My Secret Affinity for Many Worlds

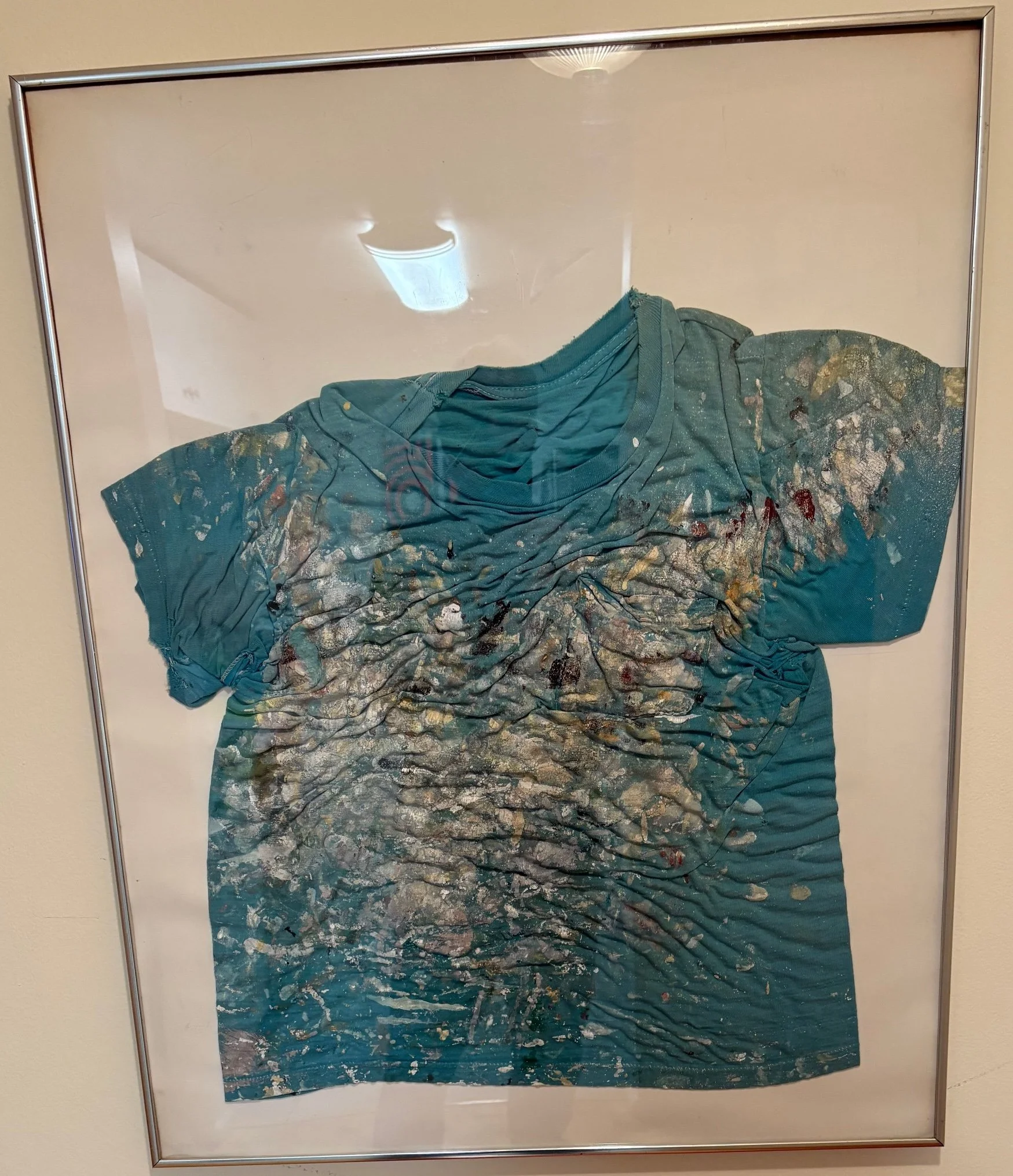

This is a shirt I wore while painting houses in Denver in the late 1970s. Maybe in another world I never left Denver.

HOBOKEN, OCTOBER 12, 2025. I’ve been feeling guilty about my last column, which reports on a shindig called Rat Fest, whose attendees adhere to an outlook called critical rationalism. I gripe about all the talks on the many-worlds interpretation, which I’ve denounced as “bullshit.”

What I fail to mention is that deep down, in my gut, or some fissure of my brain, I suspect many worlds is true. I confessed as much to a young man I met at Rat Fest, can’t remember his name.

Hugh Everett III invented many worlds in the late 1950s to explain away a puzzling feature of quantum mechanics. The wave function describes an electron, say, following many different possible paths. When you look at the electron, you find it following just one of those paths.

Everett proposed that the electron follows all those possible paths—in different worlds, or universes, branching off ours. Many worlds has prominent boosters, notably physicist David Deutsch, whom Rat Festers revere.

Physicist Sean Carroll, another many-worlds advocate, has estimated how many universes have branched off ours since the big bang: 2 to the power of 10 to the power of 112. That’s a lot of universes. Oh, and Carroll did that calculation more than six years ago, so there are even more universes now.

For years I’ve complained that many worlds is unscientific, because there’s no evidence for the alleged other worlds. And, come on, zillions of universes are branching off ours right… now? And… now? Give me a break. Plus, speculation about hypothetical worlds distracts us from the all-too-real problems of our world.

That’s what my critical, rational self tells me. But another self has long suspected that maybe there’s something to many worlds. I first encountered Everett’s theory in the early 1980s in some pop-physics book or article, and it got under my skin.

The theory inspired a short story I wrote in 1982, which I just dug out of my files. In the story, which I titled “New Wave Moral Fiction,” a narrator walks across Central Park to meet a woman. Here’s an excerpt:

I feel myself proliferating. Ghost selves peel off from me on their own private missions. One pivots and retraces my steps, returning to my apartment. One stops on the bridge and leans on the railing, watching the boats drift and turn, listening to the human murmur, the squeak of oars. One runs howling through the Brambles, darting after squirrels, tearing branches off trees and pounding them on stones. This continues as I enter the upper east side. Alter egos flit away from me, hurtling through store windows, leaping in front of cabs. When she opens the door to me, I know what the others are doing. One stands before her, unsmiling. One runs back down the stairs. One forces her to the floor, clamps his hand over her mouth, and whispers in her ear, “You, you, you.”

I wrote this story in the aftermath of a drug trip that loosened my grip on consensual reality. My story isn’t just a story, it describes my eerie intuition of ghost selves veering away from me into ghost worlds.

That sensation still seizes me now and then, usually when my brain, against my will, flashes back to brushes with death. I had two especially close calls during a month I spent in Nicaragua in 1985.

The first happened when I was hitchhiking from Esteli to the Pacific and got picked up by a drunken Sandinista soldier. We were speeding down an unlit blacktop through pouring rain when we crashed into a truck that had broken down in the middle of the road. I walked away covered in glass shards but unhurt.

A few days later I went bodysurfing in the Pacific and got caught in a vicious undertow. I dragged myself up on the empty beach and vomited sea water. Only then did I spot a sign showing a skull and crossbones and a big X crossing out a cartoon swimmer. Ah, so that’s why no one else is on this beach. What a dumb ass.

Not to mention the times in my late teens and early twenties when I drove like a maniac, drunk, with no consequence. Remembering these episodes, I don’t feel lucky, I feel creeped-out, my whole body winces. I envision my life-path as a highway with off-ramps branching away to dead ends.

Maybe there’s a personalized anthropic principle at work here. How have I lived so long? Why am I still here? You’d think the odds would have caught up to me by now. But if I’d died, I wouldn’t be here wondering why I’m here, would I?

Those off-ramps don’t have to be dead ends. They could lead to alternate lives. I don’t move from Denver to New York in 1980 to finish college. I don’t go to graduate school, become a science writer, get married, have kids, get my job at Stevens, get divorced. I don’t take a train to Philly to check out Rat Fest, which inspired me to write this column

My ghost lives haunt me. I feel them tugging at me, exerting a spooky quantum interference. Maybe those lives are real, and my life, this life, is the ghost life.

No, these thoughts are clearly irrational, a pathological side effect of my free-will function. Many worlds is pseudoscientific bullshit. This is my one and only life. So I tell myself.

Further Reading:

The Ironic Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics

Can Physics Ease the Sting of Death?

Multiverses Are Pseudoscientific Bullshit

The Infinite Optimism of David Deutsch

See also my free online book My Quantum Experiment.