Jack London, Liberal Arts and the Dream of Total Knowledge

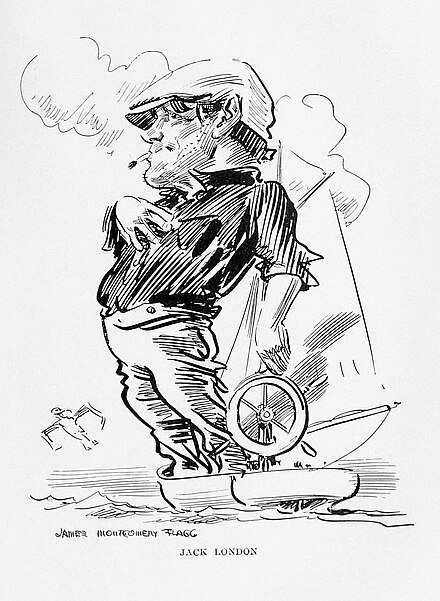

Jack London’s fictional doppelganger Martin Eden reads because he wants to see the “kinship” between even the most seemingly incongruous things, from murder to fulcrums. Yeah, me too, but is such a unified vision feasible? I found this cartoon of London on Wikipedia.

HOBOKEN, JULY 2, 2024. Most defenses of liberal arts education strike me as whiny drivel. But “Do Liberal Arts Liberate?”, an essay in Nautilus by Nick Romeo, made me go, Yes, that’s it!

Romeo, a professor of journalism, dwells on Jack London’s novel Martin Eden, published in 1909. Like London, Martin Eden is an uncouth, hard-drinking sailor who, after falling in love with a rich college girl, becomes mortified by his ignorance. He starts haunting libraries, Romeo writes, “devouring books on algebra, history, sociology, physics and poetry.”

Essentially, Martin is giving himself a liberal arts education. His original goal is becoming worthy of his hoity-toity girlfriend and eligible for a decent white-collar job. But then, in part because of his self-education, Martin’s motivation deepens. Here is how London puts it:

[Martin] drew up lists of the most incongruous things and was unhappy until he succeeded in establishing kinship between them all--kinship between love, poetry, earthquake, fire, rattlesnakes, rainbows, precious gems, monstrosities, sunsets, the roaring of lions, illuminating gas, cannibalism, beauty, murder, lovers, fulcrums, and tobacco. Thus, he unified the universe and held it up and looked at it, or wandered through its byways and alleys and jungles … observing and charting and becoming familiar with all there was to know.

I love that riff! That’s what provoked my Yes, that’s it! I’m the product of a classic liberal-arts education. I majored in literature while also taking classes in history, philosophy, math, science, the works. Why? I wanted to impress people, especially potential mates and employers, with how clever I am.

But like Martin Eden, I also hoped to become “familiar” with all the odds and ends of the world and with all our responses to it, from calculus to stream-of-consciousness fiction. Yup, I wanted to know everything and see how it all fits together. Unity of knowledge, baby!

I’m still chasing this goal, even though I know it’s nutty. The terrible paradox is that the more you know, the more you realize how little you know—as that old grouch Socrates warned 2,400 years ago.

Plus, our hyperactive culture keeps churning out new stuff to puzzle over. In addition to rattlesnakes and fulcrums and other things on Martin Eden’s list, we now have information theory, LSD, drones, ChatGPT, climate change, Palestine, transgender surgery, multiverse theories…

My efforts to discern the “kinship” between things, the unity, often have the opposite effect. Example: Four years ago I set out to learn quantum mechanics, which Stephen Hawking and other bigshots assure us is the ultimate description of nature.

To get quantum mechanics, you must get linear algebra. So in the summer of 2020 I’m in my Hoboken apartment, struggling to multiply the boxes of numbers called matrices, when I hear a hubbub outside my building. I look out the window and see folks marching down Frank Sinatra Drive holding “Black Lives Matter” signs.

Oh, how my cognitive-dissonance alarms clanged! I thought, What the hell does quantum mechanics have to do with racial injustice? Or for that matter with the Covid epidemic sweeping the country? Or the cancer ravaging my friend Robert? Or all the other things I fret over on a typical day?

It’s easy to construct a consistent worldview if you omit what doesn’t fit. And physics omits a lot. Some scientists insist that science as a whole, if not physics specifically, can account for everything that matters. That’s the theme of biologist Edward Wilson’s 1998 bestseller Consilience.

Wilson contends that the sciences are “consilient” with each other, that is, consistent and even complementary. Physics explains chemistry explains biology explains psychology explains economics and so on. The scientific version of the great chain of being.

Wilson prophesies that we’ll all eventually see the arts and humanities, and even religion and mysticism, as consilient extensions of science. What’s funny is that physicists can’t even unify quantum mechanics and relativity. So what hope is there of unifying, say, quantum cosmology and queer theory?

Science has given us deep, unifying insights into nature: All matter is made of quarks and electrons. All living things are descended from a common ancestor. But these revelations don’t help us cope with the shit that ordinary life throws at us. Injustice, heartbreak, death.

The arts and humanities don’t necessarily help us cope, either. Plato and Aristotle assured us that knowledge-seeking makes us happier and more virtuous, but I see scant evidence for that claim. Let’s face it, the primary function of a liberal arts education, and higher education in general, is manufacturing workers to serve our capitalist overlords.

Martin Eden doesn’t end well. Martin becomes a successful writer, but he is estranged from his old working-class buddies and his wealthy lover, for whom culture is just a status symbol. Lonely and depressed, Martin drowns himself.

That’s a bit extreme. Like Martin, I’ve become cynical about the knowledge racket. And yet I still read articles and books on neuroscience and biology and yada yada. I read fiction, too, new and old. I even read poetry now and then! Why? What’s the point? It’s not money or mating opportunities or enlightenment, whatever that is.

I read for fun, for the hell of it. I like learning new things, even, especially, if they make me feel dumb, like linear algebra. And I like discovering how others see the world, even, especially, if their ideas clash with mine. Robert Sapolsky’s Determined makes me question my faith in free will, and that’s fine.

I guess what I’m saying is that I’ve come to value befuddlement and dissonance more than illumination and unification. If the dissonance overwhelms me, as it has been lately, I try to pay attention to what is right before me and to forget about everything else. As Emily Dickinson does in “A Bird, came down the Walk,” or as Chris Cornell does in “Doesn’t Remind Me”:

I like studying faces in the parking lot

'Cause it doesn't remind me of anything

I like driving backwards in the fog

'Cause it doesn't remind me of anything

If I’m lucky, for a moment I see nothing but a John-To-Go in all its glorious, infinitely improbable weirdness. Then, inevitably, that thing reminds me of other things, and I fall back into the cacophonous, fractious world.

Further Reading:

My Quantum Experiment is one long attempt to find “kinship” between physics and things that matter to me. See especially Chapter Four, “I Understand That I Can’t Understand.”

And here are some relevant columns:

The Delusion of Scientific Omniscience

Conservation of Ignorance: A New Law of Nature.

What’s the Point of the Humanities?

The Golden Bowl and the Combinatorial Explosion of Theories of Mind