Free Will and ChatGPT-Me

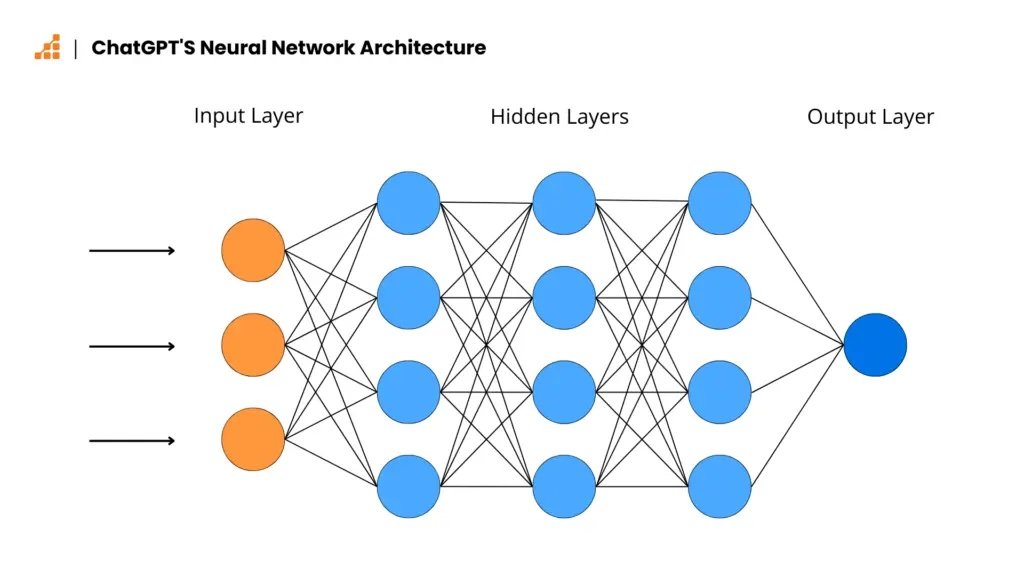

This neural network lacks free will, and so, I fear, do I. I found this image here.

November 16, 2023. I’ve aggressively defended free will lately. Writing, I argue here and here, exemplifies the conscious deliberations and decisions that constitute free will. But in the dead of night, hell, in the cold glare of morning, I fear I have no more free will than a mindless machine-learning program like ChatGPT.

ChatGPT’s programming, AI expert/critic Erik Larson points out, comes down to simple induction: feed it a prompt, and ChatGPT responds based on responses to similar prompts in its database of human chitchat. ChatGPT is a souped-up version of the software that finishes your text based on your past texts. It mimics human understanding, but it isn’t really intelligent, let alone creative; it doesn’t know what prompts or its responses to them mean.

This critique could apply to me, too. What am I but a program that reflexively turns prompts into all-too-predictable responses based on my prior experiences? My program is grounded in brain cells rather than silicon wafers, but so what? A hockey stick is a hockey stick whether it’s made of wood or aluminum.

The more I dwell on the analogy between me and ChatGPT, the more compelling it becomes. My brain, or mind (and what is the difference, really?), is a program that generates columns in the style of John Horgan. Call it ChatGPT-Me. This program isn’t really intelligent, let alone creative. And free will? Forget about it.

ChatGPT, you might argue, doesn’t have feelings, as you and I do. But even our most virtuous feelings are just algorithms in disguise. Evolutionary theorist Robert Trivers helped me grok this dark truth. Natural selection, he theorizes, programmed us to pity victims of injustice and to loathe the unjust, because these emotions helped our ancestors reproduce.

If you see a girl maimed by a bomb, you feel compelled to get her to a hospital—or, in my case, to write a column expressing pity for her and outrage toward the bombers. You don’t consciously calculate that your compassion and anger will be rewarded in ways that boost your chances of reproductive success. Natural selection has, in effect, made that calculation for you over millennia of evolution, and that’s why it predisposed you to feel pity and outrage in certain situations.

Yes, even our most sincere moral sentiments, from a Darwinian perspective, appear to be virtue-signaling underpinned by selfish genes. ChatGPT-Me can generate virtuous signals in its sleep.

Once I start thinking of myself as a machine for turning prompts into paragraphs, it’s hard to stop. I’m not sure where ChatGPT-Me ends and I begin. Do I even have a true self, capable of genuine choices, or am I inseparable from ChatGPT-Me?

I am reminded of “Borges and I,” the creepy little confession of Argentinian fabulist Jorge Luis Borges. The narrator, who presents himself as the real, authentic Borges, discloses his struggle to maintain his independence from his oppressive public persona, “Borges.” “Borges” shares the narrator’s fondness for hourglasses, maps and the prose of Robert Louis Stevenson, “but in a vain way that turns them into the attributes of an actor.”

When the narrator tries to re-invent himself by writing in a new style, “Borges” instantly co-opts this new behavior. The narrator concludes: “Thus my life is a flight, and I lose everything and everything belongs to oblivion, or to him. I do not know which of us has written this page.”

I am writing this column, I suppose it’s all too obvious, to try to assert my independence from ChatGPT-Me, the inductive machine inside my brain. ChatGPT-Me couldn’t write a column like this, which casts doubt on free will! Or could it? ChatGPT-Me is familiar with my fondness for Borges and hatred of war, my proneness toward derealization and ironic self-deprecation, my annoying tendency to make assertions and take them back.

I don’t know who is writing this sentence.

Further Reading:

Free Will and the Sapolsky Paradox

Free Will and the Could-You-Have-Chosen-Otherwise Gambit

Can a Chatbot Be Aware That It’s Not Aware?

Cutting Through the ChatGPT Hype

How AI Moguls Are Like Mobsters

See my recent chat with free-will-denier Robert Sapolsky here.

See my recent chat with ChatGPT critic Erik Larson here.

I profile Robert Trivers in my free online book Mind-Body Problems.