The “Scandal” Behind the Biggest Study of Antidepressants Ever

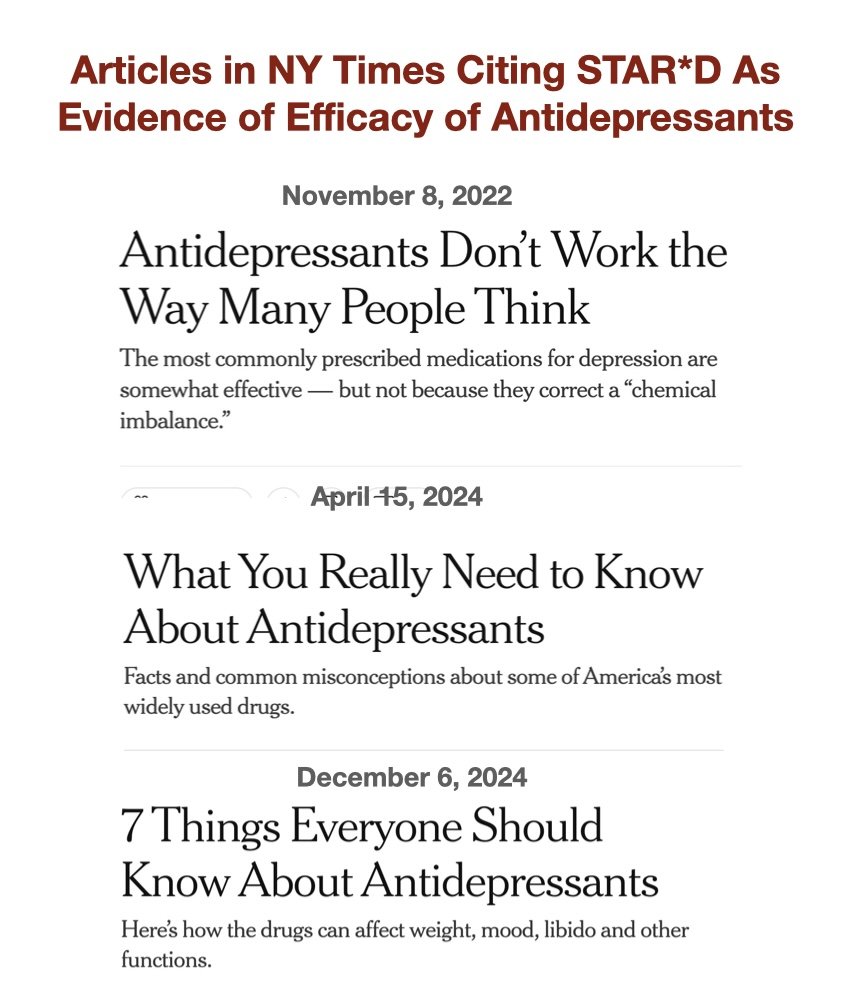

In these stories The NY Times cites the flawed STAR*D study as evidence that antidepressants help “nearly 70 percent of people.” The webzine Mad In American posted this graphic in a recent article on the STAR*D “scandal.”

HOBOKEN, MARCH 8, 2025. Do antidepressants work? Yes, they do, for more than two out of three patients, or so The New York Times assures us. In a February column, “7 Things Everyone Should Know About Antidepressants,” The Times reports:

“A large study of multiple antidepressants found that half of the participants had improved after using either the first or second medication that they tried, and nearly 70 percent of people had become symptom-free by the fourth antidepressant.”

That “nearly 70 percent” figure has been cited by The NY Times and other media, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and psychiatry textbooks. But that figure is grossly inflated. According to one count, only 3 percent of the participants in the “large study,” which is known as STAR*D, got well and stayed well. Here’s the backstory:

Prescriptions of antidepressants have surged for decades in spite of persistent doubts about the medications’ benefits and concerns about side effects. Antidepressant trials typically examine how patients respond to a single drug over an 8-week period; the medication is compared to an inert substance, or placebo.

Some meta-analyses indicate that antidepressants are scarcely more effective than placebos. Defenders of antidepressants claim these meta-analyses do not reflect the medications’ true benefits, which emerge when physicians keep prescribing different antidepressants until they find one that works.

To test this claim, more than two decades ago the NIMH carried out the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial, STAR*D. The NIMH calls STAR*D “the largest and longest study ever conducted to evaluate depression treatment.”

The study involved 23 mental-health centers and 4,041 patients ages 18-75 diagnosed with depression. STAR*D’s design was complex. First, patients were given the antidepressant Celexa for 12 weeks. Patients who were not in remission, symptom-free, at the end of that 12-week treatment were given up to three subsequent alternative treatments, each also lasting 12 weeks, involving different medications. Patients in remission at the end of each treatment remained on that treatment (sometimes with modifications) and were monitored for a year.

In 2006 STAR*D researchers reported in Psychiatry Online that 36 percent of patients were in remission after 12 weeks on Celexa; more patients responded positively to each subsequent 12-week round of treatment, leading to a cumulative remission rate of 67 percent, or “nearly 70 percent.”

But the STAR*D researchers got these great results because they improperly switched their protocols for evaluating patients’ depression and accounting for patients who dropped out of the study. Or so psychologist Edmund Pigott and others assert in a 2023 report in the British Medical Journal, BMJ. Pigott’s group calculates that, if STAR*D’s original protocols are correctly applied, only 35 percent of patients—not 67 percent—achieved remission.

The STAR*D researchers dismissed this critique. But in Psychiatric Times, psychiatrists Nicholas Badre and Jason Compton agree with the analysis of Pigott et al. Badre and Compton point out, for example, that STAR*D researchers failed to exclude 607 patients who—before the study began--had no symptoms or symptoms so mild that they were “not appropriate for a clinical trial.”

Badre and Compton conclude: “Our patients, our field, and our integrity demand a better explanation of what happened in STAR*D than what has thus been provided. Short of this, the best remaining course to take is a retraction.”

For a scathing recap of the STAR*D saga, see also this article on MadInAmerica.com by the webzine’s founder, journalist Robert Whitaker. For decades, Whitaker has reported on the limits of drug-based approaches to mental illness; see my recent Q&A with him here.

Whitaker highlights a startling statistic uncovered by Pigott and others in 2010: Of the 4,041 patients originally enrolled in STAR*D, only 108 “remitted and then stayed well and in the study to its one-year end, a documented stay-well rate of 3%. All of the others had either never remitted, remitted and then relapsed, or dropped out of the study.” In light of this 3-percent statistic, even the 35-percent success rate attributed to STAR*D in 2023 by Pigott’s group is generous.

Whitaker accuses STAR*D’s authors of conflicts of interest. The authors, he notes, “listed a collective total of 151 ties to pharmaceutical companies. Eight of the 12 had ties to Forest, the maker of Celexa, the study drug given in the first stage of the study.” Whitaker faults The NY Times and other major media for ignoring the STAR*D “scandal.”

Meanwhile, prescriptions for antidepressants in the U.S. keep rising. A 2020 CDC study estimates that between 2009 and 2018, the percentage of adults taking antidepressants grew from 10.6 percent to 13.8 percent. During the Covid pandemic, prescriptions for teens and young adults rose by 63.5 percent, according to a 2024 report; the increase for girls ages 12-17 was 129.6 percent.

This growth is driven in part by “telehealth services,” in which physicians provide online consultations. The website Hims.com says you can get a prescription for psychiatric medication mailed to you merely by filling out an online assessment that takes “about 10 minutes.”

A final, unavoidable note: If you criticize psychiatry, you risk being lumped together with the Scientology cult and Robert Kennedy. I fear Kennedy will be a disastrous Health Secretary. I hope his ham-handed attacks on psychiatric medications do not discredit the work of informed, meticulous critics like Whitaker and Pigott and make a bad situation worse.

Further Reading:

See my Q&A with Robert Whitaker: The Drug-Based Approach to Mental Illness Has Failed. What Are Alternatives?, and check out Whitaker’s book Anatomy of an Illness and webzine Mad in America.

I delve into treatments for mental illness in “The Meaning of Madness,” chapter five of my book Mind-Body Problems. See also my columns Why Freud Still Isn’t Dead and Psychiatry Is Broken. Can It Fix Itself?