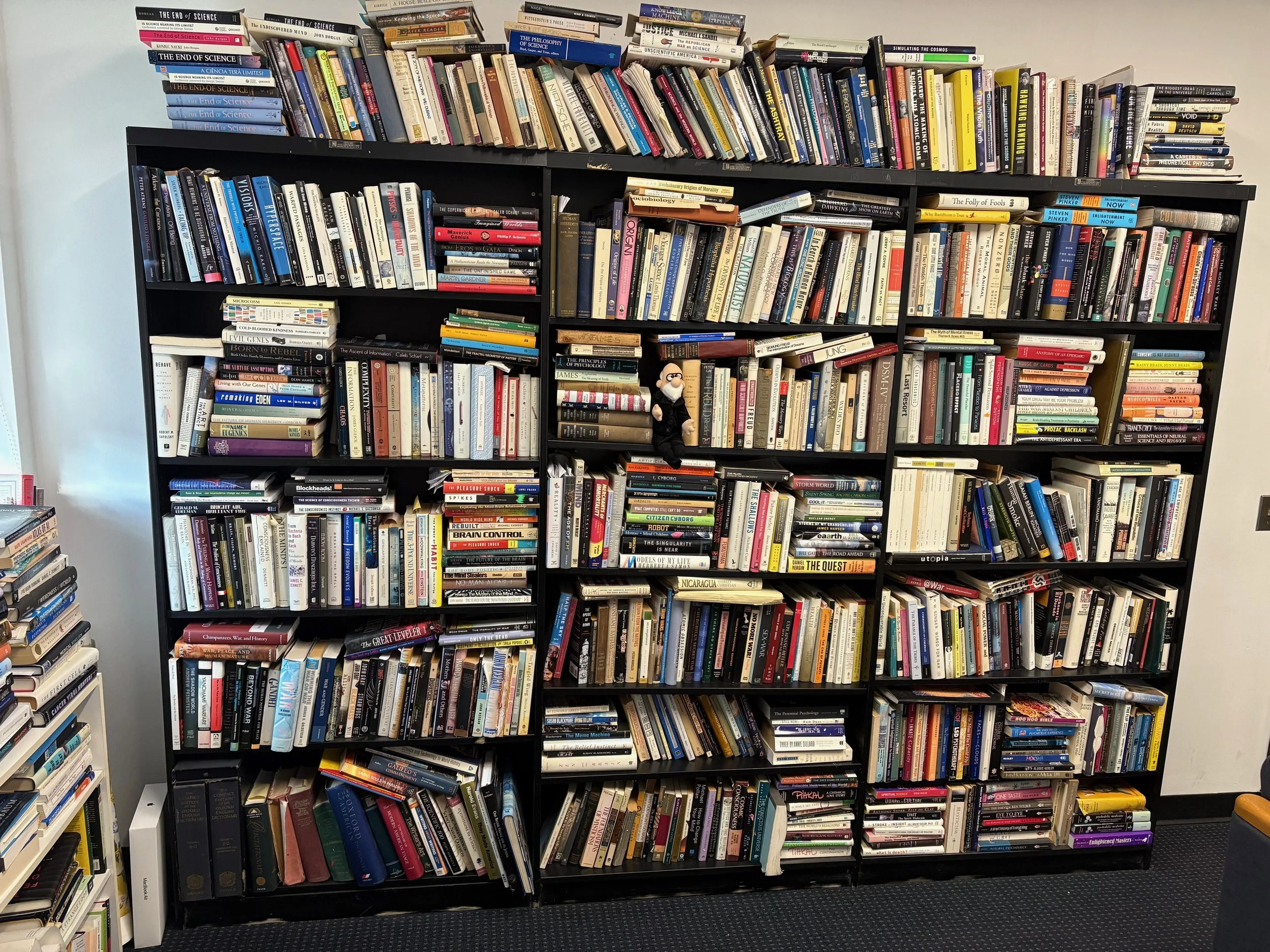

This is the actual bookcase in my office.

Further Reading:

Conservation of Ignorance: A New Law of Nature

The Dark Matter Inside Our Heads

Thomas Kuhn’s Skepticism Went Too Far

Entropy, Meaninglessness and Miracles

See also my book Rational Mysticism.

A Kuhnian comment: The esteemed historian Jim McClellen, who studied under Kuhn and was permanently infected by his philosophy, emailed me the following:

Dear John,

Like the good lapsed Catholic that you are, you can’t escape a burning desire for the true faith. In your present incarnation, that’s the “truth” of science. I had thought you had made good progress in admitting that we are always prisoners of our language and social context…that the holy grail of some bit of fixed knowledge of nature is always just outside our grasp…that we must be content with the notion that the stories we tell today about nature are better stories than the ones we told yesterday. But, alas, you backslide.

Hmm, what about those galaxies you claim as one of the many objective truths of science? I daresay that what Edwin Hubble thought he discovered in the 1920s isn't exactly what you conjure up as a galaxy in your mind today. Didn’t the recognition of the Big Bang recontextualize and thus change what we think of when we think of galaxies? How about Vera Rubin’s discovery of dark matter now holding galaxies together? Are these the same galaxies as before? Or, have our stories simply changed for the better? How about all those deep space images from the Webb and Hubble telescopes showing gazillion upon gazillions of galaxies racing around out there across the inconceivable vastness of time and space (as we presently conceive of them, of course; you’ll permit me a bit of literary license)? Doesn’t that stupendous census subtly shift what we mean by the term, galaxy?

Don’t get me wrong. I liked your piece and its evocation of the complex character of the self as it evolves over time, but believe me, your heliocentrism is hardly the same as Copernicus’ or even Newton’s for that matter. And that’s not bullshit!

Big hugs, Jim